If there was ever a reason to go to England, as if more than real mushy peas was needed, this summer’s “Comic Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK” exhibition at the British Library is the one. Not only is it the biggest exhibit of British comics yet, it is by far the most official, and will be, I daresay, the most influential. Curated by Paul Gravett, along with John Harris Dunning, this is no mere “Oh look comics are cool!” exhibit, but a bracing investigation of the often transgressive gutter nature of comics in a specific culture. Since there is little chance I’ll be able to go see it for myself before it closes on August 19th, James Bacon’s photo heavy walk-through will have to do.

Described as a ‘Pivotal Exhibition’ where the British Library wants to have a show ‘that gives creators the respect that’s due to them’, this is indeed a brilliantly conceived and realised exhibition that will be accessible to all while remaining especially satisfying for long-time comic readers. As one walks into what is the largest UK exhibition of comics ever, one realises that this has been a vocational vision to show the thousands who walk in this summer that comics are much more than two-dimensional children’s ephemera.

While British and Irish comics creators have had a massive—perhaps even oversized—influence on the American comics industry, in their native country, comics are, believe it or not, still a little bit outlaw, something Gravett geos into great detail on in this piece on the making of the exhibition:

So you can imagine the thrill of being allowed to explore these astonishing collections and the challenge of picking out which comics to present in Comics Unmasked: Art & Anarchy in the UK, the Library’s first major exhibition on the subject this summer. Usually, the British Library calls mainly on its own expert staff to look after their wide-ranging programme, recently covering propaganda, the Georgians and this autumn, Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination. They had never highlighted comics before, partly because nobody in house felt they had the breadth of knowledge. Two years ago, I joined my colleague John Harris Dunning, journalist, author of the graphic novel Salem Brownstone: All Along The Watchtowers and co-founder with me in 2003 of Comica, the London International Comics Festival, to propose a project and we struck at just the right time. We were both brought in to co-curate what has grown into the biggest exhibition of British comics this country has ever seen.

But again, this wasn’t just Rupert Bear:

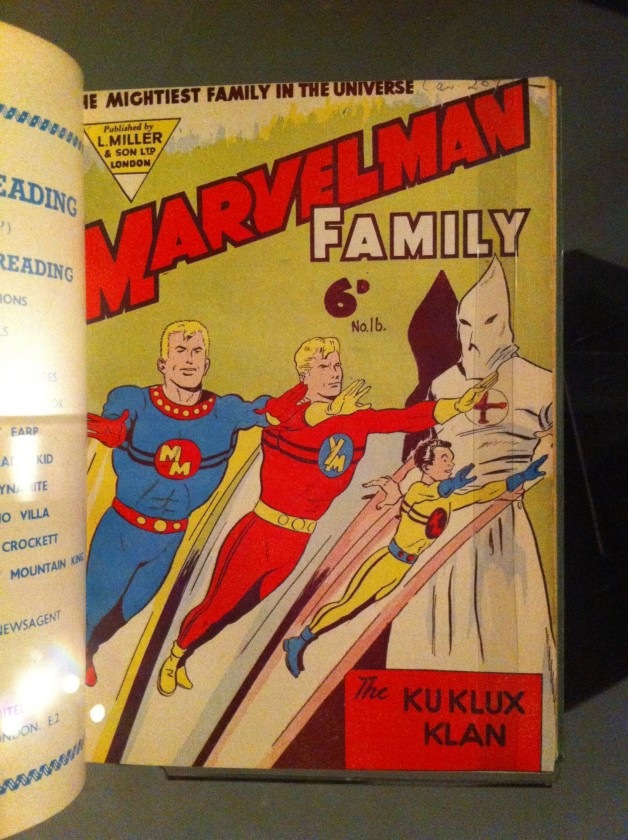

But nor have comics diminished in relevance. If anything they are more a part of culture today than ever before. Comics Unmasked sets out to re-evaluate how mainstream and underground comics have dealt with violence, sexuality, society, politics, heroes and altered states through dreams, drugs or magic. It spans the centuries, tracing back as early as Medieval Bible stories from 1470 (above) and coming bang up-to-date with the boom in cross-pollination with movies, games and more and the ‘infinite canvas’ beyond the printed page offered by digital, interactive and gallery-installation comics. While the exhibition is principally made up of glorious print, we also wanted to demystify the creative process, so there are some revelatory examples of scripts, sketches and stunning original artwork also on loan from Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, Dave Gibbons, Simon Bisley, David Lloyd, Frank Quitely and plenty more, as well as new videos of artists in their studios.

The status of comics in the UK has been on the rise in recent years, with Dotter of Her Fathers Eyes winning a major literary prize, the Costa, being as seminal as Maus winning a Pulitzer 20 years ago. However, it is still an uphill climb, as Gravett expands on in a piece for The Guardian (does this guy EVER sleep?)

These and other arguments about comics have been around for decades. In “The Art of an Unknown Future” in the Times Literary Supplement in 1955, shortly after the government legislation banning horror comics, George Mikes reflected on claims by some pundits that “this new form of expression is capable of creating – indeed, has already created – works of lasting merit”. Mikes mentioned John Steinbeck, who wrote in his introduction to The World of Li’l Abner in 1953 that the strip’s American creator Al Capp “may very possibly be the best writer in the world today”. Mikes was less impressed and, while not wholly condemnatory, was convinced that comics created mental laziness and stupidity. He warned: “if the comics are a new kind of literary form, they may well be a kind of literature to end literature. It is a kind of literature not to be read, only looked at. The comics may flourish and conquer; but their ultimate victory … may mark the end of the reading habit.” That nightmare scenario has not transpired and the reading habit now encompasses both literacy and “graphicacy”. How ironic that many teachers and librarians, once among the most concerted opponents of comics, have more recently become their advocates as a way to motivate reluctant readers and to bring apparently dry, complex texts and subjects to life.

It’s been evident to me that a comics “moment” is definitely happening in England for the last few years, with the rise in indie cartoonists and publishers like Blank Slate, SelfMadeHero and many more. My theory is that with even more “establishment’ coverage of comics in the UK, as crazy as it sounds, comics in the US are going to get EVEN MORE established because if there’s one thing that American media types do it’s ape the Brits. A rising tide lift all renegade artforms.

If you go to see the exhibit please let us know — or comment below.

Comments are closed.