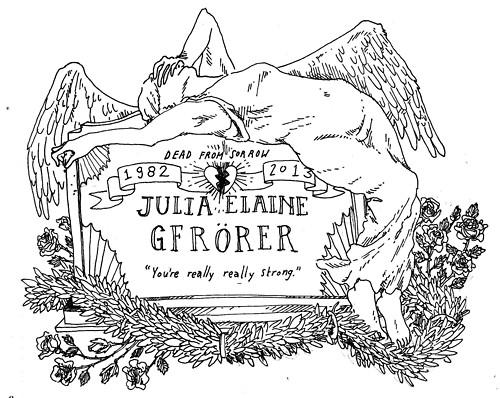

One of the advantages in writing for The Beat is the opportunity to provide under-appreciated comic creators with a platform, to share work which genuinely excels, work which excites you. This interview with Julia Gfrӧrer, whose comics and art work I have been a fan of ever since I came across it over a year ago, was one of the first things I began putting together, in the hope of making more people aware of the fantastic comics she produces. There’s a difference between being a favourite creator and a best creator; Gfrӧreris the level of good that she inhabits a place on both.

I discovered her work at a time when I was just beginning to explore comics and all they could be more widely, and its existence affirmed both my passion for medium and the belief that it encompasses more than we know. If the time I’ve taken in order to do both her art and her responses justice pays off with even a few people buying her work and checking it out, then I’ll consider this a very successful undertaking. But let’s start at the very beginning. How did Gfrӧrer get into the whole comics thing?

‘My route to comics was less than direct. Growing up, I did a lot of reading, writing and drawing. I made zines in junior high and high school. For most of my life I was very serious about becoming an Egyptologist, but in my late teens I began suspect I was no true intellectual, so I went to art school and majored in illustration because I wanted to learn to draw really well, with no thought to my future career.’ After her sophomore year, she decided to switch to a fine art major and graduated in 2004, with a BFA in painting and printmaking, with comics still not really on her agenda in any significant way. She pushed on though, showing her work in galleries, applying for grants, making a few minicomics on the side and doing ‘whatever a fine artist does.’

It wasn’t until 2007 when she moved to Portland (where else!), that hive of comics and art creativity, that her art began to find a more solid affinity with the medium. ‘I had just made a mini called “How Life Became Unbearable,” about Saint Francis of Assisi. I took it to Pony Club Gallery to consign it, and that was how I met Dylan Williams, who was a member then. Around the same time, I was in a show at Launch Pad Gallery, and I was doodling a little comic at the opening, and Sean Christensen zeroed in on me like I had flashed the comix beacon. So those guys were my first friends in my new city, and they introduced me to their friends and encouraged me to be part of their projects, so before I knew it comics were my whole world.’

She acknowledges the clumsy Hans Christian Anderson comparison I suggest; thematically they share an affinity for the twisted and romantic, but where Anderson’s stories usually end with a full-stop, Gfrӧrer’s are punctuated with question marks. She doesn’t think the comparison extends beyond those similarities: ‘Anderson and I have some common interests, most obviously an ideology that romanticizes suffering, self-sacrifice, and death, so that seems like an apt comparison. But virtue and physical beauty are kind of meaningless to me, and romantic love without an erotic component seems like sacrilege, so there we differ. I think we owe it to creators we admire to try to appreciate their work on its own terms, so I look a little askance at modern reinterpretations or deconstructions of classic literature, with contemporary aesthetics and morals tacked on. That’s not a strict rule, there are works of art I like that could be said to take that approach, but I’d be cautious about doing it myself.’

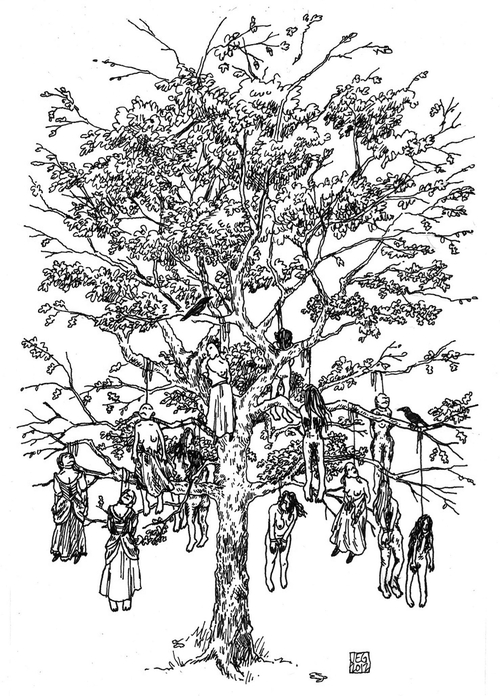

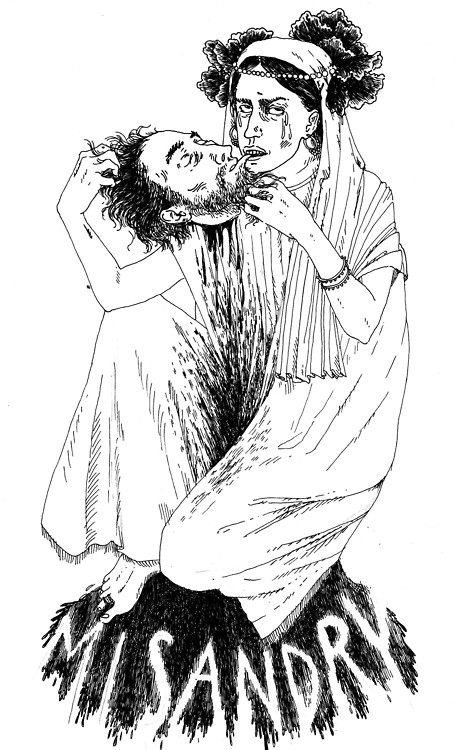

There are, however, common threads and themes that run through Gfrӧrer’s work; superficially these can be tagged and labelled as sex, or horror, death, the murkily ritualistic, the transcendent, and generally elements aligned towards the darker, unknown aspects of life. But her work resonates with the reader because it succeeds in harbouring a greater depth- ostensibly it explores humanity: people and their wants and desires, their extents and extremes, their complex simplicities, and always coming from a place of such feeling and emotion; the crux of what drives anyone to do anything, the crux of being. It’s made all the more stronger by a tangible, focused essence lent to it by its creator, and Gfrӧrer’s willingness to explore herself, her emotions, things that trouble or interest her, and spin all that into a true fiction laid out on the page, ‘For as long as I can remember I’ve used drawing as a way to manifest my darkest thoughts: if it scares me, if it makes me cry, if I feel ashamed for thinking it I’ll try to put it on the page and address it. I want to hunt my demons down and ride them until they die of exhaustion.

There’s a confrontational element to my stories, though my drawings tend to be, despite my efforts to the contrary, very delicate, and I think I’ve only been able to get those elements to work well together in an intimate medium like a book. Maybe it’s just that I feel safer spilling my guts into a book, which, in a sense, receives its audience in private.

I wrote a comic last summer about Athanasius Kircher taking me on a tour of the world underground, and when I’m afraid to go he tells me, “It is the duty of those who possess even a little courage to explore the world within, and to map it for those not destined to explore.” Without meaning to, I was writing my mission statement.

A “mythical” story conveys emotional truths more precisely than a story based in quotidian fact, so I try to discuss, using symbols, experiences that are otherwise difficult or impossible to depict. Pain is like a star that only appears in your peripheral vision: I can’t show it to you explicitly, but I can say, “It’s to the left of this, it’s a little above that,” I can describe some coordinates in the form of a myth, and hopefully when you read the story you’ll know where to find it.’

I ask her about a response she gave in an interview for The Comics Journal a few years ago, in which she said:

I have a morbid fascination with the indignity inherent in being alive, the reality that our bodies are so demanding and that they are constantly, continuously betraying us, getting in the way of all the really meaningful things we could be doing instead, yet occasionally communicating nobility with their involuntary actions.

I find that pretty interesting, I say, because I’ve always thought the opposite: that it’s the mind that holds us back, and our inability to overcome our mental barriers keeps us from freedom. ‘In that (the TCJ) response I described the needs of the body in negative terms, in contrast with the relative freedom conferred by death, to explain why death is frequently treated as a happy state in my work. But I don’t necessarily value the truths of the inner world, of the mind or the soul, more highly than I do those of the body and the physical world, and neither, in my opinion, has a higher claim to freedom.

What interests me is that there are many worlds which constitute “reality,” and they don’t necessarily have a strong relationship with one another. You could love a woman, and the woman could love you back, and she could be a character pillow, and a pillow can be unable to feel, nor can a pillow be a woman, all those things can be simultaneously true though they contradict each other: if the lover’s experience of the pillow is that the pillow loves him, who can say he’s wrong? The inner world may or may not be compatible with material reality, though it is no less valid, and that is a dilemma I address in almost everything I make, and I never seem to grow tired of it.’

Perception, truth, reality, spirituality and transcendence- another thing that sets Gfrӧrer apart (and is reinforced from interviewing her) is her intelligence. It’s present in, and elevates her work, and it’s clear how much thought she puts into creating her art- and not in a studious, deliberately enforced manner- ‘this story will be about this, and say this and mean this,’ but in that her narratives are organically enmeshed with thoughts, ideas and questions. Her comics are entertainment, a presentation and an enquiry.

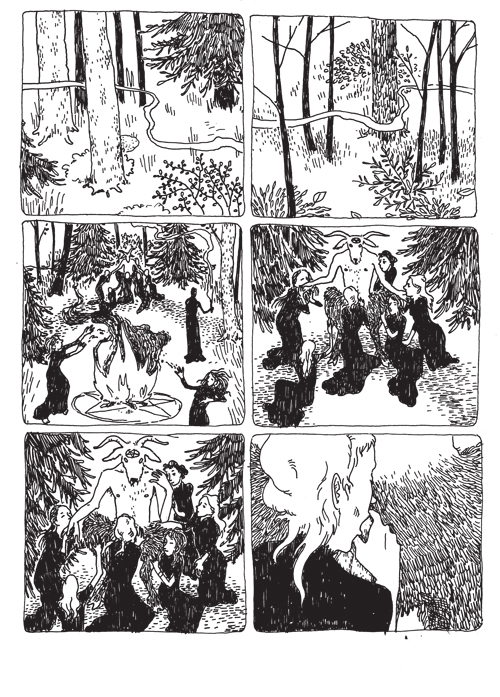

Take Flesh and Bone, for example, a Gfrӧrer mini-comic from 2010, a period tale of a man who, lost in the grief of his dead wife, determines to get her back in some shape or form and at any cost. She takes the prevailing powers and influences of the time- the tensions between religion, witchcraft and mysticism and the natural world and combines them with a story about loss and grief and blood and sex, the blending and differentiation of need and want and desire, that not only do you engage with, but involves you more at every turn- is he right in taking this course of action? How does it make you feel (because it WILL make you feel)? What would you have done? Who is right? How far would you go?

Quite a few of her comics are set in times gone by- does she find it easier to have that remove with the more ‘controversial’ subjects she writes about? ‘Usually I start out with the spine of a story fixed in my mind, and as it gets fleshed out it just seems to fit better in one time period or another. For example, Flesh and Bone wouldn’t make sense in a contemporary setting: the public masturbation, the extreme religious paranoia, the accessibility of the execution site, the disappearing children, all those things would require an explanation, but in a historical fairy tale rural setting they seem reasonable enough.

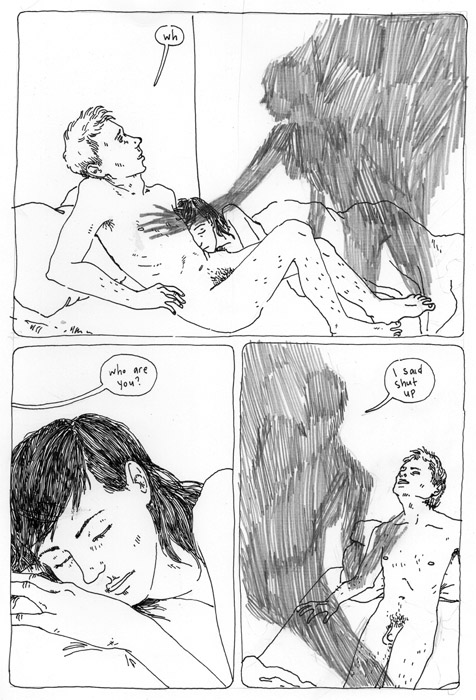

On the other hand, a story like Too Dark to See wouldn’t really work in a historical setting because the class/gender/identity angst that drives the plot would feel anachronistic, and because the audience needs to take for granted that the characters won’t consider a supernatural explanation for their problems. In fact the audience should disbelieve, as the characters do, that the supernatural things in the story are “real,” even though they’re obviously present–people come away from that story asking me whether the shadow people are really there, or are they just a symbol? Nobody asks me whether the witchcraft was real in Flesh and Bone.

I like writing for a contemporary setting, but a contemporary mermaid story would be kind of a hard sell, it feels unpleasantly whimsical to me, so for that reason Black is the Color had to be set in the past. That, and I had just bought a book at the thrift store about the Golden Hind, and I really wanted to use it as a reference.’

Visiting the odd and disconcerting is something Gfrӧrer does regularly, often placing the reader in an uncomfortable position –that confrontational element coming into play again: where are you going to stand? In these disturbing vistas, does the reader attaching themselves to a character, thereby accepting he relates to or recognises some aspects of himself on the page, or does he instead take up the position watcher, voyeur. watcher. It’s excellent story-telling, never overt or leading and a conscious technique on her part- she wants the reader to be uncertain almost, to be questioned and thoughtful, to explore with her. ‘Anytime a story I’m working on begins to feel didactic, I know I’m doing something wrong. I really resist telling the reader how to feel, force-feeding them ambient trivia, indoctrinating them to my personal philosophy, or in any way presenting them with something that resembles a story but is actually a self-important lecture. I’m happy to drop self-important lectures almost anywhere else (like here, for example), but I’m not Jack Chick, so I try to avoid them in my art. If I were sure of how to feel about something, you can bet I wouldn’t be making art about it.

It’s important to me personally to nurture the moral gray areas, rather than forcing them to conform to an arbitrary dichotomy. Areas of uncertainty are very attractive for me to write about, not with the intention of clearing up the uncertainty or of forcing readers to confront it, but mostly because like many artists, I’m insatiably curious, and I enjoy being afraid: the more unsolvable the mystery, the more time I want to spend with it.’

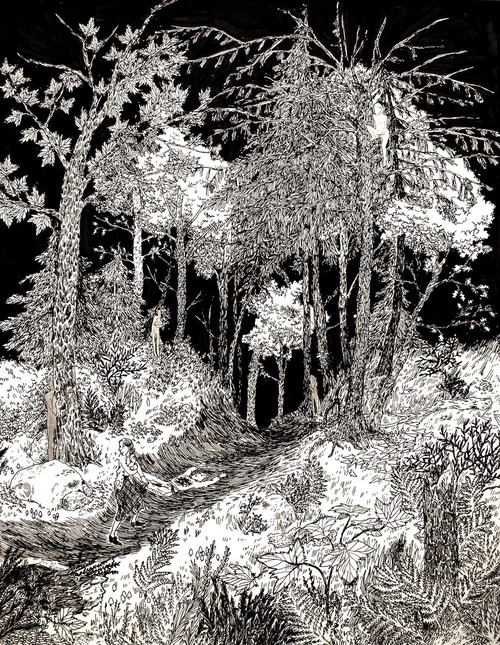

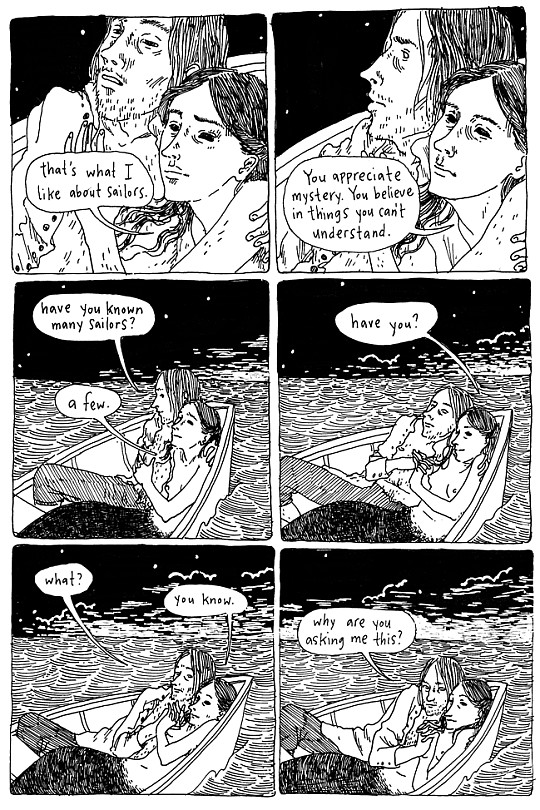

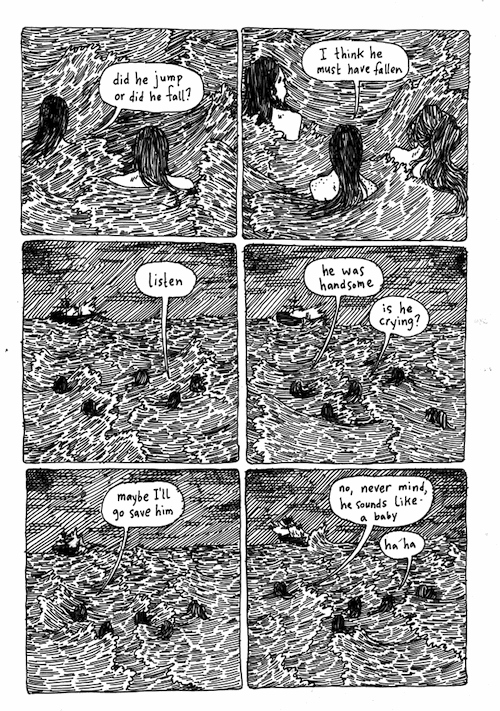

Gfrӧrer’s work seemed to take another step up last year via the serialisation of her excellent online comic, Black is the Colour, hosted by Study Group Comics. It’s the tale of 2 sailors who are put into a little wooden lifeboat when the ship’s Captain decides he has more mouths than he can feed. It’s a mermaid story on one level,and one unlike anything else you’ll read. Gfrӧrer’s art, always delicate, fine-lined and viscerally juxtaposed against her narrative, worked its magic on a whole new level, rendering the ocean’s waves, the deep skies, the increasingly gaunt sailors, the hungry, cruel beauty of the mermaids- there’s a melding of form and content and style that marks it as a singular, brilliant piece of work. It also led to her first publishing deal with Fantagraphics, ‘Jason T. Miles has been a friend for awhile, and he had been really supportive of my work, so when I started working on the book I called him up to offer it to Fantagraphics, we kept in touch as I was working on it, and when it was complete they sent me a contract. When I found out it was a definite thing, I cried, I was so happy.’

Did she find having the story syndicated on the Study Group website helped more than hosting it on her own site, in that it was accessible to a larger audience, and being her longest work to date, gave people the opportunity for investment? ‘Serializing it on my own site wasn’t an option. If it hadn’t been published on Study Group, I would have eventually just drawn it in private and found a publisher for a print version of it when it was complete.

I had scripted/thumbnailed the story in late 2010, and kept it more or less in the vault until spring 2012, when Zack Soto asked me if I wanted to do a serialized story for Study Group. I offered him a handful of different story ideas, and that was the one Zack picked, so I started drawing the final pages. Most of the time I was working at least a week or two ahead of schedule. There were a few scenes that were very time consuming to draw–the electrical storm on the ocean in particular–and a couple of times I finished the pages and sent them to Zack the same day they were published online.

I was and am very emotionally invested in the story, though I don’t know that I could say more so than previous books. Its length was important, though, because more than any other comic I’ve written, it is a story about loneliness, the sense of vastness and dread needed space to develop, so it was important to slow it down, and make it roomy, which in comics can be much the same thing. Black is the Color includes many, many luxuriously silent panels where nothing happens. Publishing it on the web certainly gave me the opportunity to put in as many of those as I could stand to, without worrying about a particular page count. Looking back at it now I almost wish there were more of those very slow-blooming scenes. The final scene could have been five times as long, with one of those dead whale ecosystems. Maybe I will add that, actually.’

It seemed to strike a chord with readers, too, gaining positive write-ups on various sites. There’s still, to my mind, a significant and marked lack of sex in comics, and certainly very few people who use sex as one of the lenses through which to examine life, people and meaning. I wondered if the less graphically explicit nature of Black is the Colour (when compared to some of Gfrӧrer’s other work) has perhaps made it more approachable to a wider audience. Gfrӧrer disagrees. ‘I think in many ways Black is the Color could be considered less accessible. Compared to my previous work, there’s very little action in Black is the Color, and the drama that does occur kind of relies on the reader following a series of slow-building emotional cues. Although it is probably safely in the R range, visually, rather than the NC-17 of my earlier books, in some ways it might require an even more mature audience. I wouldn’t want anyone reading this to get the impression that Black is the Color is, like, my “soft” book. It is as gross as anything you’ve seen from me previously, just more subtle.

Most depictions of sex in comics are so painful to read: they’re insulting to women, they lack pathos, they’re banal. No doubt the way I compose a sex scene is, at least in part, a reaction against the more clinical depictions I’ve been frustrated by in the past. I try talk about sexuality in a way that feels both truthful and erotic to me, that reflects my actual experience of sexuality, which means being ruthless in including whatever baggage is necessary to that end. Apparently the point at which those qualities converge is one where comics have rarely taken root, because I get asked about it a lot.

It’s hard to answer this, because I write about sex for the same reasons as any writer: it’s aesthetically exciting, and it’s necessary to move the story forward. I don’t include it intending to make some kind of point. I kind of don’t get why people write stories without sex in them.

If anybody has been grossed out by the sex or violence in my earlier books I have yet to hear about it, either because indie comics readers are thick-skinned, or because people who feel that way are afraid to talk to me about it. Which is great, because I don’t want to hear about it.’

I like to ask people who their favourite comic character is, as a way of signing off interviews, and I’m initially surprised when she offers up Japanese horror master Junji Ito’s Tomie, but it’s the perfect Gfrӧrer choice, really, as she explains, ‘She’s the most poetic critique of the social construction of femininity that I’ve yet seen in comics. I don’t know that she was written with that intention, but her character is so well-drawn that a fantastic premise plays out in a way that feels painfully real. She’s seductive, mysterious, eternally youthful, playful, and voracious, but she’s also dependent and insecure, competitive and jealous, she’s a hideous monster, her body is out of control, she hates herself. In a sense, she is exactly what patriarchal culture expects women to be, and her story is a horror story. I love her. My friend Sean loaned me the books last summer and I kind of lost my mind over them.’

Julia’s website: www.thorazos.net

Julia’s Tumblr blog

Buy Too Dark to See here

Buy Flesh and Bone here

(A huge, huge thank you to Julia for all her time and patience in doing this interview and seeing it come to print- of sorts)

Interesting stuff. Although I suspect the reason one doesn’t see a lot of sex in comics is because publishers are trying to appeal to the masses and a younger audience or are too afraid that they might offend but comics dealing with sex, and not always as the focus of the story, are out there if one looks. But certainly, more comics dealing with the subject in a mature way should be welcomed for a mature audience.

Thanks for the article and introducing me to this creator.

@Shark Jumper

I think the only publishers who are actively pursuing a broader public are Top Shelf and First Second(and to a much lesser extent Marvel). The others have a really specific demographic that they are mining and it usually consists of older men.

Comments are closed.