So, just to recap where we left off last time: it looks like Alan Moore has based all the big hits of his career on ideas he stole from Robert Mayer’s 1977 novel Superfolks. Various people, including Grant Morrison, Kurt Busiek, Lance Parkin, Joseph Gualtieri, and even Robert Mayer himself, have claimed at one point or another that Moore based a lot of his superhero work on various aspects of the book, specifically Marvelman, Watchmen, Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, and his proposal to DC Comics for the unpublished cross-company ‘event,’ Twilight of the Superheroes. But is any of this true, or might there be another explanation? To answer that, I’m going to go through the individual allegations or suggestions, and deal them one by one, to see how they hold up.

Did Alan Moore read Superfolks?

Firstly, there’s the question of whether Moore ever actually admitted reading Superfolks. Was Robert Mayer factually correct when he said that ‘Mr. Moore has never publicly acknowledged a debt to Superfolks.’? Actually, no, he wasn’t. In Lance Parkin’s The Pocket Essential Alan Moore from 2001, mentioned previously, there’s this quote from Moore:

By the time I did the last Superman stories I’d forgotten the Mayer book, although I may have had it subconsciously in my mind, but it was certainly influential on Marvelman and the idea of placing superheroes in hard times and in a browbeaten real world.

I asked Parkin where the quote from Moore came from, and he told me that,

Moore read a draft of the manuscript and added that line himself. From memory, it’s a handwritten annotation to the proof, one of only about three comments he had.

However, it did seem as if though nobody had ever actually asked him about this. One blogger, in this post, says,

I’d love it if some ambitious journalist removed his mouth from Alan Moore’s penis and asked him about this influence.

…which is a fair point, if somewhat colourfully presented. Has anyone ever asked Moore about this? has anyone, as the writer put it, removed his mouth from Alan Moore’s penis and asked him about this influence? Yes. I have. I’ve interviewed Moore a number of times, at this stage, and always try, amongst the questions on his current work, to ask him something about his older work, or to nail down some of the stories that have built up around him. So, in an interview published on 3AM Magazine on the 17th of March, 2011, there’s this exchange:

PÓM: Right, the first thing I wanted to ask you, actually, before I get into your own work is, I wanted to ask you about Superfolks. […] Grant Morrison was at one stage intimating that you’d read Superfolks and based your entire output on it.

AM: Well, I have read Superfolks. […] But it was by no means the only influence, or even a major influence upon me output. […]

PÓM: […] I mean, when you read Superfolks, what sort of influence would it have had on you?

AM: I can’t even remember when I read it. It would probably have been before I wrote Marvelman, and it would have had the same kind of influence upon me as the much earlier – probably a bit early for Grant Morrison to have spotted it – Brian Patten’s poem, ‘Where Are You Now, Batman?’, […] and that, which had an elegiac tone to it, which was talking about these former heroes in straitened circumstances, looking back to better days in the past, that had an influence. […] I do remember Superfolks and finding some bits of it in that same sort of vein. […] Like I say, it probably was one of a number of influences that may have had some influence upon the elegiac quality of Marvelman.

An obvious question to ask here would be why, in the ten years between 2001 and 2011, did Moore go from saying Superfolks was ‘certainly influential on Marvelman and the idea of placing superheroes in hard times and in a browbeaten real world’ to saying it was ‘by no means the only influence, or even a major influence upon me output’? Perhaps it is that in his initial list of things that had been influential on Marvelman he hadn’t mentioned Superfolks, and wanted to correct this omission in Lance Parkin’s book, but found that, in the interim, the number of claims that he was somehow a giant fraud, whose entire output was stolen wholesale from this one book, had made him more cautious, and you can hardly blame him for that.

That initial list of influences mentioned above is from a very early interview by Eddie Stachelski in issue #5 of Lew Stringer’s fanzine Fantasy Express in 1983, where Moore said,

When I researched Marvelman, I tried to get right back to the roots of the superhuman and sort out exactly what made the idea tick. I read obvious things like the Greek and Norse legends again, I read a lot of science fiction stories that touched upon the superhero theme… things like [Olaf] Stapleton’s Odd John and Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. I even read a few comics.

The thing is this: Alan Moore has always been a cultural magpie, Hoovering up everything he could find, and using them in his work – the first two volumes of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen reference over eighty different works of fiction, along with work from other media, for instance. He’s hardly alone in this, but he has always been frank about what those influences are. This has already been alluded to above, and is going to be an even more prominent theme through the rest of this piece. I might as well warn you now that I am probably going to find some older – in some cases much older – examples for nearly all of the things Moore is said to have plucked from Superfolks, with only one real exception. But you’re going to have to keep reading to find out what that is. So…

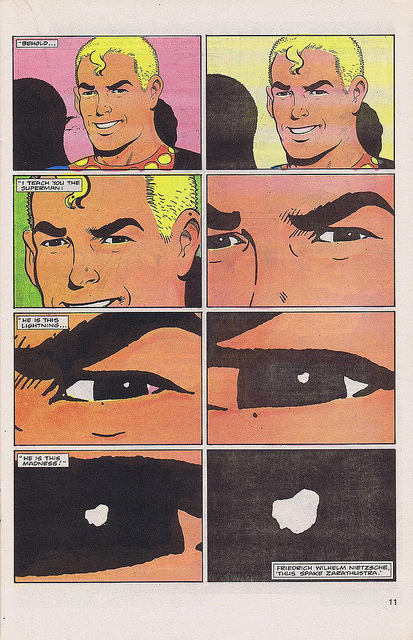

Behold, I teach you the Superman…

The next allegation I want to address is the regularly repeated one that Moore’s Marvelman story and Superfolks both started off with the same quote. Grant Morrison alluded to this in 1990, as did Kurt Busiek in 2003, as mentioned previously. The thing is, this is both true and untrue, but mostly untrue. Superfolks has as an epigraph this quote:

Behold, I teach you the Superman:

he is this lightning, he is this madness!Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Thus Spake Zarathustra

The first issue of Miracleman, as published by Eclipse Comics in August 1985, begins with a ten-page story called Miracleman Family and the Invaders from the Future, which has originally published in L Miller & Son’s Marvelman Family #1 in October 1956. This is followed by a page of eight panels, consecutively tighter close-ups on the head of Marvelman from the last page of the Invaders from the Future story, finally ending up with a completely black frame. This is accompanied by this text, broken up over the eight panels:

Behold…

I teach you the Superman:

he is this lightning…

he is this madness!

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche,

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Grant Morrison, Kurt Busiek, and Lance Parkin all point to similarities between Watchmen and aspects of Superfolks. Morrison alludes to ‘a weird conspiracy involving various oddly-named corporate subsidies,’ Busiek mentions ‘Ozymandias’s pervasive and complex commercial empire,’ which is effectively the same thing, and Parkin says that ‘The police going on strike because the superheroes are stealing their jobs is a key plot point in Watchmen,’ likening it to a similar situation in Superfolks. So, taking these one at a time…

In Watchmen Adrian Veidt, aka Ozymandias, has a business empire that includes a large number of companies that feature in the story’s central conspiracy. In Superfolks Powell Pugh, aka Pxyzsyzygy, has a business empire that includes a large number of companies that feature in the story’s central conspiracy. Certainly, there would seem to be a similarity there. However, there are earlier instances of essentially the same thing – books with characters who own a large number of companies that feature in the story’s central conspiracy – which there is a very good chance that both Moore and Mayer would have read. Pierce Inverarity in Thomas Pynchon’s 1966 novel The Crying of Lot 49 fits the description perfectly, as does Malachi Constant in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan. Moore regularly cites Pynchon as one of his favourite writers, there are references to the work of Vonnegut in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, and I would be very surprised if Mayer had not also read one or both of these books, as well. So, on this at least, it is possible that both authors were, consciously or unconsciously, influenced by earlier works, rather than Moore having only seen the idea in Mayer’s work.

Lance Parkin’s statement that ‘The police going on strike because the superheroes are stealing their jobs is a key plot point in Watchmen’ is similar to a situation in Superfolks needs a bit more examination. Yes, the police in Watchmen do go on strike – there is a general police strike across the USA in 1977 because they are afraid that their jobs are threatened by the costumed adventurers. However, there is very little similarity between this and Superfolks, where New York’s police force resign en masse after working unpaid for seven weeks, brought about by the bankruptcy of New York City, something that very nearly happened for real in the 1970s. So, on one hand we have a nationwide strike, on the other we have a city-specific mass resignation, and both are for very different reasons. Except for the fact that in both cases we have streets unprotected by the police, there’s no other similarity between them. So, again, I’m going to dismiss all the accusations about Watchmen borrowing from Superfolks as being unsafe, at the very least.

Marvelman, Miracleman, Mackerelman, etc…

Grant Morrison makes various allegations, or suggestions of allegations, about the influence of Superfolks on Marvelman. In 1990 he said:

It’s all about this middle-aged man who used to be a superhero like Superman. […] There’s another middle-aged character in a rest home, who’s vowed never again to say the magic word that transforms him into Captain Mantra. There’s a corrupted and demonic Captain Mantra Junior and loads of other stuff about what it would be like if superheroes were actually real.

…and in 2005 he said:

In his bittersweet portrayal of the middle-aged Captain Mantra, with that half-remembered magic word always hovering somewhere on the tip of his tongue, I could see that Robert Mayer had prefigured the era of so-called ‘deconstructionist’ superheroes…

Yes, both works feature middle-aged superhero characters, except that in Superfolks David Brinkley has chosen to retire, whereas in Marvelman Mike Moran has been suffering from amnesia, so there’s a difference there, straight away. Brinkley’s decision to come out of retirement is really a variation on the ‘putting the band back together’ trope, the earliest example of which is probably to be found in the novel Twenty Years After by Alexandre Dumas, originally published in serial form in 1845, where d’Artagnan tries to get the Three Musketeers back together, as you might guess, twenty years after the events of The Three Musketeers. Marvelman, on the other hand, is an ‘amnesiac hero’ story, which dates back at least as far as Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White, published from 1859, again in serial form, or to the 1918 novel The Return of the Soldier by Rebecca West, which is probably the first time that a hero in a book suffered from traumatic amnesia, which is specifically what Mike Moran has. And I should also point out that, whilst Mike Moran was middle-aged, Marvelman was not, as they are actually two different entities, unlike David Brinkley and his superhero alter-ego.

Another thing that is evident is that Morrison really wants to say that the Captain Marvel analog, Captain Mantra, had, like Mike Moran, forgotten his magic word, so that he can accuse Moore of appropriating this as well, but stops just short, presumably because he knows it’s just not true, and that there really is no correlation between the two things. Actually, Morrison really is obsessed by Captain Mantra, considering for how brief a time he actually appears in the book, as he mentions him both times he writes about the book.

Morison also mentions a corrupted and demonic Captain Mantra Junior, meaning the character Demoniac, which Kurt Busiek also refers to briefly. So, is Kid Marvelman a direct take from Superfolks’s Demoniac? Unsurprisingly, I’m going to say no. Demoniac, the Captain Mantra Junior character, is the result of an incestuous coupling between Captain Mantra and Mary Mantra’s mortal counterparts, Billy and Mary Button. As such, he’s a classic example of a type that can be traced back to Mordred in the Arthurian legends, who is Arthur’s son by one of his half-sisters, Morgan le Fay, and who goes on to fight Arthur in his last battle, and dies at his father’s hand. Kid Marvelman, on the other hand, is a classic example of the idea that power corrupts, and a direct-line descendant of Captain Marvel’s enemy Black Adam, who preceded Captain Marvel as a recipient of the powers of the wizard Shazam, but became evil over time, which is more or less exactly what Johnny Bates, aka Kid Marvelman, did. Certainly there are superficial similarities between Demoniac and Kid Marvelman, but these similarities are not unique to these two characters, and plenty of other examples of incestuous sons turning on their fathers, or sidekicks turning evil, or power corrupting are to be found in comics, in literature, and in myth and legend. And, as well as all that, Demoniac has a very brief minor appearance in Superfolks, lasting no more than a handful of pages, as compared to the major role that Kid Marvelman has throughout Moore’s run on Marvelman.

I picked up one of the Ballantine reprints of Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad which has actually got the Superduperman story in it, and I remember being so knocked out by the Superduperman story that I immediately began thinking – I was 11, remember, so this would have been purely a comic strip for my own fun – but I thought I could do a parody story about Marvelman. This thing is fair game to my 11-year-old mind. I wanted to do a superhero parody story that was as funny as Superduperman but I thought it would be better if I did it about an English superhero. So I had this idea that it would be funny if Marvelman had forgotten his magic word. I think I might have even [done] a couple of drawings or Wally Wood-type parodies of Marvelman. And then I just completely forgot about the project.

There are various other tellings of this story, from both before and after this version in Kimota!, but the basic story is always the same, and perhaps the most recent version is in this interview with Kurt Amacker on Mania.com.

As well as Superduperman, Moore also mentioned Liverpool poet Brian Patten’s poem Where Are You Now, Batman?, which he said was influential on the elegiac feel of Marvelman. When I went to look for a copy of this, I found that, much like Batman himself, it has actually been revised numerous times. This is, as far as I know, the original version, as it appeared in The Mersey Sound in 1967, before any of the revisions:

Where are you now, Batman? Now that Aunt Heriot has reported Robin missing

And Superman’s fallen asleep in the sixpenny childhood seats?

Where are you now that Captain Marvel’s SHAZAM! echoes round the auditorium,

The magicians don’t hear it,

Must all be deaf … or dead…

The Purple Monster who came down from the Purple Planet disguised as a man

Is wandering aimlessly about the streets

With no way of getting back.

Sir Galahad’s been strangled by the Incredible Living Trees,

Zorro killed by his own sword.

Blackhawk has buried the last of his companions

And has gone off to commit suicide in the disused Hangars of Innocence.

The Monster and the Ape still fight it out in a room

Where the walls are continually closing in;

Rocketman’s fuel tanks gave out over London.

Even Flash Gordon’s lost, he wanders among the stars

Weeping over the woman he loved

7 Universes ago.

My celluloid companions, it’s only a few years

Since I knew you. Something in us has faded.

Has the Terrible Fiend, That Ghastly Adversary,

Mr Old Age, Caught you in his deadly trap,

And come finally to polish you off,

His machinegun dripping with years…

You can find a slightly different version of this here; a spoken-word version by the author, again different, here; and there is also a substantially different version called Where Are You Now, Superman? here, where it is accompanied by two other poems, Adrian Henri’s Batpoem, and Roger McGough’s Goodbat Nightman, both from the same book.

Moore also mentions this poem and its effect on his work in a much earlier interview in Comics Interview #12 in 1984, where he says,

When I was about 16 or 17 I got involved with Northampton Arts Lab, where you’d get together with some people, hire a room, put out a magazine, do performances. I learned a lot about timing in comics from acting, and I learned how to use words really effectively from poetry. There’s a poem by Brian Patten called ‘Where Are You Now, Batman?’ It has a haunting line about ‘Blackhawk has gone off to commit suicide in the Hangars of Innocence.’ It made you think, ‘Ah! If only they’d look at those characters with a bit of poetry in the comics themselves!’ I think that’s where my attitude came from.

Twilight of the Superheroes

[Moore] clearly internalized Superfolks to such a degree that he never, ever makes note of the fact that Mary and Billy Batson’s relationship is an incestuous one. For those unfamiliar with Superfolks, the coupling of the book’s Batson analogues is a key plot point, producing one of the book’s major villains. Meyer’s take on the Marvel Family hangs all over Moore’s take on Billy’s sexuality in the [Twilight of the Superheroes] proposal.

The thing is this: DC’s Silver Age started in October 1956, Marvel Age in November 1961. By 1977, these were 21 and 16 years in the past, respectively. And in 1977, Alan Moore was 24 years old, and had been reading comics all his life. But he’d also been reading lots of other things in that time, as well. Certainly any adolescent comics reader would be likely to have speculated on what might actually happen if Clark Kent and Lois Lane ever finally did go to bed together, and even to have considered that perhaps Superman and Wonder Woman would have made a good match, as Moore suggested in Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? And Moore was obviously aware of things like Tijuana Bibles, as they feature in both Watchmen and League: Black Dossier, where he even creates his own. But what about the sexuality of the Marvels in his Twilight of the Superheroes proposal? Here’s the relevant piece:

House of Thunder

The House of Thunder is composed of the Marvel family, plus additions. Captain Marvel himself is the patriarch, and is if possible even more estranged and troubled by the state of the world than Superman is, perhaps because the Marvel family are having to come to terms with the difficulties of having human alter egos along with everything else, a point I’ll return to when I outline the plot. Alongside Captain Marvel, there is Mary Marvel, who the Captain has married more to form a bona fide clan in opposition to that of Superman than for any other reason. There is also Captain Marvel Jr., now an adult superhero every bit as powerful and imposing as Captain Marvel in his prime, but forced to labor under the eternal shadow of a senior protégé. To complicate things, Captain Marvel Jr. and Mary Marvel are having an affair behind the Captain’s back, Guinevere and Lancelot style, which has every bit as dire consequences as in the Arthurian legends. The other member of the Marvel clan is Mary Marvel Jr., the daughter of Captain and Mary Marvel Sr. Mary Jr. is fated to be part of a planned arranged marriage to the nasty delinquent Superboy during the course of our story, in order to form a powerful union between the two Houses.

Surely it’s not hard to see that the kind of dynastic intermarrying that is going on here is much more likely to be influenced by things like the ancient Egyptians, where sibling marriages were commonplace amongst the Pharaohs? And Moore himself references the Arthurian elements in this. Again, I think his influences are far more likely to be from other sources, and from his wider reading, than they are from the sole influence of Superfolks. Certainly the idea of there being a dynastic structure to the different groups, and that they would marry off their offspring for political purposes is his own, but straight out of European history, right up to the present times, nearly.

Whatever Did Happen to the Man of Tomorrow?

There is one final allegation of the influence of Superfolks on the works of Alan Moore, and it is perhaps the most troubling, at least to me. In September 1986 DC published the two parts of Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, beginning in Superman #423 and ending in Action Comics #583, a story which was meant to be the last Superman story of the Silver Age, ahead of a reboot of the character by John Byrne in the wake of Crisis on Infinite Earths. In his introduction to the collected edition of the stories in 1997 Paul Kupperberg quoted DC editor Julius Schwartz on the difficulty he was having deciding who he should get to write that ‘last’ Superman story:

The next morning, still wondering what to do about it, I happened to be having breakfast with Alan Moore. So I told him about my difficulties. At that point, he literally rose out of his chair, put his hands around my neck, and said, ‘if you let anybody but me write that story, I’ll kill you.’ Since I didn’t want to be an accessory to my own murder, I agreed.

It’s this story that has perhaps the most pointed comments about its being influenced by Superfolks. In 1990 Grant Morrison alluded to ‘a simmering plot to murder the Superman guy and unleash unknown horrors on the world, […] In the end, the villain turns out to be a fifth-dimensional imp called Pxyzsyzgy, who has decided to be totally evil instead of mischievous,’ and in 2005 he said that ‘In the conspiracy themes, […] [and] fifth-dimensional science […] of Superfolks, we can almost sniff the soil that grew so many of our favourite comics in the ’80s, ’90s, and beyond.’ In 2001 Lance Parkin said that ‘Superfolks and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? have the same ending – a formerly mischievous but now truly evil pixie character is behind the events of both.’ And in 2003 Kurt Busiek says ‘Look at the work of Alan Moore, possibly the most significant creator the field currently has of superhero stories that break with formula and expectation and inspire others to do the same and you’ll see this book’s influence throughout […] Mr. Mxyzptlk’s motivations and revelations in the finale of The Last Superman Story, and more.’

And they’re right. The ending of Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? is very similar to a scene in ‘Superfolks. In Mayer’s book, Brinkley asks Pxyzsyzgy,

Why, Pxyzsyzgy? You used to happy with pranks, with mischief. The Cosmic Trickster, that’s your role. Why all this? Murder, intrigue…?

And Pxyzsyzgy replies,

Cosmic Trickster, shit. I’m tired of playing the clown. Call it Fool’s Lib. From now on there will be death, destruction, disease.

Although I should point out that he’s saying this as he’s being banished back to the fifth dimension…

Meanwhile, in Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, Mr Mxyzptlk says,

The big problem with being immortal is filling in your time. For example, I spent the first two thousand years of my existence doing absolutely nothing. I didn’t move… I didn’t even breathe. Eventually, simple inertia became tiresome, so I spent the next two thousand years being saintly and benign, doing only good deeds. When that novelty wore off, I decided to try being mischievous. Now, two thousand years later, I’m bored again. I need a change. Starting with your death, I shall spend the next two thousand years being evil!

So, yes, there is a great similarity between Pxyzsyzgy and Mr Mxyzptlk. There is another similarity between the two of them, though: in both cases they are no more than plot device, someone there to represent an ultimate evil that has been behind the scenes all along. And in both cases they appear for exactly three pages before being dealt with and defeated by the stories’ protagonists. Certainly, in Superfolks, we are shown Powell Pugh, Pxyzsyzgy other identity, being involved from the start of the book. However, in Man of Tomorrow, until Mr Mxyzptlk turns up, Moore could have chosen anyone as the Man Behind the Curtain.

It is possible that there might be more of a reason than a conscious or unconscious memory of ‘Superfolks in the choice of Mr Mxyzptlk as the bad guy. In that same introduction to the collected Man of Tomorrow, Kupperberg goes on to say,

So, in a letter to Moore dated September 19, 1985, Julie [Schwartz] proclaimed, ‘The time has come! Meaning: that I’ve just been informed that the September cover-dated issues of SUPERMAN and ACTION will be my last before John Byrne and Co. take over. What I’m getting at is: the time has come for you to type up the story your ‘mouth’ agreed to do – that is, an ‘imaginary’ Superman that would serve as the ‘Last’ Superman story if the magazines were discontinued – what would happen to Superman, Clark Kent, Lois Lane, Lana Lang, Jimmy Olsen, Perry White, Luthor, Brainiac, Mr. Mxyzptlk, and all the et cetera you can deal with.’

If this is the actual content of the letter, and not a post-factum version of it that handily matches the content of Moore’s story, then it does seem that Julius Schwartz has given Moore a very exact menu if who he wants in the story, specifically including Mr. Mxyzptlk. And there is another possible reason why Moore chose to use Mr. Mxyzptlk: In Superfolks Pxyzsyzgy is only banished back to his fifth dimension home, and can return to Earth in four years, by which time Brinkley will be completely powerless. Perhaps Moore couldn’t help wanting to find a better and more permanent solution to the problem, and having found it, really wanted to use it. Certainly, for my money, that scene when Mr. Mxyzptlk is finally dispatched is one of the scariest in comics, and a much better way of dealing with the bad guy.

So, this, and only this, is where I think Moore borrowed from Superfolks, whether consciously or unconsciously. That’s not to say he might not otherwise have been influenced by it, of course, or that the book does not have an interesting and possibly even important place in the development of how comics were brought to a more realistic and sophisticated place than they were before it was written.

There is no doubt that, at its heart, Superfolks is a parody of Superhero comics, and of Superman in particular. Indeed, it’s so close to DC’s Superman that it’s a wonder that DC didn’t actually take action, as this is something they’ve often done in the past. None the less, for a writer who claims that he gave up reading comics at the age of 12, and that his favourite comics character is Elmer Fudd, there is much of worth in Superfolks, if you strip away some of the silliness it contains perhaps a little too much of. And, while it probably owes at least some of its own roots to things like Marvel’s Not Brand Echh, and to Mayer’s own background as a journalist, equally we can see its influence in many modern comics, and even in things like the TV show The Greatest American Hero where, in imitation of David and Pamela Brinkley, we find Ralph Hinkley and Pam Davidson.

Obviously, in all of this, I’m very much taking Alan Moore’s side, but even so, I do honestly believe that many of the claims made about his appropriating ideas from Superfolks are either mistaken, exaggerated, or just downright wrong. I had hoped to say something about the vast array of influences that can be seen in Moore’s work, from the influence of Monty Python’s Bicycle Repair Man on his work in general, to the much more specific influence of the opening of Philip José Farmer’s To You Scattered Bodies Go on the idea of where the spare bodies are kept in Marvelman. But I really think I’ve gone on about this long enough.

There is one final part of this examination of Alan Moore’s relationship with Superfolks to come, however, called The Strange Case of Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, which will appear here soon.

Gosh! I didn’t know this had gone live. Fantastic!

This is a very interesting examination of one author using his influences to create other works. Bear in mind that books like Superfolks has been around for a long time. It’s not as if it was only Alan Moore who had access to it. Plenty of other writers have seen and read it. And yet it is only Alan Moore who was able to use that influence and create works of lasting impact and enduring quality as Marvelman and Watchmen.

I’m surprised that such a big issue is being made from an artist using influences to create their own works. Hasn’t this how most artists have always created? That Alan Moore got more acclaim out of doing it is perhaps the very root of all this attention and scrutiny.

You fail basic High School debate, with the conclusion that maybe he didn’t JUST rob Superfolks, he probably robbed from multiple sources. But your premise as per the title is whether he stole from Superfolks. This is incontrovertible and no amount of verbal gymnastics will change that.

Ideas cannot be protected though and had you argued that Moore stole a lot of Mayer’s ideas and did then between 50 and 100 times better you would be correct. As it is you are not.

Alan Moore gets this type of scrutiny because he’s considered one of the best comic book writers out there and people want to knock him down a peg for various reasons.

Yes, that’s very much one of the reasons I wanted to write this. It was the very fact that people said it so often that made me curious about it. Obviously all creators of all kinds borrow, steal, are influenced by, adapt, and in all sorts of other ways interact with works that have gone before them, and we are all, for better or ill, the product of all the things we have experienced and been influenced by, whether we know it or not. I could write a very long piece indeed trying to track down all the influences on Alan Moore, but it’s really only this book that gets used to berate him with, so I wanted to address it particularly.

Well that and you want to slag off Grant Morrison while keeping your mouth on Alan’s penis, or even worse, retaining the CHANCE that you might get to taste it again.

Every great story teller strip mines the previous works that enflunces them….in the end its all about who tells the better story. Who cares if Alan Moore took the same basic concept of SUPERFOLKS and produced other work with it…the key is Alan Moore did it better.

We wouldn’t even be discussing SUPERFOLKS if it wasn’t for Alan Moore.

Any Tarantino fans out there? He steals from EVERYONE AND EVERYTHING and is praised as a cinematic god for doing it. Just ask Ringo Lam about CITY ON FIRE….err….that is….RESERVOIR DOGS. They are the same basic film….Tarantino just made it better. This is what Moore did, he took a concept and made it better. It happens all the time, in all forms of creative enterprise. Ever watch an episode of CSI and think, hmmmm…thats kind of like an episode of CRIMINAL MINDS. I’ve seen episodes of both POWERPUFF GIRLS and MY LITTLE PONY that riff on parts of THE BIG LEBOWSKI. Could a movie like CHRONICLE even exsist if it wasn’t for SUPERMAN, XMEN and any number of other comic inspirations?

Alan Moore did nothing more than take a weakly produced story and turned it into a critical legend.

On a secondary note…anyone here remember SWAMP THING? V FOR VENDETTA? THE KILLING JOKE? FROM HELL? A SMALL KILLING? All the ABC comics like PROMETHA and TOM STRONG? LEAGUE OF EXTROIRDINARY GENTS? If Alan Moore is such a hack that he has to steal from a little known book to build his legacy, whats his excuse for these other great works? Who did he blatantly steal from to write THE ANATOMY LESSON in SWAMP THING? Where did he come up with the KILLING JOKE?

Its ridiculous to think that somehow Alan Moore is less of a writer because he might have taken a concept from another writer. IT HAPPENS ALL THE TIME…IN EVERY FORM OF ART. George Lucas stole blatantly from the Wizard of Oz for his characters. The Punisher is essentially a super hero version of Dirty Harry.

I say get off Alan Moore’s back. He’s a great writer who appears to be getting attacked for the sake of Grant Morrisons childish ego.

I wouldn’t say that Morrison was “obsessed” with Captain Mantra, as that’s a rather loaded term. He’s a pretty memorable character in the book when you go into it already being aware of Marvelman. Morrison has a pretty encyclopaedic knowledge of superhero history, so it stands to reason he’d mention Mantra.

I think really that a lot of the musings on what was and what was not influencing Moore can only really be answered by the man himself. The comparisons between his work and Superfolks are fascinating to see, and whether they be coincidental or not, I think it’s maybe a tad too biased to write off most of them as non-influenced.

I hold no real opinion either way mind, I just don’t think the evidence as it is supports either the case for the prosecution or the case for the defence.

And not to pick a fight(!) but I’m a little confused as to why Morrison in particular is being pointed at.

And it would help if I could post under my complete name…don’t want that Thomas Wayn guy getting all my pub….lol

People often overreact to similarities in storylines, partly because they’re used to seeing writers recycle material, and partly because the archetypal serial superhero is so simple. Consider his makeup: origin, motivation, power(s), love interest, and archenemy. The options a writer has for dealing with any element are limited, especially where the motivation is concerned. If the hero isn’t compelled to fight crime, or doesn’t treat fighting crime as his occupation, he won’t be a crimefighter. It’s not something he can do on a case-by-case basis.

There’s not really any aesthetic basis for focusing on the similarities between any of Moore’s works and others; doing so suggests the critic isn’t aware that the differences in the details of any two genre fiction stories are what matter.

SRS

Don Murphy — do you have an Alan Moore google alert set up or something?

Gary and Thomas — I think you get to the root of the matter. Moore doesn’t have just one work but an entire BODY of work spanning 30 years that contains many groundbreaking, memorable works. And who knows what his novel will be like when i finally appears. Padraig has done an admirable job of researching one aspect of Moore’s very notable career.

This article and the one before it were very interesting. I never knew that Alan Moore was a fan of Thomas Pynchon, but now that I do, it makes a lot of sense.

And Alan Moore has already released a novel. Voice of the Fire.

http://www.amazon.com/Voice-Fire-Alan-Moore/dp/1603090355/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1352692874&sr=8-1&keywords=voice+of+the+fire+alan+moore

Think these guys realize Alan Moore is another class as a writer so looking for something that may knock him down a peg or two, even if can be argued this 70’s Superfolks thing maybe got him thinking. Are they capable of making something as dense and inventive as the Watchmen or as complete a story? Not to mention the 12 other things Moore has done were syphoned as movie properties. Is anybody trying to release SuperFolks in a unscrupulous way to make big money like DC is doing to each character of Watchmen…

Moore is till doing inventive stuff as we speak, not rehashing 80’s plots about a gang of Santas with guns. Perhaps its hard to accept but that guy is the real deal.

I thought you failed HS debate when you resorted to calling opponents gay or suggesting they perform sexual acts on men.

Moore is my favorite writer of any form of story. I just kinda hate how polemically enraged the discussions about his work have become.

Padraig – You have turned in yet another awesome article. It’s so weird to see a Pynchon reference, though. The other night I had a dream where Pynchon was speaking at a class, but I couldn’t see him because there were too many people in the way. So, all weekend I’ve been reading stuff on-line about him.

Thomas – Excellent comment. I really enjoyed that one.

I’m loving these articles! Please keep them coming!

He has another one on the way called Jerusalem. It’s going to be like 1,000,000 words or something. It sounds pretty cool.

Padraig – The mention of a discussion with Byron Talbot has me wondering – did you ever publish an extensive interview with him? That would be fascinating!

You sold me – the nails are in the coffin on that one. It always seemed odd to me that Alan would be solely influenced by one novel on his superhero work, yet draw from a variety of sources for everything else he did – influences mind you, he’s work’s all uniquly him.

Interesting to see how those who have made the accusations will respond to finding out they just aren’t as well read as Alan was. It was kind to wait until after Morrison-con to run this.

Well, maybe ‘obsessed’ was a bit of an overstatement! But he certainly seemed to latch on to the character, who really isn’t in the book for very long.

The thing with the influences on AM’s work was that, while we can guess at some very easily, other are not so easy to see. I added a few at the end because they seemed likely to me, and because I want to link to Monty Python’s Bicycle Repair Man!

Was I pointing at GM overly, do you mean? I do think his part in all of this is important, but in the end I’m only using what he said himself, and I hope fairly. In the final part of this, I do attempt to divine the relationship – using the term, as Stephen Fry would say, quite wrongly – between AM and GM more fully.

I do fully put my hand up to the suggestion of bias on my part, though. I am obviously on Alan Moore’s side in this, but I hope this didn’t stop me from being as impartial as I needed to be. In the same way that you are obviously on Grant Morrison’s side – things we both knew about one another for quite some time now!

Yes, I’ve always felt that at least part of the reason for the prevalence of the idea – particularly as seen on Internet boards, posted by people who have probably never read Superfolks – is that it somehow brings him down to Earth, if you can suggest he ‘stole’ all his ideas. Obviously, as stated in the comments here and previously, it’s not the ideas you have, but what you do with them, that matters. I would point at Superfolks itself as an example of this: there are some really good ideas in there, but overall it fails as a novel. Some judicious editing, and a few re-writes, and it might have been a very different book.

Thanks, Chris. I do have a few more pieces in a similar vein I’m going to pitch to Heidi, so hopefully you’ll like them, too.

Yes, as it happens, I did a long interview with him a few years back: Part One and Part Two, from October 2009, are on the Forbidden Planet International blog – actually, all my interviews there are collected together here

I do love seeing the more obscure references, particularly as I’m one of those people who misses so many of them when reading LoEG (I blame my youth!). I think from my own view, I’d say that Moore was influenced by Superfolks, amongst all other sources, but that it doesn’t really matter – everyone is influenced by everyone, it’s what you do with it that counts. I suppose it’s more of a sticky point when it comes to Moore as he is so down on every comic written at DC after him, and his tendency to fall out with good people.

The quotes from Morrison are true enough, but only the oldest one really points to Moore in particular, rather than the broader influence of Superfolks within superhero history, and it was written a very long time ago, and in a non-serious manner. Not that that discounts it, but really, Morrison has said very little about Moore, or certainly very little that is negative, over the years. In fact, I think he’s quite deliberately stayed quiet on the subject, which is why it seems odd to focus so much on that one column from 1990.

I do fully admit to my own bias of course! But that’s partly because I think he’s a great dude, and partly because kicking him seems to be rather popular at the moment.

I hope that by the time you see the final part of this, you’ll allow that I’ve been as fair to GM as I can, in all this.

Yes, I do seem to be hearkening back to that 1990 article a lot, but I think it has echoed down the years perhaps more than he could have imagined it would, and has been used as a stick to beat Moore with quite a bit. I have no axe to grind with Morrison, and I certainly agree with you that he is has generally only ever said good thing about Moore, for quite some time now. Because my aim was to examine what had been said about Moore vis a vis Superfolks, I suppose I had to engage critically with Morrison’s piece, although I really do not believe it reflects his views now, or possibly even then. I think he’s astute enough to know that any creator has influences – certainly his own early work does, which he readily concedes.

I think any good writer – any creator of any kind, indeed – will acknowledge that they have many influences, and be very happy to talk about them. This obviously includes both Moore and Morrison.

One particularly unseemly aspect of Morrison’s review of Moore is that he is directly competing with Moore. More than most, Morrison is cut from the same cloth, walked the exact or nearly exact same path to success. The family of deconstructionist counterculture superheroes is small. How much of it is Morrison seeking to close or surpass the gap by bringing the top down rather than the bottom up?

We could look at Alan Moore as we look at Bob Dylan: a man who immerses himself in ideas, both of his own and those of others. Then scoops, borrows or amalgamates them all together, adds his own twists, and releases it as his own interpretation. For Dylan, it can be a new version of a folk song, or a thinly veiled swipe of another poet’s work, set to music. Some would just label that ‘theft’, others call it poetic license.

There you go thinking again, not your strong suit “Jesse”!

No, I read your blog regularlu, is that something you would rather people not do?

And as somebody who knows both gentlemen first hand, unlike almost all of the commenters, I find it astounding that someone with grace, honor and people skills (Grant) is being attacked by somebody whose sole significance seems to be a plethora of accent marks in his name in favor of someone who has lied, thrown friends under the bus and cares only about his own faulty reputation (Alan). But it is your blog do as you wish. As the election showed, those on the wrong side of history get left behind.

Interesting, my comment wherein I pointed out that any attack on Morrison would be met by the strictest defense possible has been deleted. So much for “Speak Your Mind.”

This one?

https://www.comicsbeat.com/alan-moore-and-superfolks-part-2-the-case-for-the-defence/#comment-221241

I haven’t deleted any of your comments THIS T IME. But no name calling! Thanks for reading.

And you fail at basic manners, sir.

Agreed, we wouldn’t want to get any of your anonymous posters butthurt by calling them names while they attack a talented comic book creator would we? Oh the HUMANITY!

Agreed. I probably should have been more polite to the guy who is needlessly trying to stir shit up about people. Winnah!

Don,

I have a theory on Grant Morrison and all of his “followers and endorsers”….its along the lines of why TWILIGHT and 50 SHADES OF GREY have reached immense popularity during the internet age.

It used to be a creator or creation took some time…at least a few years…to become a cultural phenomenon.

Look at Alan Moore as a perfect example….his rise started with Marvelman…hit new stride with Swamp Thing…and Watchmen sent him over the top into a new level of creative genius and with that a new level of popularity.

Frank Miller is another example….his Daredevil work….then onto the Dark Knight which, again, sent him even higher…then Year One..onto Sin City…and so on…his legend was built over years and various works…

Now…this happened at the beginning of 24 hour news cycles and such…but no INTERNET…so it wasn’t like we had a “like” button to click on our facebook pages to show our love and respect for Moore and MIller.

Now…in today’s culture of overt social sharing online…it has become not only a must, but the social norm to “like’ what everyone else likes.

This is at the heart of the rise of books like TWILIGHT and 50 SHADES OF GREY….a core group (in this case mostly female fans) all want to be socially active within the same group…so the popularity of stuff like TWILIGHT and SHADES is based in being part of the “group” not based in actually liking or loving the work itself. The like or love may happen after the fact…but initially its people who want to fit in…this is how critically panned crap like TWILIGHT survives and even thrives. Call it the Oprah affect….Oprah would choose a book and it would sky rocket to the top of the sales charts…didn’t matter if it was actually good…all that mattered was millions of woman wanted to be part of Oprah’s social network via this book club and there ya go…instant “liking” of a book based on being part of a group.

This brings me to Grant Morrison and his current place at the top of the comics heap….at least based in name.

When you look at Morrison’s body of work its all over the place…some of it is fairly good…I love his JLA stuff from the mid 90’s and have gone out of my way to praise it at any and all opportunities….but after that…you get a lot of stuff that’s praised because…well….he’s Grant Morrison. He is praised by everyone else, so a lot of fan boy types praise him to be part of that social group. I did a little expirement a few months back at a comic shop in Tulsa during their anniversary party…place was filled with fan boys and of course many a “comic” oriented discussion had broken out…so with me and my big mouth I asked the room….roughly 35 to 45 people…ages ranging from 15 to 55….who was the best writer in comics today…..there were a couple of Scott Snyders…..A Bendis…a handful of votes for Jason Aarron….but more than 20 people said Grant Morrison. Roughly half of everyone there. So I asked those who voted for Morrison why they voted for him and what was their favorite Morrison book of past or present. Amazingly only 3 of the 20 could give me an answer. The other 17 simply said “I don’t know”…they based their answer off what they assumed everyone else wanted to hear so they could fit in. Now, you could just chalk it up to these men not having much of an imagination and just spouted out a name…but why Morrison? Why not spout out Bendis, or Snyder or any number of writers? I believe its because they have a need to fit in…so go with Morrison. He’s popular and great…but no one seems to know why was the way I perceived it…lol.

Morrison is a solid writer….no doubt…with a solid body of work….but in the pantheon of great comics he really has more misses than hits…..on a large scale I don’t see anyone championing THE INVISIBLES as an absolute must read…maybe his ANIMAL MAN run but that to can be an acquired taste…his ALL STAR SUPERMAN is loved by many but I know quite a few folks who felt it was not nearly as great as some make it out to be. And don’t even get me started on the total ankle grab job his work on BATMAN was prior to the NEW 52. Its almost as bad as the supository of nonsense that FINAL CRISIS was.

There are numerous writers who have just as good if not incredibley better bodies of work than Morrison (Bendis, Azzarello, Garth Ennis, etc) and you never hear them get the praise that Morrison does. Why? I think its as simple as clicking the “like” button….fan boys…like most groups of people…just want to fit in…be part of the group. This is why Grant Morrison gets so much adulation and love…not based in an actually love of his work…but a need to be part of a social group.

That wouldn’t really explain why when I interview Morrison, as opposed to the various other (great) names in comics that I’ve spoken to, I get actual hate mail, with some critics going so far as to email me support that they don’t feel comfortable sharing on their own sites.

Somewhat off topic but certainly it’s not the case that it’s cool to be a Morrison fan in all cases!

I just examined my copy of Supergods, which is Grant Morrison’s autobiographical account of the “new comics”, with extensive reference to Moore and the eighties. There’s no mention of Superfolks in the index, and he manages detailed discussions of Marvelman and Watchmen without mentioning the book.

I don’t want to step on POM’s toes, but my own initial conclusion was that Morrison was teasing when he made the accusations of plagiarism, and he’s now sick of the whole business. He doesn’t really want to mend any fences with Moore, but he doesn’t want to pursue a vendetta that neither of them are interested in.

As to the ideas in Superfolks – as has been demonstrated above, most of the ideas therein are variations on things that have been in the mix for a long time. A mischievous character turns evil? That’s pretty much the SOP for Batman for years. The reclusive superhero who’s comes back? I’m reminded of The Human Torch giving a bum a blow-torch shave and revealing an amnesiac Namor. And wasn’t that shaving bit lifted whole from Desperate Dan?

Re-using old tropes in different ways is what superhero comics have been doing for half their history. Spiderman was an effort to imagine a superhero in the real world.

It’s maybe worth noting that the only example of legally proven plagiarism was when Captain Marvel was judged to be a copy of Superman. Or was he? Someone should write a book about that. Certainly the concept of a very strong man was regarded by DC as being something that they came up with.

Many of the examples are really quite trivial. A police strike? This was a very minor element in Watchmen. The incest theme? Alan Moore doesn’t need prompting to include an incest theme. He sprinkles them over his work like confetti.

I do want to say – again – that it is not my intention to do down Grant Morrison in any way. I wanted to examine what he and others had said about this, particularly because it still seems to be prevalent, all these years later. I think, much like happens with Moore, people like to belittle those in the public eye, and Morrison is no exception to this treatment. Obviously, both of them can polarise opinion – as we can clearly see here – but the only real way to get to the bottom of these things is to examine them as robustly as we can, rather than by rudeness.

I feel like these articles are fundamentally flawed in their understanding of what writing is. Alan Moore and Grant Morrison are both great writers, and both have a ton of influences, as do all writers. Tracing basic ideas back to their “originator” like this is like finding out who hit the first homerun and saying everyone since then has been copying that guy.

“I don’t want to step on POM’s toes…”

Too late! The fact that GM doesn’t mention Superfolks in Supergods was going to be one of the ‘reveals’ in the third part of this book. Thank god you didn’t look at the epigraph on Supergods…

“It’s maybe worth noting that the only example of legally proven plagiarism was when Captain Marvel was judged to be a copy of Superman. Or was he?”

Nope. The case was settled out of court, so there was never an actual proven case. Also, nope again, as there *were* other cases where DC *did* win their suits. Lots more about it here.

“Someone should write a book about that. ”

Thanks for being my straight man, Julian. Yes, once I find a publisher for Poisoned Chalice: The Extremely Long and Incredibly Complex Story of Marvelman it’ll all be revealed!

One might say that parodies and deconstructions are inherently derivative.

SRS

Precisely

Originality is a myth.

Unless the book reveals the truth (the copyright is owned by the British Government and no one else) I can”t imagine many sales.

I’d like to think that wasn’t what I was doing. Specifically, one of the things I wanted to do was to look at various allegations about Moore & Superfolks that I’d come across, and see if there was another way of looking at them. They weren’t my allegations, but just things I became curious about – and particularly because of the enormously long life these allegations have had. What I wanted to do was to see if I could find any earlier examples of what were being said to have originated in Superfolks, and to speculate if Moore might have come across them.

Explain to me why the copyright in Marvelman is owned by the British government.

The Queen took all proceeds in the initial bankruptcy.

The idea that Mick Anglo had anything to sell to Marvel is a cosmic joke.

Your premise though is bass ackwards.

OF COURSE he stole a lot of ideas from SF. And then did them better.

So what is your premise then? That he took ideas from SF? Of course he did.

Mr. Brubaker, I agree whole heartedly – I find it interesting to know an author’s influences, but just because they were influenced, doesn’t mean they stole from it, or that it’s anything more than a book they had read once that played with similar ideas.

But as is pointed out, other writers including Grant Morrison, Kurt Busiek, and the author of Superfolks, have referred to Moore being overly indebted to Superfolks. More than a “Moore was influenced by this” there’s been the hint that he may have just taken parts wholesale and used them in his work.

The accusation gets repeated by Moore’s critics on message-boards and such, and if it was just fans looking to justify buying Before Watchmen or trying to knock the guy who made fun of Blackest Night, then it would require as much in-depth journalism as those claiming Moore plagiarised with League Of Extraordinary Gentleman – anyone making the claim is clearly clueless.

But when the claim is coming from other writers about his early works? That gives it a bit more weight.

Brilliantly, it turns out Alan wasn’t just downplaying Superfolks to hope people didn’t see it had been a massive influence, it’s just he’d seen it all before when Superfolks came out, so it never made him as happy as it did Mr. Busiek, and Morrison was working backwards from Marvelman to Superfolks in his reading – yelling “aha!” as he went through – rather than reading back from Superfolks to see where it came from.

The only thing missing now is for Moore to write a history of superheroes/autobiography where he can make backhanded compliments about Morrison’s work throughout, and they’ll be even.

(Actually, Moore likes a good structure, so he’d probably come out slightly ahead).

Ask me, you write a book about superheroes growing up and you want to play ‘what would happen in the real world’ – good chance is you’re going to come into some similar ideas as other people who have done it, even if you haven’t read their work.

Awesome! I’m going to spend the next few days catching up! I wasn’t aware you had interviewed anyone other than Moore!

Thomas,

I don’t think you’re trying to be a contrarian or do anything other than offer an idea, but I don’t agree. Morrisson isn’t my favorite writer, but he is very, very good. I think his Seven Soldiers book was pretty insanely great. He kept putting idea after idea in it and made it all work as a story. Granted, he has some spectacular misses, but I think anyone who tries for greatness is going to have one or two misses.

Insult the fights’n’tights and the babymen will come for you with a thousand tiny daggers and lemon juice to pour over the cuts.

So, there should never be any articles written about what influenced an author?

And, as Ben Lipman said, there have been numerous accusations over the years Moore has stolen ideas wholesale from specific books. Isn’t it interesting to read a series of articles about how likely or unlikely that is?

@William George- I know some people will never miss an opportunity to smugly make fun of superhero fans, but this debate about whether or not Moore stole some ideas really has nothing to do with the genre involved. No one arguing either side is actually insulting or defending “fights’n’tights”.

But, hey, why let context slow down judging others over the Internets, right?

But there’s NO QUESTION that he has stolen hundreds of ideas. None of his ideas is original. What he does with them is. So what is the point?

There is no debate to be had. He applied the media he was consuming into his work. Kirby did the same thing. The difference is that Kirby didn’t tell the fights’n’tights industry/fan base to go get fucked. That’s why a lot of effort has been made to tear him down. Otherwise no one would care where he drew inspiration from and this article wouldn’t have been written. There’s your context.

And it’s always a good time for scorn. If comics culture doesn’t make you scornful, you’re not paying attention.

Yes, its clear I have never read SuperFolks but I don’t doubt you that it must have been noticed or an influence on Moore for Watchmen, your panels & quotations make clear sense of that. It looks pretty original too. Oddly enough, I think a third of my posts on this blog have been in some kind of defense of Alan Moore and I’m don’t know if I’m even one of his superfans. Just read only 2 of his books- Watchmen & Killing Joke, maybe some excerpts from others. Saw a movie or two. But pretty clear to me he’s some kind of genius who maybe borrows a little everybody does as pointed out here, but still original like Stan Lee. Another writer who Moore himself plays the skeptic role in order to cut Stan Lee down a peg or two in the name of defending artists who lack credit, but its undeserved in the same way, Stan Lee’s the real deal too. And Stan goes out of his way to give those guys credit now. That he larger than life than all the rest of us at 90plus is the magic of Stan. He dealt with the downsides of being in comics as much as anybody.

What I see missing from your analysis (and I just skimmed the first article so forgive me if I’m in error) is Moore’s fascination with Ditko, the Question & Mr A that he outlined himself vividly in that Ditko documentary, that lead to the creation of Rorschach- a sort of fusion of the three. Why I think that ‘s significant is that character and everrybody he reacted against in Watchmen gave that story a pop, a fascination that turned what could have been something akin to the SuperFolks story into a kind of opera that sucked the reading public into it, much the same way Empire Strikes Back sizzled up the Star Wars universe into something more, or the Joker electrified the Dark Knight series the same way. Many people forget how heady & dull “Batman Begins” was though it was just kind of interesting. A character supported by characters almost as interesting and being able to understand them as a reader with pitch perfect bad guys just electrifies a plot. Even Moore himself doesn’t get to that place often. Moore is a deep guy who thinks about politics alot and what society goes along with like the tendency to romanantize fanatics who appeal to the worst in us, that’s in Watchmen too. That could be in in SuperFolks too but like I said I haven’t read it but there’s always digital.

I was just a teenager then but I remember comic shops in the late 70’s ( before moving to Monaco of course) and its bad timing when that book came out, Like just a sleepy time for a groundbreaking comic to that perhaps deserved a bigger audience to debut. Underground iin colleges is as far as it would have went. Even 10 years later with Watchmen there was more fertile ground for artistic attempts in that world with the comic press in full gear and hits abound. Frank Miller did Ronin and Daredevil a few years before, X-men was commercial and artistic hit & then there was Dark Knight and Watchmen in these limited series. Good timing and the format of Limited Series was welcome, more at its beginning. That could be it too. When it happens usually affects how it happens.

You’re wrong on the first part, as L Miller & Co Ltd never went bankrupt, but were would up in the 1970s. However, you’ll be glad to hear that we’ve finally found something to agree on in that second sentence of yours.

Well I guess we should all be thankful we have you on that wall, William.

Arse! That should be ‘wound up’, not ‘would up.’ It’s my big Irish fingers on this tiny keyboard, playing havoc with my spelling.

What’s Apple without Xerox? But then what’s Xerox without ARPA? What’s Lucas without Kurosawa? But then what’s he without the influence of Yamamoto? What’s Morrison without Kathmandu alien anal probing? But then what’s alien anal probing without the comic industry’s treatment of its earliest creators.

I mean jeez, once one starts, where does one draw the arbitrary line to stop.

Lar and Atouk first told their stories on the walls of a cave. It’s been nothing but hackery ever since.

If someone is going to venture into lit crit by accusing someone of being unoriginal, he has to do at least some “compare and contrast” to see what the purposes underlying a particular work were. WATCHMEN is renowned because Moore provided literary themes along with the other elements. If someone wants to take the quick-and-easy way to deconstructing superheroes, all he has to do is have everyone’s powers disappear. No reason required. The former heroes and villains discover that living in the real world is more difficult and frustrating than being a hero or villain ever was, and their powers and plots weren’t good for anything but wasting time on fantasies.

Writing a story that requires the reader to take superheroes seriously requires effort and skills.

SRS

The Question vs. Rorschach is a different matter entirely. This isn’t a case of inspiration. Rorschach is The Question, as all the Watchmen are to their Charlton counterparts.

Don, There’s plenty of questions that he’s “stolen” hundreds of ideas. I’m not aware of him ever being seriously accused of it outside of message boards – the biggest smoking gun anyone has ever suggested just got disproved in front of you.

What else is there? Similarity to an Outer Limits episode in Watchmen – if he stole that, it doesn’t really matter as he took a tired trope and turned it into something much better.

What else did he apparently steal? You aren’t going to bore us with his use of public domain characters are you? League or Lost Girls – both are original works. It’s not like all he did was lift characters and plonk them down next to each other and works sprung up without effort, like they would for anyone who had followed the recipe.

Is that why there’s been a renewed push from angry fans to label Moore as unoriginal – because he made fun of them for reading works derivative of his own, and made Jason Aaron cry?

I’m guessing you didn’t mention it because it’s just so obvious, but my main complaint about using “Thus Spake Zarathustra” as some sort of proof of theft is how it could be used in almost every work about superhero. It is after all the novel that gave us the phrase “superman” so any work that examines the nature of a/the superman could reference it and I’m sure many have.

I just want to put in a plug for THE KRYPTONITE KID, which I read as a much-too-young comics fan shortly after its publication. Gripping stuff, very 1970s if you are into that sort of thing. For the full effect you need to find the shiny/reflective blue hardcover, or this green-tinted paperback: http://www.amazon.com/The-Kryptonite-Kid-Joseph-Torchia/dp/0030577985

Mark: Yes, I really like The Kryptonite Kid too. A strange melancholy book. Certainly deserves a place in the list of interesting responses to superhero comics.

Filip Goudeseune liked this on Facebook.

Mark Duncan liked this on Facebook.

Hannah Menzies liked this on Facebook.

Roderick McKie liked this on Facebook.

I’ve just taken a look at the Amazon sales blurb for ‘Superfolks’ and what struck me most is how it employs the literary cachet of Moore’s ‘Watchmen’ and ‘Miracleman’ to flog Mr Mayer’s novel. In other words, we’re in the ironic position that no-one would be talking about ‘Superfolks’ today if it wasn’t for Alan Moore (possibly) appropriating a few of Mayer’s ideas into his own work. Mr Mayer talks (perhaps not entirely unseriously) of wishing he had a cut of Alan Moore’s royalties but perhaps – where the re-issues of ‘Superfolks’ are concerned at least – we should be asking ourselves if it shouldn’t be the other way around? ;)

“the influence of Monty Python’s Bicycle Repair Man on his work in general”

I feel like there have been multiple references to this sketch through the years in Moore’s work, which always seemed strange to me because it’s not *that* good a sketch or *that* funny and certainly not that well known (I’ve never seen a reference to the Cheese Shoppe, the Argument Clinic, the Ministry of Silly Walks, and can’t remember one to the Dead Parrot sketch but wouldn’t swear there wasn’t). But thinking about how it fits in with his influences, it makes a lot of sense.

“There is nothing new under the sun”

Ecclesiastes 1:9

I used to think everything was a rip off of everything else. I didn’t want to do anything creative because I could trace every idea I had back to something that has influenced me. I honestly believed I had never had an original thought in my life. Now that I’m a bit older I realise that nobody else has either. To some extent everything is fake or derivative. Embrace this knowledge and the world is yours. Just ask Alan Moore, Quentin Tarantino, The kings of Leon or any other artist of any kind who wear their influences without shame.

Comments are closed.