The second issue of Occupy Comics is coming, they’ve sent out an lengthy excerpt of a lengthier essay by Moore on Superman, comics Original Sin and more.

Excerpts from

BUSTER BROWN AT THE BARRICADES

by Alan Moore

[excerpt from Part 3]

|

|

Cover of “Spicy Mystery Stories.” December 1935. |

With the end of Prohibition during 1933, bootlegging was quite clearly no longer an economically sustainable endeavour. Printing paper, numbering among the shortages of the Depression, was apparently still readily available to the criminal interests who had until then seen publishing as nothing more than a convenient cloak for smuggling alcohol. The prurient spicy pulps, predictably immensely popular, were seen as a potential means of partly filling the financial gap left by the inconvenient demise of the illicit liquor trade. Their profitable pages swollen by occasional moonlighting Weird Tales alumni such as Lovecraft confederates E. Hoffman Price and R. E. ‘Conan’ Howard (masquerading as ‘Sam Walser’), Armer’s spicy pulps successfully negotiated moral outcries and rebukes until the early 1940s, when they finally succumbed to wartime shifts of national mood and a combined assault from legislators, censorship groups, the crusading New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, and the Legion of Decency. For some years prior to that point, however, a decline in sales and all the added nuisance of campaigns and pressure groups had meant that publishing alternatives were being actively looked into by the business interests that had turned a handsome profit from imaginative editor Frank Armer’s lurid innovation.

|

|

“Famous Funnies #1.” July 1934, Eastern Color Printing. Art by Jon Mayes. |

The controlling influence behind the Spicy titles was the colourful and somewhat shady printer Harry Donenfeld. Reputedly a former bootlegger and rumoured to be active in the publishing and circulating of the aforementioned Tijuana Bibles, it might well be thought that Donenfeld was excellently situated in a printing industry that had apparently by then become dependent on its good relations with the criminal fraternity, a necessary factor in acquiring a reliable supply of paper. During 1934 the sudden acquisition by another outfit, Eastern Color, of a significant quantity of newsprint paper, and that publisher’s attendant need for product at short notice had led to the publishing of issue one of Famous Funnies, a makeshift repackaging of various already-popular newspaper strips. This proved to be an unexpected success on the newsstands, ably demonstrating the enormous market which existed for this novel and untested format and, almost by accident, arguably establishing America’s first comic book. Pulp publishers like Harry Donenfeld, perhaps inferring from their balance sheets that the pulps’ glory days were coming to an end, were quick to spot the possibilities of this new popular phenomenon. Though they did not have access to acclaimed newspaper characters like those in Famous Funnies, it was obviously possible to generate generic copies: lacking Lee Falk’s Mandrake, one could simply substitute in-house creations like Fred Guardineer’s Zatara. Harry Donenfeld, in partnership with former union accountant, the immensely shrewd Jack Liebowitz, seized eagerly upon the comic book as his next venture on the more disreputable lower rungs of publishing. To further these ambitions, the erstwhile alleged rum-runner and pornographer first instituted the new company that would in time be known as D.C. Comics.

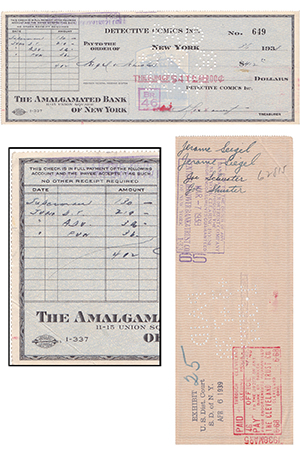

Early titles from the line, such as Detective Comics, sold robustly with their copycat array of tough detectives, comical buffoons, and the obligatory tuxedo-clad magicians, but had yet to find the killer application that would ultimately prove to be the industry’s main selling point and most reliable standby. This arrived in 1938 when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, teenage science fiction fans from Cleveland, first presented Harry Donenfeld’s formative comic business with the unique, vitalising character it had been looking for; a flagship concept that would both define and dominate the sprawling industry which comic books would very soon become. Debuting in the company’s new title Action Comics, Superman turned out to be a publishing sensation. Soon, Donenfeld’s company and every other trend-conscious pulp publisher were mass-producing vaguely paranormal characters in leotards, hoping to duplicate the staggering success of the original. Siegel and Shuster’s pivotal creation was the cornerstone of modern mainstream comics, just as the appropriation of their character by means that some have seen as dubious would seem, unfortunately, to have laid a template for the business practices which have prevailed within the comics business ever since.

|

|

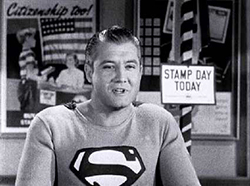

Actor George Reeves as Superman in the U.S. government film “Stamp Day for Superman.” 1954. Source/Author: United States Treasury Department. |

Reportedly finagled from Siegel and Shuster’s unsuspecting grasp when the two young men were called up to fight in World War II, their character precipitated a tsunami of costumed or masked adventurers amidst which Superman would gradually become almost completely unremarkable. However, given the predominance that Superman and the entire genre which followed him would in the end achieve, a closer look at the initial presentation would seem to be called for. Almost certainly by instinct rather than by psycho-social analysis, two Cleveland teenagers had crafted a near-perfect and iconic fantasy which spoke to something deeply rooted in the psyche of working America: propelled to Earth (and, more specifically, America) from an exploded home-world during infancy, the character, like many of his readers or their parents, was an immigrant. Then there’s the usually-unexamined matter of his humble rural upbringing, a far cry from the throng of wealthy socialites, arms manufacturers, doctors and scientists who would provide respectable and largely middle-class civilian alter-egos for the cape-clad multitude that followed hot on Superman’s red-booted heels.

|

|

Historic March 1, 1938 Detective Comics, Inc. check for $412 payable to Superman co-creators Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster. In addition to other services rendered, the check includes a $130 line item for ownership of Superman. As Superman rose in popularity to icon status, Siegel and Shuster’s careers faltered. They embarked on a failed lawsuit to regain ownership of Superman, and in the settlement were forced not only to relinquish all rights to the character but even lost the basic right to credit themselves as Superman’s creators. |

At his inception, Superman seems very much a representative of the downtrodden working classes his creators hailed from, and a wonderful embodiment of all the dreams and aspirations of the powerless. Dressed in bright primaries where most of his Depression-era readers were confined to threadbare black, or brown or grey, here was a character that in a single bound could leap above the worn-out city streets which his impoverished countrymen were forced to trudge in search of work. While the ensuing decades and expanding fortunes of America have seen Siegel and Shuster’s purloined champion recast as an establishment ideal, a figure that embodies tactical superiority and thus perhaps a sense of national impunity, the archetypal superhero at his outset was a very different proposition. In his earliest adventures, with an admirably broadminded definition of what constituted criminality, a splendidly egalitarian Man of Tomorrow would rough up strike-breakers and use his super-strength to hurl unscrupulous slum landlords over the horizon. Gradually across the next few years, perhaps in keeping with the Cleveland pair’s decreasing power to control their own creation, Superman would undergo a moral and political makeover to become a bastion of authority, carefully trimmed of any prickly or non-conformist attitudes.

This same trajectory is to be seen in many of America’s pop-culture icons, such as the initially demonic and yet rapidly suburbanised form of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse. If, as suggested earlier, American identity first bonded and solidified around the nation’s entertainment industries, we can perhaps see why this taming process was considered necessary. Symbols which enshrined America’s emergent image of itself were simply too important socially to be left in the hands of unpredictable and sometimes idealistic individuals such as their creators. Clearly, it was seen as more appropriate for these new U.S. totem entities to be in the possession and safekeeping of frequently questionable businessmen rather than that of the genuinely talented and decent human beings who’d originated them. Given that Superman had been rebranded as exemplifying Truth, Justice and the American Way, it seems ironic that the first two of these qualities had been so casually dispensed with, while to judge from the behaviour of the nascent comics industry it would appear that their interpretation of ‘the American Way’ had little to distinguish it from any other forms of spineless underhand deception, larceny or bullying.

|

|

According to Craig Yoe in his bookSecret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-Creator Joe Shuster, Superman co-creator Joe Shuster anonymously illustrated likenesses of his Superman characters being beaten and tortured in the fetish comic book series “Nights of Horror” after he and co-creator Siegel lost rights to Superman and its related characters. Many believe these illustrations channel Shuster’s rage at losing his creations. 1950s.

|

The industry’s apologists have offered various glosses for the shameful act of theft upon which the vast business that supports them seems to have been founded. One of the more despicable of these constructions has it that Siegel and Shuster should have been more shrewd in signing contracts, which appears to be a variant on the well-known American proverbial advice regarding suckers and the inadvisability of giving them an even break. More lately there have been attempts to mitigate the industry’s offence with an appeal to half-baked mysticism and postmodernism, maintaining that Superman and the commercial children’s comic characters which followed him are all in some sense archetypes that hover in the ether, waiting to be plucked by any lucky idiot who passes by. Ingeniously, this sidesteps the whole Siegel and Shuster problem by insisting that creators in the superhero field aren’t actually creators after all, but merely the recipients of some kind of transcendent windfall fruit that should be freely shared around. Even if this were true, it’s difficult to see exactly how it justifies a perhaps gangster-founded company of fruiterers (just to continue the analogy) declaring that these profitable magic apples all belong to them in perpetuity. Still, one can see why such a morally-evasive brand of metaphysics might appeal to the large corporate concerns which steer the comic industry; to those amongst the readership whose primary allegiance is to a specific superhero rather than the ordinary non-invulnerable human who originated him; and to those loyally and profitably labouring at franchises, who know they’re in no danger of ever creating an original idea which would be valuable enough to steal. Alternatively, those not found in the preceding factions might question the wisdom of erecting such an important commercial and ideological endeavour on foundations so blatantly rotten and so lacking in the necessary load-bearing integrity.

[related excerpt from Part 4]

Unfortunately, being seemingly reluctant or incapable of altering the seamy and disreputable practices of comics past, the publishers were raising their immaculate new edifice upon foundations that were riddled with decay. Despite the fact that the array of publishers and editors who steered the comic industry did not themselves appear to possess any noticeable talents save for cheating the more gifted out of their creations, hustling, and otherwise accumulating money; and despite the fact that lacking an exploitable parade of artists, writers, and just generally creative individuals the entire industry, the superhero, and the new house that the publisher just bought would not exist; despite these things the comics business would continue to routinely bully, cheat , abuse, and alienate the very people on whom it depended. Comic book concerns and businesses, gangster initiated, casually applied the values and techniques of their illustrious founders, treating their creators with a breathtaking contempt as if they saw the men and women who had made their fortunes as plantation slaves or some variety of fuel-rod, endlessly replaceable and therefore instantly disposable. Regrettably, a sizeable proportion of the industry’s creative individuals would seem to have internalised this image of themselves, perhaps through lack of confidence in their marketability without the proven lure of the established superhero franchises which they are working on, and have remained content in uncomplaining loyal servitude until age compromises their abilities and they’re inevitably cast aside by their employers.

Amidst the vast multitude of cowed, intimated workers on the comic book assembly line, only those rare creators with a sense of their own worth have ever actively defied or walked away from their tormentors. Unsurprisingly, these turn out to be by and large the same creators who have done most to enrich the comic world. Siegel and Shuster, from a very early stage, were public in their anger over having been deceived and cheated out of Superman and its related properties, though it was not until the groundswell of publicity surrounding the first Superman film in the 1970s that, largely through the tireless work of, arguably, the real Batman co-creator Jerry Robinson, D.C. were shamed into allowing Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster a small pension as a thank-you for creating the whole superhero industry. That this begrudging stipend was inadequate is evidenced by the long-running lawsuit which Siegel and Shuster’s families have served upon D.C., a lawsuit one suspects to be the reason why a television show that could quite reasonably be expected to be titled Superboy has instead aired as Smallville. It is safe to say that many of D.C.’s revamping efforts with the character, along with their apparently coincidental drastic overhauls of continuity, are predicated not on any true creative reasons but upon the possibility of losing ownership of certain concepts, brands or characters in an ongoing legal battle that is only now approaching its hopefully just conclusion.

Superman’s creators, obviously, aren’t the only talents in the comic business to have raised objections to their treatment. In what can be seen as both an admirably heartfelt and almost poetic statement, the creator of the 1940s Human Torch and thus of the first Timely/Marvel superhero character, Carl Burgos, took his comic book originals out onto his front lawn and torched the lot of them. By the middle-to-late-1960s both Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby, tired of being kicked around by Marvel after all that those two legends had done to create the company, jumped ship and went instead to work at Charlton or eventually D.C., where one suspects that they fared little better. In Jack Kirby’s case, as with Siegel and Shuster, Kirby’s family are engaged in an ongoing legal contretemps with Marvel Comics over ownership of all the characters that Kirby undeniably created. Given that no-one at Marvel Comics wants to contemplate what all its movie franchises would look like with the Kirby characters removed, it may well be imagined that the full might of their law department has been marshalled to prevent this nightmarish scenario from occurring.

Read more in Occupy Comics #2…

Longwinded with little original content. And he’s got a nerve complaining at anyone “maintaining that Superman and the commercial children’s comic characters which followed him are all in some sense archetypes that hover in the ether, waiting to be plucked by any lucky idiot who passes by.”

….Interesting that he left out Neal Adams’ role in getting Siegel and Schuster their royalty…

Joe – have a read of Supergods.

Superman is a children’s character, when written as a hero. His power set is a fantasy, his motivations are pure and simple, and he’s written as a symbol. If his motivations become complex, due to the issues he’s dealing with being complex, or balancing his self-interests against the interests of others, then the details of the character have to make sense on an adult level. Making sense of his biology would be difficult to impossible, because he’s an alien and invulnerability is practically impossible to justify on the cellular level. He’s a bag of chemicals, like humans are, and chemical interactions govern biochemistry. If the writer decides to skip the details, then how does one write him for adults?

Probably the only way to do that is to reason what the life of someone like Superman would be in the real world. It would be hell for someone with even a fraction of his power set: endless demands on his time and no way to satisfy them all. If he couldn’t find a way to give others similar powers, the best thing that could happen to him would be to lose them.

Superman is so simple that the number of stories that can be done about him, as a single character, without the writer repeating himself, is small. If he’s in a superhero universe, the number of possible stories increases, but if the existence of the other superheroes isn’t justified, then all the heroes are children’s characters again.

SRS

I do enjoy Moore’s writing when he lets rip on a subject he’s passionate about. A comics history from him in book form would be tremendous.

That said, I get the feeling that this is tinged heavily with his dislike of contemporary commercial comics which is not entirely justified, though I do agree that the ever present tension between corporate publisher and created superman renders the latter somewhat mute ethically and morally.

I do think Siegel and Shuster were screwed over, and I do think that many creators after were (and are) treated similarly. I’m not 100% sold on the originality of Superman as a concept rather than character though – surely he is simply a new form of Jesus, Horus, Attis, (Glycon!), with measures of Apollo and company, Appleseed, Robin Hood and more. S&S were treated abysmally for their creation and I don’t intend to diss them here, but with the various pulp heroes of the time and coming out of the Depression/into the war, was a super man of some description not inevitable?

Brits like Alan Moore and Grant Morrison always read too much class stuff into Superman. If you actually read the original stories he either gets corrupt rich people to reform their ways or gets them tossed into prison if their crimes were intentionally evil rather than just negligent or uncaring. He never actually redistributes any wealth. Guess it’s hard to take your own cultural blinders off sometimes.

And Superman himself is something of an amalgamation of Philip Wylie’s super being from the novel “Gladiator” and a large amount of the Doc Savage mythos. This is pretty standard procedure for most super-hero comics. Green Lantern is Lensman, Punisher is Mac Bolan, X-men were ripped off the novel “Children of the Atom,” etc, etc.

“More lately there have been attempts to mitigate the industry’s offence with an appeal to half-baked mysticism and postmodernism, maintaining that Superman and the commercial children’s comic characters which followed him are all in some sense archetypes that hover in the ether, waiting to be plucked by any lucky idiot who passes by. Ingeniously, this sidesteps the whole Siegel and Shuster problem by insisting that creators in the superhero field aren’t actually creators after all, but merely the recipients of some kind of transcendent windfall fruit that should be freely shared around. Even if this were true, it’s difficult to see exactly how it justifies a perhaps gangster-founded company of fruiterers (just to continue the analogy) declaring that these profitable magic apples all belong to them in perpetuity. Still, one can see why such a morally-evasive brand of metaphysics might appeal to the large corporate concerns which steer the comic industry; to those amongst the readership whose primary allegiance is to a specific superhero rather than the ordinary non-invulnerable human who originated him; and to those loyally and profitably labouring at franchises, who know they’re in no danger of ever creating an original idea which would be valuable enough to steal.”

Just because these remarks have negative implications for Moore’s own brand of mysticism doesn’t make them any less important and cutting.

>> S&S were treated abysmally for their creation and I don’t intend to diss them here, but with the various pulp heroes of the time and coming out of the Depression/into the war, was a super man of some description not inevitable? >>

I have no idea whether such a character would be inevitable or not, but it doesn’t make the creation of Superman any less an act of creation.

One can argue that Frankenstein has plenty of mythic predecessors, including the golem and God’s creation of Adam, but that doesn’t mean that Mary Shelley didn’t create something that has had lasting appeal and power. Having predecessors and inspirations does not mean that what you make out of them — and your own additions — isn’t new.

“Transcendental windfall fruit”– that’s a clever line. I fully agree that even though no archetype belongs to any one person, the particular iteration of a given archetype certainly does begin with a particular creator or set of creators. That’s an important part of history, though we should remember that Moore has asserted that creators’ rights end with the creators’ deaths, after which he’s clearly stated that other authors ought to be able to “steal” them.

Nevertheless, Moore’s earlier argument re: the lack of shrewdness of S & S is worthless. They tried to wangle a short-term deal on a character they hadn’t been able to sell for years. No amount of sniping at the mob ties of the early DC honchos changes the fact that these creators made, even for the time, a really bad business decision. The mob ties are especially irrelevant in that DC did live up to the letter of the law with regard to relatively well-executed deals by Bob Kane and William Marston.

And yes, I know Kane used some legal chi-Kane-ry. But DC still did well by him. The neglect of his colloborator Bill Finger I lay more at the door of Kane than of DC.

For more on work for hire, from the freelancers viewpoint, I posted the following which includes links to commentary by NCS President Tom Richmond, Steve Bissette , Superman piece by Steve Gerber, Life after Marvel by Herb Trimpe and much more. http://www.jimkeefe.com/archives/3371

“Just because these remarks have negative implications for Moore’s own brand of mysticism doesn’t make them any less important and cutting.”

You know what does? The fact they’re addressing an argument THAT NO ONE OF ANY IMPORTANCE HAS EVER ACTUALLY FUCKING MADE, with of course the exception of a certain bald comics writer for whom Affable Al has a pre-existing hate boner.

“Moore’s earlier argument re: the lack of shrewdness of S & S is worthless. They tried to wangle a short-term deal on a character they hadn’t been able to sell for years. No amount of sniping at the mob ties of the early DC honchos changes the fact that these creators made, even for the time, a really bad business decision.”

For people so absolutely certain of their moral righteousness, a lot of S&S’s defenders seem absolutely terrified that any kind of nuance – Like, say, acknowledging that after that initial $130, DC went on to pay S&S for further Superman material over the next few years with amounts that in today’s dollars would be pretty hefty sums – will shatter their case. S&S, and their families, have plenty of real, legitimate legal, financial and moral arguments to make against DC. But they tend to require thought and research to understand, and hence are repeatedly rejected in favour of ridiculous fairy tales about a couple of wide-eyed innocents wandering into the big city and encountering a bunch of mobster fat cats who can somehow instantly tell that their big idea will earn billions of dollars over the next 75 years, and so snatch it away, press a shiny quarter into their hands in return, then kick them out of the building forever before going off to twang their braces, drink port and set light to comically over-sized cigars with burning hundred dollar bills.

“Having predecessors and inspirations does not mean that what you make out of them — and your own additions — isn’t new.”

Kurt Busiek – indeed, but I was referring more to the idea of them being ideas plucked from the ether – that had S&S not come up with Superman, something similar would have filled the gap. It doesn’t mean Superman isn’t new, I was just pondering aloud on that particular argument as I think it’s a little more nuanced than described here.

“That’s an important part of history, though we should remember that Moore has asserted that creators’ rights end with the creators’ deaths, after which he’s clearly stated that other authors ought to be able to “steal” them.”

gene phillips – that’s kinda the problem with creators taking a stand on creators rights a lot of the time – it can sometimes mean “apart from what I deem acceptable”. I’m not saying that is what Moore is doing, but it’s difficult to assume a position of moral superiority when doing something that is perhaps morally questionable yourself in a similar direction… That is to say, we are all just people and therefore all a bit of a bastard at times.

Great editing job by Hannah Means-Shannon! Can’t be easy editing Mr. Moore!

“Kurt Busiek – indeed, but I was referring more to the idea of them being ideas plucked from the ether – that had S&S not come up with Superman, something similar would have filled the gap. It doesn’t mean Superman isn’t new, I was just pondering aloud on that particular argument as I think it’s a little more nuanced than described here.”

Even if something else would have filled the gap, that doesn’t mean the screwing of S&S was morally justified or was something less horrible than it was.

I think that’s why some people don’t like that argument, it’s subtle purpose, whether the person making it knows it or not, is to make what S&S creation to be something not as special as it is and the greedy actions of the publishers somehow not as bad.

I also think it’s dumb to take Superman’s appeal for granted. Something similar might have been created, but depending on the character, the stories, the origin, the artist, etc.. it might not have been anywhere near as popular.

See the new Superman flick and then read the free Superman #1 on Comixology and you’ll realize just how right Moore is. Superman is dead; his corpse possessed by Satan.

Comments are closed.