To answer your question, no, I am not done with superhero comics. I surely love me those heroes. But the next thing will take a little time. Past superhero series I’ve been involved with had too many captains trying to pilot one boat. Characters taken from me mid-story. Plots imposed from above, and then changed arbitrarily. That’s no way to tell any story well. So the next project will be one I create from the ground up and control fully. No more begging permission from distracted gatekeepers.

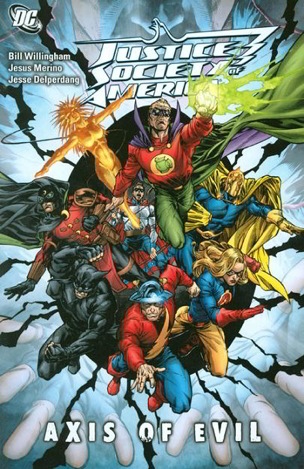

It wasn’t just a matter of characters taken away for big crossovers and such. I had one character, Liberty Belle, taken from my JSA……to join the JLA — but no one told me. I learned far after the fact from @matt_sturges who read a script of mine and wondered why I was still using her in the JSA. Call from editor? Nope. Call from fellows who took her for the JLA? Nope. Silly way to run a circus.

Yeah, Shadowpact was another example of abrupt changes made constantly to stories that had been approved for months…… starting with 1st page of 1st issue, and never letting up. Too bad. I had hopes for the series too.

Don’t get me wrong. I think work for hire is a reasonably fair system, provided you know what you’re getting into. But to hire a fellow to write a series, approve the stories, but then do everything possible to disrupt and derail those stories seems odd.

No editorial hasn’t increased over the years, they’ve gotten (at least in one house) more chaotic. Today’s idea supplants yesterday’s idea! Now, everyone implement the changes on the fly! Hold on! We just had a new set of ideas at lunch! Everyone get ready for new changes! No I will not list all of the changes required for any series, only because it would be too long a list. But to say changes were called for on every page of every issue wouldn’t be an exaggeration.

Willingham still enjoys his FABLES experience, however:

Good question. On Fables there is editing, well in advance of production, but never last minute whim changes required. And no one at DC can grab Fables cast members, without my say so, for other stories. That’s the job of big TV networks.

Yesterday, Willingham had tweeted:

Fables is # 1: tinyurl.com/3z87sf6 Suck on that, two TV networks with Fables-esque series coming out soon (not bitter, but prepared to be).

in reference to Once Upon A Time, an ABC show about fairy tale characters trying to break an evil queen’s curse.

At the SDCC Fable panel, Willingham mentioned Fables had been shopped around to many tv networks and movie studios. He said in their wake many illegitimate babies were left behind, of Fable-like projects being worked on without them actually using the Fables licensed, since all the characters used are in the public domain.

Whenever a bad story appears in a publication, an editor or editors can be blamed, can’t they? The editor is ultimately responsible for the quality of the stories he publishes.

An editor should have all the capabilities of a writer, or he won’t be able to recognize and fix problems — and the earlier a problem is recognized, the better. Making changes in a story or series without detailed explanations is terrible, and I doubt that a writer would want an editor to suggest story ideas, character ideas, etc., without being asked for them.

SRS

Synsidar — reactions don’t tend to flow logically, I don’t think.

An editor CAN be blamed, but aren’t often. Mandated ideas or changes almost always come down to the creative team, when blame is concerned. (To be fair, the same is true of praise.)

While a few hardcores may, for example, single out Steve Wacker for something having to do with Spider-Man, more likely you’ll hear “God, Slott is ruining this book” or “Slott saved Spidey for me, yay!”

…No matter how many good (or bad) ideas were brought in by editorial mandate.

I’ve heard a few horror stories too; big 2 stuff, editorial weirdness, creative team bearing the brunt of fan reaction. Some of the stories are pretty funny, but not mine to share.

I love how he doesn’t name the “house” with the ADHD problem, but it’s patently obvious to anyone with a smidgen of industry awareness.

Since we’re talking about editors, here’s a throwback to one of Mark Millar’s old columns, “The Seven Types of Comic Book Editors.”

I found it insightful, especially this line:

“How to get INTO editing is something I just don’t know. Whether it requires English degrees or cock-sucking skills, I just can’t say, but I’m inclined to think that it’s a combination of both.”

Sorry, the Time Sphinx jumped before I could add the link:

http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=14308

“Whenever a bad story appears in a publication, an editor or editors can be blamed, can’t they?”

Not necessarily. Depends why the editor ended up running it.

I mean “bad” to be a story with a defect or defects that ruin it. A good story can have cosmetic glitches which don’t eliminate its impact — a typo doesn’t negate an argument in an essay. With a bad story, the reader and the serial characters in it would have been better off if the story hadn’t been written.

Roy Thomas was responsible, in large part, for the good stories at Marvel in the ‘70s, because he let good writers do the stories they wanted to do.

I’d hope that, given how comics are produced, that the creators’ work is approved at several stages: the basic story idea, the working plot, the script, and (bunches of) pages as they are produced.. That should eliminate serious problems. If the editor does less than that, the creators involved should be very trustworthy.

SRS

The reactions to Morales as Spider-Man reinforce the point that many readers’ reactions to a story are based on how closely they identify with a character in it and what he does. The writer can’t do anything about that factor, though. He might produce a perfectly good story that disappoints some readers because their hero doesn’t behave as they envision him behaving.

The various external factors that influence a reader’s reaction to a story are why I’ve never said I like or I dislike a story. Such a reaction doesn’t mean a damn thing.

SRS

translation: Didio sucks

I think it all comes down to the current problem of editors interfering too much. It takes a lot of confidence to trust the writers to do their jobs, but that’s the only way you get good comics.

“How to get INTO editing is something I just don’t know. Whether it requires English degrees or cock-sucking skills, I just can’t say, but I’m inclined to think that it’s a combination of both.”

Yes! I am *so* going to send in my resume!

“An editor should have all the capabilities of a writer, or he won’t be able to recognize and fix problems….”

No. This just a variation on the “you can’t critique X unless you can do it (better) yourself” fallacy. Being able to write can be very helpful for an editor’s job, but it isn’t actually something he should be doing as part of it.

An editor needs to be able to recognize problems (e.g. you didn’t introduce this character, there’s way too much exposition on this page) but he doesn’t need to be able to fix them; that’s the writer’s job to figure out, and the editor should (if at all possible) keep his fingers off the keyboard when that’s done.

The problem is that the editors, like the artists, all come from fan culture. So they have the double problem of wanting to be popular at the con and wanting to see their personal fanfic become official.

Thus Superman loses his outer-undies for being not being kewl! enough, and starts banging Wonder Woman because she’s the only one strong enough to take his super semen.

Most editors want to be writers. This problem comes into play a lot.

The editor shouldn’t want to fix problems himself, but if he can’t, he’s at the mercy of his creators as far as material is concerned, and that would make detecting and fixing problems early on vital.

Take the issue blurb that begins, “Stupendous Man is on a mission to kill ________” or “________ is on a mission to kill Stupendous Man.” The chance of either mission succeeding is approximately zero. If the hero is on the mission, the story probably uses an idiot plot. Decades ago, writers often had an issue’s primary plot subordinate to the continuing subplots, so the reader got something out of the issue. If there are no subplots — toilet tissue. If the writer can’t handle having his story idea rejected, the editor should be able to suggest something else.

Back in June, there was an announcement about NOWHERE MAN. Turned out that Guggenheim apparently had nanotech creations confused with biological viruses. The mistake blew up the premise for the series. I don’t see an easy solution for that problem, but scientific mistakes in story material probably aren’t uncommon. An editor should be able to recognize them and suggest workarounds.

Remember Claremont’s storyline in UXM involving the Foursaken? He became ill, and Tony Bedard tried to finish the storyline, but his material was only tenuously connected to the original one. That was a situation in which the editor should have known what was intended, constructed a plot, and then looked for a scriptwriter. The route they took left readers worse off (IMO) than if the storyline had just been abandoned.

An editor who wants to be a writer is probably in the wrong job. He’s more likely to react to story material as a fan would, and to not possess the required detachment. And if he writes stories with elementary mistakes that an editor would have caught, the mistakes cast doubt on his editing skills and prior work.

If a story is a house, an editor is a skilled carpenter. He can recognize problems and fix them in ways that make the fixes invisible.

SRS

I once had an editor who had never heard of Will Eisner… And another who said I couldn’t just put a rebreather in the mouth of a hero, stating “where are the air tanks?”

Sadly, most editors are lacking creativity which is why they aren’t creators.