by Pádraig Ó Méalóid

In 1977 Dial Press of New York published Robert Mayer’s first novel, Superfolks. It was, amongst other things, a story of a middle-aged man coming to terms with his life, an enormous collection of 1970s pop-culture references, some now lost to the mists of time, and a satire on certain aspects of the comic superhero, but would probably be largely unheard of these days if it wasn’t for the fact that it is regularly mentioned for its supposed influence on a young Alan Moore and his work, particularly on Watchmen, Marvelman, and his Superman story, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? There’s also a suggestion that it had an influence on his proposal to DC Comics for the unpublished cross-company ‘event,’ Twilight of the Superheroes. But who’s saying these things, what are they saying, and is any of it actually true?

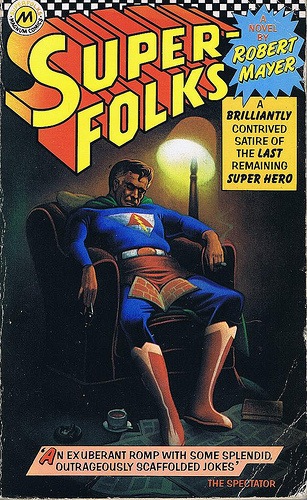

Before I get to any of that, though, here’s a brief(ish) overview of the book, just so I can refer back to it as I’m going along, if I need to. Superfolks was first published by Dial Press in the US in 1977, and was subsequently published in the UK by Angus & Robertson in hardback in 1978, and it then by Magnum Books in paperback in 1980, so it was at least potentially available in Northampton in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Alan Moore was, and remains, a voracious and omnivorous reader, and a book about comic characters would almost certainly have been something he would have wanted to have a look at, so it could have been – and as we shall see later, actually was – read by a young Moore at that time. But did the contents of that book influence him to such an extent that all of his major superhero work was based on it? Here, I’m afraid, is where I’m going to give away all the big secrets of the book, such as they are. If you don’t want to know, then go away, read the book, and meet us all back here afterwards…

David Brinkley is a forty-two year old New York journalist. He also has a secret: he’s a super-hero. He’s originally from the planet Cronk, where he was known as Rodney, the baby son of Archie and Edith, who put him into a spaceship (as Cronk was just about to explode) and send him to Earth, where he was found by a couple called Franklin and Eleanor from Littletown, who adopted him. He went to Middletown High, where he was infatuated with a girl called Lorna Doone. As an adult, he was originally involved with a fellow journalist, Peggy Poole, before he met his wife, Pamela Pileggi. (To add to these two sets of PP initials, we’re also told that ‘The world is actually ruled by a shadowy, rarely seen Dallas multi-billionaire midget called Powell Pugh.’ Peter Pan is in there as well, as a very dissolute version of himself.)

Brinkley is six foot one and has blue hair. His costume is described as a skin-tight blue leotard, with his emblem in white on the chest; slim red boots; red overshorts; a white cape; and a purple mask. He was known as The Man of Iron, and The Man of Tomorrow. His roster of enemies had names like Hydrox, Oreo, Univac, Elastic Man, Logar the mad scientist, and Pxyzsyzygy, the elf from the Fifth Dimension. Because he’s from Cronk, he is of course vulnerable to Cronkite, the radioactive meteoric remains of that planet. We’re never actually told what Brinkley’s superhero name is: he’s referred to as Indigo, but it’s made clear that this isn’t his actual name, but a codename – at one point, however, someone talking about him gets the first syllable ‘Supe-’ out before choking on their food, so we can interpret that as we choose. We’re also never told what the white emblem on his chest is, incidentally.

When the book starts, Brinkley has been retired from superheroing for eight years, because his powers were starting to fail on him. However, rioting, looting, and general lawlessness has broken out in New York, and the police force has resigned after not being paid for two months, following the bankruptcy of New York (which very nearly actually happened), so he decides that he’d better make a comeback to help deal with it. We’ve already been told that Batman and Robin, Superman, and the Marvel Family are all dead, so he tries to recruit Captain Mantra, another superhero who has given it all up. Mantra, under his other identity of Billy Buttons (and if Indigo is Superman, then Captain Mantra is very definitely Captain Marvel), is in a sanatorium, ever since seeing his twin sister Mary cut to pieces by a train when Dr. Spock tied her to the railroad tracks and she couldn’t remove her gag in time to say her magic word. Buttons could change back into Captain Mantra, but has sworn never to do so again, so Brinkley seem to be on his own.

So, to run through the rest of it quickly, it turns out there are several different parties who want Brinkley’s superhero alter ego out of the way, and have staged the riots to flush him out: the aforementioned multi-billionaire midget, Powell Pugh; the Mafia; the Russians; and of course the CIA – they’re all working towards the same goal, but it’s never made completely clear to what extent each interacts with the other, except that Powell Pugh seems to be in the centre of it all.. There is a very brief appearance by a supervillain called Demoniac, who is the offspring of an incestuous coupling between Billy and Mary Mantra, but he’s dead within a few pages. In the end, we find out that Powell Pugh is actually Pxyzsyzygy, the elf from the Fifth Dimension, and that, through all the companies he owns, he has been introducing tiny amounts of Cronkite into pretty much all manufactured items, explaining why Brinkley’s powers were fading. However, because he’s been caught, Pxyzsyzygy has to return to the Fifth Dimension. Brinkley has to choose between leaving Earth froever, which will mean he’ll have full use of his powers, or remaining with his family, and never having super-powers again. He does the right thing, and stays on Earth. Oh, and it turns out that everyone knew he was Indigo all along – after all, who else had blue hair?

Besides all of that, the book is filled with references to people who would have been famous in the mid-seventies, but not so much so now. For instance – and something I didn’t know until I decided to look it up, just in case – there was an actual American newscaster called David Brinkley. And, if you haven’t heard of Walter Cronkite, another American newscaster – although his fame had even reached as far as me, here in Ireland – then the fact that Brinkley is from the planet Cronk is not going to be as funny as the author wanted it to be. There are any number of other examples of actual people getting walk-on parts: actress Marilyn Monroe is a nurse, leading feminist Bella Abzug is a taxi driver, dancer Fred Astaire is the President’s valet, and so on, and so on. Other, non-real, characters also get a mention: on the first page we’re told Snoopy is dead, killed by the Red Baron, although he turns up alive later on. And the reference to Lorna Doone is more likely to refer to the American brand of shortbread biscuits than to the English novel by RD Blackmore. At one point, during the really-quite-serious bit at the end, where Brinkley is trying to decide whether to stay on Earth or go away forever, Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother appears, says a few lines, and goes away again, for no reason that I can make out – it’s certainly not to advance the plot, or any other legitimate literary device I can think of. And this is part of the problem I have with Superfolks – the thing is, as far as I’m concerned, it’s really not very good. It reads, more than anything else, like one of those bad first novels that authors have in the desks, never to see the light of day. It cannot make up its mind, from page to page and sometimes from sentence to sentence, whether it’s attempting to be serious, humorous, cynical, flippant, or something else. Kirkus Reviews seem to agree, in this review, which says, ‘Mayer should include a laugh-track with every copy, since readers unwilling to give stock responses to TV images will find this about as funny as a plastic taco.’ The book would probably have benefitted hugely from being put into the hands of a good editor, who might have actually cleared a lot of this up, and made it into the better piece of work that is undoubtedly in there, struggling to get out. Still, what we’ve got is what we’ve got…

So, anyway, that’s the book itself. The next thing is, where and when did these suggestions that Alan Moore had ransacked the book appear, and who was saying them?

The first mention of this I can find is from Grant Morrison, who had a column called Drivel in the British comics magazine Speakeasy (ACME Press, UK) between September 1989 and March 1991, around the same time as he was breaking into US comics with Animal Man and Arkham Asylum. Right in the middle of his run, in Speakeasy #111 (July 1990), his column included this:

Cor, What a Coincidence!

Why, just the other day I was hanging around outside Saxone, hoping for a sniff of those new brogues, when up come a fella with a copy of this old book called Super-Folks by Robert Mayer in his hand. I’d heard of it but hadn’t read it. So home I skipped and buried my nose deep within the pages of this remaindered treasure.

And what a read it was! It starts off with this brilliant quote from Friedrich Nietzsche, right? ‘Behold I teach you the Superman: he is this lightning he is this madness!’

Then it really gets going!

It’s all about this middle-aged man who used to be a superhero like Superman. There’s a weird conspiracy involving various oddly-named corporate subsidies. There’s a simmering plot to murder the Superman guy and unleash unknown horrors on the world. There’s another middle-aged character in a rest home, who’s vowed never again to say the magic word that transforms him into Captain Mantra. There’s a corrupted and demonic Captain Mantra Junior and loads of other stuff about what it would be like if superheroes were actually real. In the end, the villain turns out to be a fifth-dimensional imp called Pxyzsyzgy, who has decided to be totally evil instead of mischievous.

Let me tell you, it’s a book I can only describe as visionary, and you must also believe me when I say it would make a great comic.

Or even three great comics.

If only I’d read this book in 1978, I might have made something of my life and avoided all this pompous, pretentious Batman nonsense that’s made me a laughing-stock the world over.

Oh well, never mind. There are plenty more books on the shelves.

After that, there’s a short final piece where Morrison writes:

That Bit at the EndAll of a sudden, I’ve got the most terrible headache. It’s one of those nasty spite headaches, and I’ve no-one but myself to blame. I’ve over-indulged in the lowest form of wit this month, and it’s time to turn over a new leaf.

Or is it?

It’s fairly obvious that Morrison is pointing the finger at Alan Moore, and specifically at, as he says, ‘three great comics’: Marvelman (‘this middle-aged man who used to be a superhero like Superman’), Watchmen (‘a weird conspiracy involving various oddly-named corporate subsidies’), and Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (‘a simmering plot to murder the Superman guy and unleash unknown horrors on the world’).

One big influence on Moore seems to have been the satirical novel Superfolks by Robert Mayer (1977), about a Superman-like hero who has retired, grown fat and become increasingly impotent in any number of ways. Moore’s work echoes the book in a number of places: the idea of Superman giving it all up to live a normal life has been a recurring theme; the police going on strike because the superheroes are stealing their jobs is a key plot point in Watchmen; also, Superfolks and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? have the same ending – a formerly mischievous but now truly evil pixie character is behind the events of both.

Although Superfolks was first published in 1977, and had become slowly better known as the years went by, it still took until December 2003 for it to be republished in the US. Nat Gertler of About Comics of Camarillo, California, got the rights for a limited edition of 2000 copies, which were only made available in direct market comics shops, according to his website. I can’t help but notice that the real David Brinkley died in June 2003, six months before this edition came out. Whether there is any correlation between this long gap in publication and that fact, I honestly don’t know, although, as Sherlock Holmes might say, it is strangely suggestive. The About Comics edition came with a cover illustration by Dave Gibbons, and an introduction by comics writer Kurt Busiek, who was effusive in his praise of the book, and in his opinion of its significance. Amongst other things, he says:

This is the best Superman parody I’ve ever read. […] It was clearly written by a guy who knows and likes these characters, who knows the foibles of the superhero genre, and embraces them in all their absurdity.

This is one of the best Superman stories I’ve ever read. […] there’s a damn solid plot, a story that – if it actually was a Superman story […] would be well-remembered by fans for its clever ideas, its emotional power and its scope.

This is one of the best superhero stories I’ve ever read. Here, the superhero isn’t a metaphor for power, but a metaphor for power slipping away. This man’s a grownup – aging, fading – and the story is all about that.

I’m not the only one, either. Find the people who did new and different things with superhero stories, and odds are you’ll find that they’ve read and been affected by this book. Ask Mark Waid about it, and watch him smile at the thought of it. Ask Neil Gaiman, watch his eyes light up with enthusiasm as he talks about what an impact it had. Ask Grant Morrison. Look at the work of Alan Moore, possibly the most significant creator the field currently has of superhero stories that break with formula and expectation and inspire others to do the same and you’ll see this book’s influence throughout – from the epigraph that opens Superfolks and Watchmen being the same, from Kid Miracleman to Ozymandias’s pervasive and complex commercial empire to Mr. Myxyzptlk’s motivations and revelations in the finale of The Last Superman Story, and more.

I want to point out where Busiek says, ‘…from the epigraph that opens Superfolks and Watchmen being the same…’ He presumably meant to say Miracleman, rather than Watchmen.

I loved Superfolks — it was a revelation to me when I read the book (with the gogochecks on the cover) and it was about stuff I knew, and taking it semi-seriously.

There is one final publication of Superfolks I want to mention, which contains another example of the finger being more-or-less pointed at Alan Moore. In March 2005 St. Martin’s Griffin of New York City published the book in paperback, and this remains the most recent edition of the book, to my knowledge. This time ‘round, the introduction was written by Grant Morrison, where he says, amongst other things,

Behind the unpromising pulp facade, I was happy to uncover some of the aboriginal roots nourishing the ’80s ‘adult’ superhero comic boom. […] In Superfolks I’d found a barely acknowledged contribution to the vivid and explosive evolution of the ‘mature’ superhero story that characterized the ’80s and ’90s. […] In his bittersweet portrayal of the middle-aged Captain Mantra, with that half-remembered magic word always hovering somewhere on the tip of his tongue, I could see that Robert Mayer had prefigured the era of so-called ‘deconstructionist’ superheroes, which in turn spawned many of the medium’s most memorable and ambitious works. In the conspiracy themes, complex twisting plot-lines, fifth-dimensional science, thrilling set pieces, and reverses of Superfolks, we can almost sniff the soil that grew so many of our favourite comics in the ’80s, ’90s, and beyond. […] Historians of the funnies will find in Superfolks a treasure trove of tropes. Everyone else gets a good laugh and a good story as Mayer takes us to a wonky Earth-Nil parallel universe of downtrodden urban supermen and clapped-out cartoons.

Originally, all the commentary was in books and magazines. However, with the advent of the digital age, we invariably find it spreading to the Internet. Robert Mayer, the author of Superfolks, eventually joined in the debate himself, on his website. He says,

Time was when superheroes resembled grown-up Boy Scouts in tights. They were clean-living, clean-thinking, all-American chaps or women without a neurosis, sexual hang-up or mean thought in sight, always fighting for justice, America and the little guy against the villains of their make-believe worlds.

Then came the 1980s – and all that changed. Superheroes became filled with inner darkness, psychological problems, insecurities. In other words, they became real, suffering humans with real hang-ups alongside their super powers. The Dark Knight, for example. Who is to blame for this dark, downward spiral into the superhero abyss? Apparently, I am.

And, in a piece no longer on his site, he also said,

Among the spawn, many critics say, were much of Alan Moore’s work, including the ‘classic’ Watchmen. To my knowledge Mr. Moore has never publicly acknowledged a debt to Superfolks, but you can Google Superfolks and read all about it.

The other thing the Internet gave us, of course, is any number of opinions about the relationship between Superfolks and the work of Alan Moore. You only have to type the words ‘Alan Moore,’ ‘stole,’ and ‘Superfolks’ into your search engine to find any number of posts on blogs and forums, stating that, as you might guess, Alan Moore stole all his ideas for Superfolks. A quick search of the Internet brings these two examples: Here, the book reviewer actually spends most of his time talking about Kurt Busiek’s introduction, and says,

According to the introduction, there’s a disturbing number of prominent comics writers today who read this book back in the 70’s and cite it as a primary influence on their work. In addition to Busiek, Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, and Mark Waid are all avowed Superfolks fans. Read this book, and you’ll find out where Moore swiped more than a few of his ideas for Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, Miracleman, and Watchmen.

…and here, posted just as I sit here typing, we see what is a very typical posting, in a thread about DC’s forthcoming Before Watchmen comics:

I wonder how Robert Mayer would feel to see how Moore has ripped off his Superfolks novel countless times without credit.

There is one other online article I want to look at before I get to the end of this part of the story. The last post on a blog called Flashmob Fridays, on the 24th of February 2012, looked at Alan Moore’s Twilight of the Superheroes proposal to DC Comics in 1987, which was never actually written and published, and remains one of his great lost works. The article is written by three different people, and one of them, Joseph Gualtieri, see in that proposal further evidence of Moore’s, as he says, ‘strip-mining’ of Superfolks for ideas.

Then there’s some of the content. Blackhawk picking up teenage boys is a gag (he’s really recruiting them into a private army), sure, but Moore also has Sandra Knight [Phantom Lady] sleeping around, Plastic Man as a gigolo, and an incestuous relationship between Billy and Mary Batson.

The other thing that occurred to me this time about Twilight is how in a lot of ways it’s the ultimate product of Moore’s decade of strip-mining Robert Mayer’s Superfolks that saw him produce Marvelman, Watchmen, and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? When Moore finally spoke publicly about Mayer’s book [a link which leads, embarrassingly but perhaps inevitably, top an interview I did with Moore where I asked him about this], he tried to minimize its role in his career and attack Grant Morrison for bringing it up (in a coded manner) in a magazine column:

I can’t even remember when I read it. It would probably have been before I wrote Marvelman, and it would have had the same kind of influence upon me as the much earlier – probably a bit early for Grant Morrison to have spotted it – Brian Patten’s poem, ‘Where Are You Now, Batman?’, […] I’d still say that Harvey Kurtzman’s Superduperman probably had the preliminary influence, but I do remember Superfolks and finding some bits of it in that same sort of vein.

The Twilight proposal may be the best example of just how untrue what Moore said is – he clearly internalized Superfolks to such a degree that he never, ever makes note of the fact that Mary and Billy Batson’s relationship is an incestuous one. For those unfamiliar with Superfolks, the coupling of the book’s Batson analogues is a key plot point, producing one of the book’s major villains. Meyer’s take on the Marvel Family hangs all over Moore’s take on Billy’s sexuality in the proposal.

And that’s the case for the prosecution. Specifically, this is what the various people I’ve quoted are saying that Alan Moore took from Superfolks:-

In 1990 Grant Morrison suggested that Moore ‘three great comics’ on the book: Marvelman (‘this middle-aged man who used to be a superhero like Superman’), Watchmen (‘a weird conspiracy involving various oddly-named corporate subsidies’), and Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (‘a simmering plot to murder the Superman guy and unleash unknown horrors on the world’).

Fifteen years later, in 2005, he was being a bit more circumspect in what he said, although it’s still pretty obvious that Moore was front and centre when he said: ‘In his bittersweet portrayal of the middle-aged Captain Mantra, with that half-remembered magic word always hovering somewhere on the tip of his tongue, I could see that Robert Mayer had prefigured the era of so-called ‘deconstructionist’ superheroes, which in turn spawned many of the medium’s most memorable and ambitious works. In the conspiracy themes, complex twisting plot-lines, fifth-dimensional science, thrilling set pieces, and reverses of Superfolks, we can almost sniff the soil that grew so many of our favourite comics in the ’80s, ’90s, and beyond. […] Historians of the funnies will find in Superfolks a treasure trove of tropes.’

In 2001 Lance Parkin said: ‘One big influence on Moore seems to have been the satirical novel Superfolks by Robert Mayer (1977), about a Superman-like hero who has retired, grown fat and become increasingly impotent in any number of ways. Moore’s work echoes the book in a number of places: the idea of Superman giving it all up to live a normal life has been a recurring theme; the police going on strike because the superheroes are stealing their jobs is a key plot point in Watchmen; also, Superfolks and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? have the same ending – a formerly mischievous but now truly evil pixie character is behind the events of both.’

In 2003 Kurt Busiek said: ‘Find the people who did new and different things with superhero stories, and odds are you’ll find that they’ve read and been affected by this book. […] Look at the work of Alan Moore, possibly the most significant creator the field currently has of superhero stories that break with formula and expectation and inspire others to do the same and you’ll see this book’s influence throughout – from the epigraph that opens Superfolks and [Miracleman] being the same, from Kid Miracleman to Ozymandias’s pervasive and complex commercial empire to Mr. Myxyzptlk’s motivations and revelations in the finale of The Last Superman Story, and more.’

And up until recently Robert Mayer’s own website said: ‘Among the spawn [of Superfolks], many critics say, were much of Alan Moore’s work, including the ‘classic’ Watchmen. To my knowledge Mr. Moore has never publicly acknowledged a debt to Superfolks, but you can Google Superfolks and read all about it.’

Finally, in 20012 Joseph Gualtieri said: ‘[Moore] clearly internalized Superfolks to such a degree that he never, ever makes note of the fact that Mary and Billy Batson’s relationship is an incestuous one. For those unfamiliar with Superfolks, the coupling of the book’s Batson analogues is a key plot point, producing one of the book’s major villains. Meyer’s take on the Marvel Family hangs all over Moore’s take on Billy’s sexuality in the [Twilight of the Superheroes] proposal.’

So, really, that all looks pretty damning for Alan Moore. In the second part of this three-part-story, I shall attempt to see if there might be any other interpretation for all of these accusations. And in the third and final part, I’ll look to see if maybe there might not be a little tension between Moore and Grant Morrison, which might have helped to pave the way for all of this.

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

I can attest that I saw the similarities between SUPERFOLKS and various of Moore’s works well before anything Grant might have pointed out. Including the respective closing monologues of Pxysyzygy and Mr. Mxyzptlk, which don’t seem coincidental to my eye.

It’s also worth comparing the first BOJEFFRIES SAGA two-parter to Henry Kuttner & C.L. Moore’s “Exit the Professor.”

I wouldn’t make too much of the similarities between Moore’s stories and SUPERFOLKS, because it’s so simple to write about a superhero/paranormal without doing a superhero genre story. Add details, rationalize his motivations and environment–the similarities to SUPERFOLKS disappear. WATCHMEN was a literary success in large part because of the differences from superhero genre stories, not because of the similarities.

SRS

As I was reading this article, it quickly dawned on me that I read this book at some point in my life, but have very little memory of it and would never had remembered it if not for the overview and character names. A sure sign of old age!

So he’s not as talented as we all thought he was? He’s a plot stealer? Next we’ll find out it was someone else entirely who wrote all his scripts. Fuck. Maybe it was a room full of monkey’s?

It strikes me that the obvious thing that’s missing from the discussion is that Superfolks (to go by the description given) is a Superman story – that is, based on the work of Siegel and Schuster, and all the many subsequent people who’ve written about those characters. In 70+ years, everyone who’s written about superheroes is of necessity plundering other people’s ideas. Invincible, for example, is the Superman story, tweaked a little differently.

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

Fascinating article, regardless of what side you come down on.

Yes, it’s an interesting article and I look forward to the other parts.

That said, I think every writer borrows plots from their favorite stories, usually early in their career. Name a writer, find out what stories they enjoyed, then look at their work and somewhere along the lines you’ll see some similarities. Alan Moore is only guilty of being a writer. There is obviously a line that crosses into plagiarism but I don’t think Alan crossed it.

I think the same could be said of creators in other media too (music, etc..)

I started reading Miracleman while in junior high with the Gaiman issues that were coming out and I worked hard to get all the back issues. So, Miracleman is like my first big comic story that hooked me on comics. I then searched high and low for Superfolks for years and read that. My feeling then and now is Superfolks is a terrible book that Moore lifted an idea or two from. The Kid Miracleman thing in particular came straight from Superfolks (in my opinion). But still, Superfolks is an awful book and very difficult to read. Moore’s early works are all beautiful stories that are easy to read (well, Miracleman can be a chore). There’s a skill in Moore’s work he developed on his own. I’ve never agreed with Morrison’s assertion Moore plagiarized from Superfolks and got 3 books out of it.

What many of the articles about SUPERFOLKS fail to bring up is to mention the cultural circumstances the book was written and published under, which is that of the 70s post-Vietnam, Mad magazine, satirical phase of pop culture. SUPERFOLKS is really an attempt to write a novel in the style of Kurt Vonnegut at a time when Vonnegut’s books and humour were at the peak of their popularity.

There’s also the fact that the book wasn’t very good, which is one reason it didn’t stay in print, even after its recent reissues.

Speaking as a person who is not a fan of anything I’ve read by Moore I’ve got to say the connection is nothing to get the least bit excited about.

“Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is non-existent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery – celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to.”

― Jim Jarmusch

Although there may have been an 11-year gap between Grant Morrison’s first mention of Superfolks and the next time the book’s influence on Alan Moore was mentioned in print, the subject was certainly percolating in fan circles throughout that time. I’d read the novel back when it was new, and I have to admit that it didn’t make much of an impression on me. I didn’t notice its echoes when I read Watchmen, Marvelman, or Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? Somewhere along the line, though–probably through Usenet–I’d heard enough about what Moore “borrowed” from Robert Mayer that I revisited the novel in the late 90s, a couple of years before Lance Parkin’s book.

It was an enjoyable read, and the plotting parallels with some of Moore’s work–particularly the comparisons between Pxysyzygy and Mr. Mxyzptlk–were striking. Still, I agree with the thought that even if this is where Moore originally got the ideas he used, he did more with them than Mayer did in the novel. Pádraig is promising two more parts in this series, and I’m expecting the next one to be a full-throated, substantive defense of Moore against the charges.

I read Joseph Lambert’s book on Helen Keller and immediately wished Lambert had included Mark Twain’s great quote on the subject on Helen’s supposed plagiarism.

“Oh, dear me, how unspeakably funny and owlishly idiotic and grotesque was that ‘plagiarism’ farce! As if there was much of anything in any human utterance, oral or written, except plagiarism! The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism. For substantially all ideas are second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources, and daily use by the garnerer with a pride and satisfaction born of the superstition that he originated them; whereas there is not a rag of originality about them anywhere except the little discoloration they get from his mental and moral calibre and his temperament, and which is revealed in characteristics of phrasing. When a great orator makes a great speech you are listening to ten centuries and ten thousand men — but we call it his speech, and really some exceedingly small portion of it is his. But not enough to signify. It is merely a Waterloo. It is Wellington’s battle, in some degree, and we call it his; but there are others that contributed. It takes a thousand men to invent a telegraph, or a steam engine, or a phonograph, or a telephone or any other important thing — and the last man gets the credit and we forget the others. He added his little mite — that is all he did. These object lessons should teach us that ninety-nine parts of all things that proceed from the intellect are plagiarisms, pure and simple; and the lesson ought to make us modest. But nothing can do that.”

Alan Moore not original? Good grief!

Julian, there’s a few more bits to come, so I think you can rest easy that I’ll get to mentioning Superman…

Excellent quote! Yes, this is at least in part what the thrust of the second part of this is going to be about.

Ah, but wait for the next part of the story!

‘…I’m expecting the next one to be a full-throated, substantive defense of Moore against the charges.’

Yes, something of that nature, on a few different fronts.

Looking at the listing for ‘Exit the Professor,’ as I haven’t read it, I see it’s one of the Hogben stories. As Alan had suggested there was a member of the Bojeffries family called Hog Benhenry, who never actually showed up in the story, I think it’s fair to say that Moore was tipping the hat to Henry Kuttner & C.L. Moore.

I also want to point out that I wasn’t suggesting that nobody had seen similarities between Moore’s work and SUPERFOLKS before 1990, just that Morrison’s piece about it is the first mention of it I’m aware of.

RT @Comixace: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution: by Pádraig Ó Méalóid In 1977 Dial Pr… http://t.co/3QHn9v3F

I heard West Side Story was inspired by something else, too … could it be true??

This isn’t news to Pádraig, of course, but there’s a lot of early Moore that dances on the line between “homage”, “rehash”, and “plagiarism”. Moore himself describes one of his Abelard Snazz shorts as “an unintentional plagiarism of an R. A. Lafferty story” and requested that it not be reprinted. The opening of the Demon story in Swamp Thing 26-28 is very strongly influenced by the opening of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. “D.R. and Quinch Go Straight” gets its plot and tone from Ted Mann’s “The Utterly Mind-Roasting Summer of O.C. and Stiggs” (National Lampoon, October 1982). And so forth.

The evidence is that it *is* unintentional or homage, and Moore is not embarrassed to describe his influences and sources. And he moves beyond his original inspirations–not necessarily better (much as I love Swamp Thing, the Bulgakov novel is a world treasure), but into significantly different directions. Moore’s works directly influenced by Superfolks ended up being very different works from Superfolks, and generally more coherent. Superfolks is an awkward social satire with some very good bits; Watchmen is… well, a world treasure.

(Incidentally, the first place I ever saw a discussion of “Man of Tomorrow”‘s debt to Superfolks was in a Kurt Busiek fanzine in 1986. I had known of the Meyers but knew very little about it before then. One of my friends who had read both said, in response,”Yes, there’s a debt, but there’s a big difference: Moore can actually write.”)

Count me as one who found Superfolks terribly written. Even if Moore borrowed ideas from it, he made them his own.

So isn’t Mayer a bad guy as well, having stolen from Superman and Captain Marvel stories, or is this just another trashing of Alan Moore to make us all feel better?

An interesting thought, but no, the passage of the real David Brinkley had naught to do with the publication of the About Comics edition of Superfolks.

And despite what Adi claims above, Superfolks has not fallen out of print. The St. Martins edition with the Grant Morrison intro and Mike Allred cover, which came hot on the heels of the About Comics edition, is available – http://aaugh.com/to.htm?0312339925 – and the book can also be had on Kindle, Nook, and other such devices. (And for anyone who wants to check out some of Mayer’s more recent work, head to http://www.TheOriginOfSorrow.com ; it’s quite different from this.)

I’m pretty sure that Morrison has since admitted that the article was part of his attempt to portray himself as an iconoclast. There was other stuff that he and Mark Millar did in the early 90s giving some bombastic interviews, and warping old characters for their own ends to help cast themselves as Les Enfants Terribles of the comics world.

Of course, it’s pretty funny that some people got onto this train of thought because of Morrison. Gordon Rennie posted a few times about Morrison saying that his English Literature degree helps him to see where he gets a lot of the themes from and Grant is a lot less forthcoming about that. I also remember what Michael Moorcock said about him, that he’s someone who would break into your house and steal your TV and, when you caught him, he’d complement you on your choice of TV.

Sorry, but I’m not seeing the purpose of this article. You can choose any writer at random and point to 50 other author’s works that their work is derived from.

This feels a bit like a witch hunt. How many other authors read that same book? How many of those authors wrote Watchmen?

Yeah. I’m sure Shakespeare read a few plays too.

BC, Padraig has interviewed Moore many, many times and is on pretty good terms with him. Keep in mind that this is part one of three and look at Padraig’s other replies.

Just a note, I’m THRILELD to have Pádraig contributing to The Beat. I’ve long been a huge admirer of his thoughtful, well-researched pieces. And we all need to stay on him to get parts 2 and 3 up and running!

There is an interesting discussion in the back of the King Hell edition of Rick Veitch’s THE ONE. It’s a transcript of a 1989 conversation between Steve Bissette, Neil Gaiman, and Tom Veitch about how much the superhero genre had changed during the 1980s. Gaiman brought up Superfolks as an example of the revisionist superhero being played for laughs like in Mad. He pointed out that Moore took the concept “as seriously as you can” and that is why Marvelman “differed from everything before it.” Bissette and Veitch had apparently never heard of the book.

Scans in five parts at:

http://www.rickveitch.com/tag/revisionist-superhero/

…and when Neil Gaiman dives deeply into world mythology and folklore in Sandman, how do we react?

When we view comics through a post-modernist filter, what do we find?

“Merriam-Webster: Either “of, relating to, or being an era after a modern one”, or “of, relating to, or being any of various movements in reaction to modernism that are typically characterized by a return to traditional materials and forms (as in architecture) or by ironic self-reference and absurdity (as in literature)”, or, finally “of, relating to, or being a theory that involves a radical reappraisal of modern assumptions about culture, identity, history, or language”.” (via Wikipedia)

Moore’s last Superman does that, as does Watchmen and Miracleman. “What if superheroes existed in a reality similar to our own?”

Of course, once you go that route, it’s like explaining how jokes work. You pull away the curtain, you ask the reader “Why didn’t you notice this particular absurdity?”, and you burn your bridges. That’s probably the most likely reason why Dick Giordano asked Moore to change the characters in Watchmen. Better to use analogues instead of actual characters. (This is probably also the reason why “Twilight” will never be published as an Elseworlds GN.)

The bigger problem with Superman is, what happens when a God succumbs to humanity? When a Man of Steel begins to rust, does he lose his perfection?

There’s an old quote that has been attributed to many a man over the years…..

“Talent borrows….genius steals.”

Alan Moore was brilliant enough to take one thing and actually make it better….shinier.

Reread what the writer of this article had to say about SUPERFOLKS….he says the following….

“this is part of the problem I have with Superfolks – the thing is, as far as I’m concerned, it’s really not very good.”

Then he sights Kirkus Reviews…..

“Mayer should include a laugh-track with every copy, since readers unwilling to give stock responses to TV images will find this about as funny as a plastic taco.”

What we have here is Moore taking a poorly produced version of a solid concept and turning it into a superior version of the same thing.

What shocks me is everyone else’s apparent shock that Alan Moore would do this….

Of course he does it…all creative people do.

Nothing new under the sun, ladies and gentlemen, don’t ever forget that.

Now let’s hope Alan Moore takes some of Grant Morrison’s poorly concieved pieces of shit (namely 80% of everything he’s ever done) and makes them into something more than over-celebrated garbage.

‘…or is this just another trashing of Alan Moore to make us all feel better?’

I should point out that there are two more parts of this piece to go, with the next one being called ‘The Case for the Defence.’

Yes, there certainly used to be a link on Mayer’s site to buy the ebook, from Amazon I think. It’s very annoying that he re-did his site, meaning some of the stuff I wanted to quote from it is no longer there. I’ll sneak a link in to your link for the book in the next part!

Jeff,

Padraig (sorry, I always have trouble with his name due to my American keyboard) is probably the world’s leading expert on Moore’s work. Anything he writes about Moore, or anything else for that matter, should be given full attention to. His interviews with Moore over the years have been the absolute best in comics anywhere.

Robert Mayer is a pen name. For those who say the writing in Superfolks is terrible, what can you expect from Elmer Fudd? For better writing, check out my three other novels: Moby Dick, The Great Gatsby and Anna Karenina.

What Superfolks satirizes or parodies is due more to the need to have a hero fight someone–anyone–for the sake of an issue than it is choosing to write a story in a particular fashion.

I don’t know whether you’re familiar with super-science SF, but as the term implies, super-science SF stories are very similar to superhero stories. The major differences are the rules and logic applied to the narrative, so that the story makes sense, given the capabilities of the technologies used. The reader is awed by the technologies used, rather than the powers used.

SRS

Alan Moore is the new Shakespeare?! He never wrote any of his own stuff!? Holy Shit Padraig, scoop of the century!

Yes, I’ll be coming to what Morrison has to say about his earlier iconoclasm in the last part of this three-part piece.

As you mention Moorcock and Morrison, Moore has said (in the Harvey Pekar Kickstarter interview, which I have nearly finished transcribing, for reasons that are not entirely clear to me) ‘he’s the only bone of contention between me and Michael Moorcock. Michael Moorcock is a sweet sweet man – I believe he has only ever written one letter of complain to a publisher over the appropriation of his work, that was to DC Comics over Grant Morrison, so the only bone of contention between me and Michael Moorcock is which of us Grant Morrison is ripping off the most. I say that it’s Michael Moorcock, he says it’s me. ‘

Yes, as Chris says, this is only the first of three parts. I’m hoping that by the time you read part two, you will see it is most definitely not a watch hunt! If nothing else, I don’t want to get myself banned from ever interviewing Alan again.

I blush! And can I say I’m absolutely thrilled to be here. The next part is well in hand, and really only needs the disparate bits to be shuffled into place, and it’ll be done. I promise it will *not* take the nine months or so it took between offering you this and completing it.

Thanks, I’ve not got that downloaded and printed off to read in bed this evening. Unfortunately, my copy of The One is a later printing, which doesn’t have this in it.

Arse! Where it says ‘I’ve *not* got that downloaded…’ read ‘I’ve *now* got that downloaded…’

Thomas Wayne-

Your defense wouldn’t stand up in a court of children. Your attack on the brilliant Mr. Morrison is pathetic. Write something that people want to pay to read then get back to me, clown.

Methinks Pádraig wants us to post our thoughts and then wish we hadn’t when we read the next part. You’re a wily devil mate.

And congrats to Heidi for not only getting Pádraig here but John Shableski as well.

“Now with 100% more meat.”

Even if Moore does borrow heavily from SuperFolks, Watchmen is a monumental piece of work. I get the links but really so what? It’s interesting but it’s not like Moore existed in a vaccum before he wrote anything. Morrison kind of sounds like a whiny bitch, I guess until he writes something that even comes close to Watchmen he will keep trying to take Moore down.

I loved Morrison’s JLA, but the guy is an egomaniac. His work sucks, and he keeps acting like anybody cares about the $#!* he constantly talks about decnt, but still fallible Alan Moore. Wish he’d just go away.

EXACTLY.

scott

http://www.reconditepictures.com

While the question of whether Moore borrowed from Superfolks and, if so, with what degree of appropriateness is one that understandable curiosity, it really is a secondary one. The real question is whether Superfolks deserves more attention as a significant work that presaged and influenced what came later… and given the various testimonials from some of the top writing names in the field, the answer to that seems clear.

Actually, looking at you Superfolks page, I see now who Adi might have thought the book was out of print, as it does say, ‘Note: the About Comics edition of Superfolks is now out of print.’

I think Superfolks had the potential to be a better book than it is, if it had been rigorously edited. But as it stands, I’m afraid, it has less and less relevance, except as a historical curiosity piece. Certainly there are people who have good things to say about it, but it seems the majority of the commenters above share my own opinion, for better or worse.

It seems the majority of those commenting don’t state an opinion about the book, actually, and that some seem to be responding to your description and choice of citations (such as citing the earlier Kirkus review of the book than the more recent one (“sharp, funny, and ultimately moving, with a plot that could be the R-rated version of the current hit movie The Incredibles”). And some of those commenting don’t directly state an opinion but through past statements (such as Kurt) or actions (me, for example, or Mayer himself) support the book. Do some people like it and others don’t? Sure. Does that make it irrelevant? Judging by this same set of comments, there are some people who quite dislike the work of Grant Morrison; is he therefor irrelevant?

I’m sorry, I should have been more precise. What I meant to say was that, ‘of the people who expressed an opinion, the majority of the commenters above share my own opinion, for better or worse.’ It’s not exactly a scientific precise sampling method, but it’s the nearest thing to hand, right now. I’m not trying to say that everyone has to agree with me, or anything like that, just that a number of people expressed an opinion, and of those that did, the majority said they didn’t like the book.

My comment was toward the negative posts about Alan Moore, definitely not about the article. Sorry about that.

Just for the record, the author of Superfolks — that’s me — never has accused Alan Moore of anything (although a tiny slice of his royalties certainly would be accepted.) Also for the record, the comprehensive article above omitted one relevant comment about Superfolks, as follows: “You’ll never look at superheroes the same way again!” — Stan Lee.

A couple of further thoughts about those few correspondents above who did not like the book. Fair enough. Tipping the scale on the other side are the following facts: When I sent my agent sample pages back in 1976, the first editor he took it to, at Dial Press, made a purchase offer within 24 hours. Dial did a first printing of 50,000 copies, astonishing for a comic novel back then. They kicked it off with a full page ad in the New York Times Book Review. It has gone through three different editions, and has been optioned by Hollywood five times (though never made into a film, if you don’t count the rip-off “The Incredibles.”) Here is a small sample of the print reviews:

“A very funny book.”–Liz Smith, NY Daily News.

“It is gorgeous. It is splendid. It is funny as hell. He writes like an angel.” — Newsday

“A funny, cynical. mocking blend of Brautigan, Vonnegut and Woody Allen.” –Berkeley Barb.

“Infectiously funny.” — Los Angeles Magazine.

“An exuberant romp with some splendid, outrageously scaffolded jokes.” — The Spectator, London

“There are more good jokes than you have a right to expect.” — The Scotsman

It also has been published in Japanese and Italian. The point being, SOMEBODY out there liked it. And it is still available, in paper and e-book form, at Amazon, etc.

I think it’s terrific. Used to buy every used copy I saw, so I’d be able to give them to people who hadn’t read it.

And that’s aside from the fact that my career (and the direction of 25 years or so of superhero comics in general) would be wildly different without it.

Robert, thanks for replying – I would have responded to your first comment here, but I wasn’t sure if it was actually you! Although, of course, your reference to Elmer Fudd should have tipped me off, as it said on the Superfolks page on your website, before you had it redone, ‘Truth is, my favourite comic book character as a kid was Elmer Fudd.

Yes, I’ve seen those endorsements for your book, as well as Stan Lee’s quote about it. I think what perhaps we can agree on is that opinions differ, and the world would be a worse place if they didn’t. I’ve read you book a few times, and feel that parts of it are good, and parts of it are not, and other parts have aged badly. I stand by my comment that – in my opinion – it could have done with an editor being strict with it, but I understand that you may not agree with me! One way or another, you have written a book that excites opinion, and the very fact that I chose to write this series of articles proves that. Surely not a bad outcome, after all these years?

And I just want to clarify this bit, as well: ‘Just for the record, the author of Superfolks — that’s me — never has accused Alan Moore of anything.

No, I wasn’t saying you accused him of anything. There was a piece on the aforementioned Superfolks page on your site that said, ‘Here’s brilliant comics writer Grant Morrison: “Robert Mayer . . . prefigured the era of the so-called ‘deconstructionist’ superhero, which in turn spawned many of the medium’s most memorable and ambitious works.” Among the spawn, many critics say, were much of Alan Moore’s work, including the ‘classic’ Watchmen. To my knowledge Mr. Moore has never publicly acknowledged a debt to Superfolks, but you can Google Superfolks and read all about it.‘

But that only a quote from someone else’s opinion, and certainly not any sort of accusation. I will be going back to the above piece from your site in the next part, so I hope you’ll bear with me for that.

No problem. I hope you enjoy the next part, which I should be finishing off, instead of reading my comments!

“Inspiration, move me brightly”

So, The Incredibles is a ripoff of Superfolks, too? So a parody about Superman and Captain Marvel stand-ins is something wholly original that everyone stole from. As if no one else ever thought to do that kind of thing on their own. I guess Mad pre-ripped off Superfolks twenty years earlier.

I remember coming across the opening lines of SUPERFOLKS in a magazine when I was seven years old, the lines about how every other superhero had died. For decades, not even knowing where they were from (including a long period of convincing myself it was a Philip Jose Farmer story I just couldn’t track down), those lines stayed in my head, popping back up at odd moments, so that reading the reissue of the novel brought on the fullest sense of deja vu I’ve ever had.

I’m not sure which magazine it was. I want to say I was sneaking a look at my dad’s copy of Esquire? Surely you’d remember, Mr. Mayer…

People shouldn’t forget the reason that a parody is legal: it’s considered commentary on the source material. The themes in superhero stories are so evident that any two deconstructions of superheroes will resemble each other in various respects, as will two genre fiction stories. For that matter, parody and deconstruction are closely related.

SRS

Yeah, they’re pretty much the opposite sides of the same coin. That was the genius of what Alan Moore did, and Kurtzman and many others did before him, but what Moore did was take the other side, take it seriously. And once you do that, you look at a Captain Marvel knock-off like Marvelman was, and there are some things almost any writer is going to come up with.

The most interesting thing about the Marvelman story to me what the origin part, where all his Golden and Silver age exploits were basically like The Matrix.

I’m not saying Moore did or didn’t lift some ideas from Superfolks, because I have no idea, but complaining that anyone invented the idea of deconstructing genre tropes is ridiculous. Writers have the same ideas completely independently of each other all the time, especially when they’re both writing similar types of characters — A Superman parody and a Captain Marvel stand-in.

Ron, I believe that parts of Superfolks were originally published in OUI magazine, if that helps.

I see that Superfolks was featured in the May 1977 issue of Oui, but if the price for that issue is any indication, people would be better off buying Superfolks as an e-book.

SRS

Yes, this was back in the time when Morrison was revelling in a particularly spiky personality that has perhaps dogged him to some extent ever since. While his dancing around the edges of accusing plagiarism are certainly not to be taken seriously, the idea of creative inventions and borrowings are of course an area that comic fans (and literature fans) are particularly interested in.

As with the majority of comic writers (and artists), I always find it best to read their words with the hidden smiles and “nudge nudge, wink wink”‘s added in!

That said, the similarities in many comics works – sometimes influenced by their predecessors, other times wholly unburdened by the past – is fascinating in itself. It reminds me somewhat of the similar but different myths and religions that crop up in different cultures, and perhaps supports the idea of the superhero as the latest folk tale incarnation.

Mr. Fudd, I am pleased to be sharing this thread with you.

Does anyone have a scan of the illustrations which accompanied the original publication in OUI? I remember them as being quite appropriate and would nicely complement the article.

Although I can see many comparisons to Marvelman, and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow, I find the derivation to Watchmen rather strained, personally.

Although the humor has dated badly, I think its influence on the genre is immense and it merits being respected for that reason. Despite the clear MAD influences, it was the first time I had ever read an essentially serious deconstruction of the superhero genre, and when I read it as a youth (not too long after its original publication), it was mind-blowing.

Yes, where GM writes at the end of that piece in Speakeasy in 1990,

…I think it’s fairly obvious that he is very heavily flagging up the fact that he’s being sarcastic in the piece. None the less, if this kind of writing has dogged GM, what he wrote has also dogged Alan Moore for a long time now.

Absolutely, and I don’t think GM would argue with that. But on the other hand, he has praised much of Moore’s work in recent years. Along with several jokes!

On the subject of dissing fellow creators, that is one of the things that I personally find hard to align with the Moore I’ve spoken to, who is of course very warm and friendly. Moore could be an extremely effective spokesperson for comics as a genre but he frequently belittles other works – sometimes prefacing that he means superheroes only, other times not. Were I a creator working in the industry, I – and again this is just me personally – would find that to be more discouraging than being singled out.

But then I am a sickeningly cheerful person ;)

I think even comparisons to Marvelman and Whatever Happened To… are strained to call swipes, since they’re basically the same characters from Superfolks. Once you deconstructionist a superhero and take it seriously, on a character that’s a ripoff of Captain Marvel, the first idea half the writers I know would have is, “Captain Marvel’s forgotten his magic word and grown up.” Dealing with big icons like that, many writers will have the exact same ideas, and simply being first doesn’t mean anyone who does the same thing later is ripping you off.

Ed – Without having read the novel, I agree with you overall, but I think that the “mischievous imp who decides to be totally evil for a while” is… I don’t want to say a “swipe”, but it’s a pretty specific idea that I think was probably derived from ‘Superfolks’.

I think it’s worth pointing out that Superfolks itself stole from Superman. Obviously, since it’s a parody. So if Alan Moore writes a Superman story, there’s going to be a lot in common with other Superman stories and stories based on Superman stories. The idea of Mr Msdfeok turning evil isn’t earth-shattering. The idea of Superman losing his powers is pretty obvious for the “final” Superman story!

And the wierdo-corporation conspiracy isn’t really what makes Watchmen great. The chapter with Osterman on Mars is mindblowing! Little elements reflected at different scales, all through the plot, and the mental sickness of Rorschach being a much more likely reason to go out and beat up criminals, than some cliched tragedy.

And the implication that the whole “Masked Hero” fad only started because Hooded Justice was turned on sexually by beating the crap out of breathless young thugs! Sexual fetishist dresses up in perv gear to go kick the hell out of boys! If they’d only known about all the wanking HJ did afterwards, the Age of Self-Made Heroes in Watchmen would never have happened!

And haven’t even mentioned Driberg’s sexual dysfunction! He was a deep one! How much of ANY of this was ripped off from “Superfolks”?

These are just some of the many many things that made Watchmen awesome. The book’s only great because of Alan Moore’s writing and imagination. Could anyone else have produced such a work from deciding to rip off an obscure, and apparently not very good, comedy comic from years ago?

BTW some of Grant’s early “Gideon Stargrave” stuff is available to download. It’s not just terrible, it doesn’t even make much sense. The plot jumps around randomly from frame to frame, and I had no idea what anyone was supposed to be doing, most of the time. It makes disposable references to things Morrison must’ve thought were cool at the time.

Grant Morrison is self-admittedly a pretensious faker. Moore’s a down-to-Earth genius who may well be the next Buddha. I’ve enjoyed some of Morrison’s stuff, Zenith and The Filth are good. The Invisibles was all style, no substance, and no bleedin’ ending!

It’s also worth mentioning that the telephone, light bulb, and television were invented multiple times almost simultaneously by people who’d never met each other. Ideas float around like that. The existing ideas of a time, the zeitgeist, can often suggest new ones with just a short leap. Several people may make that leap independently.

Nobody lives in a vacuum, and I’d hope most comic writers are also comic readers.

Comments are closed.