by Todd Alcott

[We’re happy to have screenwriter Todd Alcottback as a columnist with a book length analysis of the Avengers screenplay. Warning: Spoilers! But those those of you who have seen the film, you might just never look at it the same way again.]

The Oscar nominations were announced the other day. To no one’s surprise, the screenplay for The Avengers was not among them. That’s a shame, because the screenplay for The Avengers is a startling model of precision, density and propulsion. It manages to juggle no fewer than ten wildly disparate main characters in its ensemble cast and give each of them weight, clarity and purpose. Dear readers, I’ve worked on many a comic-book movie, none of which ever got near production. To get one superhero narrative to work is damn near impossible; The Avengers soars with seven.

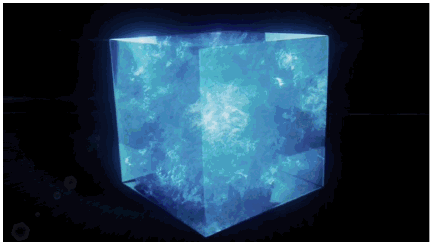

We begin with a blue cube on a black screen. That’s the Tesseract. What is the Tesseract? Well, assuming the viewer has not seen Thor or Captain America, the answer is “Who knows?” But the Tesseract is the very first thing mentioned in The Avengers. It is, of course, the maguffin of the movie, the object around which the narrative revolves. That it has been mentioned in previous movies doesn’t matter. In a lot of ways, and this is an important concept, what the maguffin of any narrative is doesn’t matter. It is “an object of consequence,” and that’s all you need to know.

A deep voice intones: “The Tesseract has awakened.” What does that mean? Again, who knows? What’s important is that there is an object called The Tesseract, and it has awakened, and, based on the seriousness of the voice-over, The Awakening of The Tesseract is a grave event indeed.

Now a guy in a gigantic robe appears on a platform deep in space somewhere. Who and where is this guy? Is he the guy talking? Who, or what, is he talking to? Like the Tesseract, it’s not so important that we “know,” only that we sense the scale and importance of events. The guy in the dark on the weird platform talking to the celestial jukebox in the middle of outer space is talking about Earth in alien terms in a deep, troubled voice to someone or something that is more powerful than he is. What we know now is that The Tesseract, whatever it is, has awakened, on Earth, and that that is a matter of concern to Mr. Bigrobe here, and to his boss on the other end of whatever this device is Mr. Bigrobe is talking into.

Mr. Bigrobe mentions that the Tesseract is on Earth and that he is sending an “ally” to go fetch it from the humans who possess it. We then get a quick shot of Bigrobe handing some sort of glowing sceptre to this ally. So we have a chain of command in just a few short seconds: there is a mysterious “boss” somewhere, to whom Mr. Bigrobe reports, and Mr. Bigrobe, for some reason, can’t go to Earth to get this all-important Tessaract himself, so he is sending an “ally.” The ally, we then learn, is not traveling to Earth alone. No, at some point in his task he’s going to be joined by an army of creepy-looking aliens called The Chitauri. The Ally is going to get the Tesseract, and for this he will be granted the Earth to rule, and the rest of the universe will fall under the control of this mysterious boss.

The movie is less than a minute old, and that’s already a ton of narrative to digest. Too much, probably. Too much, definitely. No one could make any clear sense of what they’ve just been told. So what have we really been told? What we’ve been told, really, is that Big Doings Are Afoot, that forces beyond human comprehension are conspiring against us, and that humanity will, no doubt, be wiped out.

In short, what we now have is “stakes.” Stakes are what give a narrative, or a scene, weight and import and volition. The Avengers is a maelstrom of stakes. An important thing to understand about stakes is that they are directly related to the success of a cinematic narrative. When the stakes are low, the movie feels “small,” and the narrative decreases audience involvement. A movie about a guy who loses his keys is going to be less involving, to most people, than a movie about the end of the world. On a macro scale, less audience involvement generally means less audience. When the stakes are life-or-death, audience involvement increases. So The Avengers takes care to mention, right up front, that nothing less than the fate of all humanity, and the universe, is at stake. Not the planet, not the solar system or even the galaxy, but the universe. Obviously, this movie is playing for keeps.

Who is in the helicopter in the picture above, and where are they going in such a hurry? ”Helicopter,” in a thriller setting, is usually a shorthand for “government.” Only the most powerful people get around by helicopter. This shorthand dates back to the war in Vietnam, where American helicopters rained death on a civilian population for years. The helicopter, cinematically speaking, became a symbol of oppressive authority.

But in this case, “helicopter” means human, as opposed to the creepy alien dudes we’ve seen in the movie so far. So a helicopter, while still a symbol of power and authority, is downright cuddly in the context of this narrative. Whoever is in that helicopter, we know he’s powerful, very powerful, and we also know that he’s human.

Where is the helicopter going? The helicopter is going to some sort of government installation, The Joint Dark Energy Something. What’s happening at the Joint Dark Energy Something is that everybody there is getting the hell out. This, in screenwriting, is called “getting into the scene as late as possible.” We don’t know what everyone is running from, we only know that they are running. This, too, increases audience involvement. The audience leans forward to gather information when they are not spoon-fed it by a helpful narrative. We don’t even get a clear look at the sign. Do we need to know exactly what this place is? Not really — the sheer size of it, which we’ve seen from our helicopter’s POV, is enough to indicate that it is “important,” and the panic erupting all over is enough to indicate that it is in great danger. Again, stakes. ”Important” and “Great Danger.” Concision.

Everyone at the Joint Dark Energy Something is in a panic, except this one guy who’s there to greet the helicopter. This guy is, Marvel fans will know, Agent Coulson, beloved agent of SHIELD. But to the viewer who just wandered in from off the street, all we know is that he is The One Guy Who Isn’t Running Around Panicked. That makes him very powerful in his own right, and the fact that he is waiting for the helicopter makes whoever is in the helicopter that much more powerful. Keep in mind, we’re still only a minute or so into the movie — if nothing else, The Avengers is a sleek deliverer of information. We’ve not only been given a ton of information, we’ve been given it in a highly cinematic style.

And finally, after an exhausting two minutes of movie, we meet our protagonist, Nick Fury, getting out of the helicopter. This is the powerful man in the helicopter, this is the man The Only Man Not Panicking is waiting for. Everyone else is Running Away, this man is Walking Toward. You don’t need to know anything else, he hasn’t opened his mouth, he hasn’t introduced himself, all he’s done is fly in in a helicopter and get out, and already you know he’s very important and very powerful.

(Technically, the true protagonist of The Avengers, is, of course, whoever is on the other end of the celestial jukebox that Mr. Bigrobe is talking to. This turns out, eventually, to be a guy named Thanos, and Mr. Bigrobe turns out to be a guy named, er, “The Other.” The “protagonist” of a story, in the strictest sense, is the guy who set events into motion. Thanos wants the Tesseract, The Other sends Loki [the “ally”] and the Chitauri to get the Tesseract, and it falls to Nick Fury to stop those guys from doing that. This, technically, makes Nick Fury the antagonist of The Avengers. To make this distinction seems picayune, but, in fact, this protagonist problem is why so many superhero movies turn out so badly — it is inherent in the genre that the protagonist of the narrative is the bad guy. The moment you have a main character whose job it is to run around stopping things from happening, you have a reactive protagonist, which means a weaker narrative. When you have a weaker narrative, you end up throwing all kinds of nonsense at the screen, hoping that no one will notice that you have a reactive protagonist. This is, incidentally, why Batman rarely shows up in Christopher Nolan’s Batman movies — Nolan understood that the protagonist of his Batman movies had to be Bruce Wayne, not Batman, and that, for his narratives to succeed, the bad guys had to be reacting to the actions of Bruce Wayne, not Batman reacting to the actions of the bad guys.)

Our protagonist, Nick Fury, gets out of his helicopter, along with his sidekick Agent Maria Hill, and exchanges some rapid-fire dialogue with Agent Coulson as he heads down, down, down into the depths of the installation. He’s arrived in a helicopter, a symbol of power, and now he descends deep, deep underground. What does he talk about with Coulson? ”A bunch of stuff.” The Tesseract, we come to understand, has done something surprising, which has necessitated the evacuation of the installation. The Tesseract, which, again, we don’t know what it is or what it does, is kept deep, deep underground because it’s so freaking powerful.

(Incidentally, why must the installation be evacuated? The answer: because The Avengers, in order to make the ton of money it needs to make to turn a profit, must be rated PG-13. The installation is about to go sky-high, so to speak, and if the movie begins with a catastrophic loss of life, it becomes Saving Private Ryan instead of the colorful spectacle it needs to be.)

Nick Fury gets to the Tesseract Lab and meets up with Dr. Selvig, who seems to be in charge of Things Tesseract. We are told for the third or fourth time in a minute that the Tesseract is doing something weird. This is a useful script note: since so much information is getting thrown at the audience all the time, keep reminding the viewer, in different ways, what the headlines are and why things are important.

What exactly goes on in the Tesseract Lab when the Tesseract is not being weird? I guess Dr. Selvig and company do research on it, and try to figure out how to harness it as an energy source. I say “I guess” because I can’t figure out from the design of the lab what’s supposed to happen there. There’s the Tesseract, held in some kind of Big Round Machine that looks like it was borrowed from Tony Stark’s lab, and then there are a bunch of cables leading to some kind of staging area, and there are scientists who examine the Tesseract by poking at it with a stick. No, really. Obviously, Tesseract Studies are a very new thing, if the level of examination is at the “poking at it with a stick” phase. This, oddly enough, turns out to be important later.

Dr. Selvig grunts some lines about the nature of the Tesseract. It’s from outer space, it’s being weird, no one knows what to do, outside of poking at it with a stick.

Nick Fury has barely spoken to Dr. Selvig about the possible imminent destruction of the planet before he asks about another character, Agent Barton, or Hawkeye. The Avengers is supremely busy, with five important characters, all of whom will have competing and intertwining agendas, all being introduced in the first four minutes. Nick Fury chats with Barton, who informs him that the Tesseract is “a doorway to the other end of space.” Why does Barton tell Fury this, and not Dr. Selvig? For that matter, why does Fury need to talk to Barton? For that matter, why is Barton even there?

Fury talks to Barton so that we will understand that Hawkeye is a proficient, if detached, agent of SHIELD, so that when SOMETHING BAD happens to him in a moment, we will have a vague understanding of who he is and what has been damaged.

Right on time, that something bad happens. The Tesseract goes kerblooey and blasts out a beam of energy at the staging area at the other end of the lab (still not sure what that’s doing there) and, in a flourish of smoke and in a pose suggesting Hannibal Lecter, our chief antagonist appears, Loki. This is, of course, the “ally” The Other spoke of, and here he is, with his special alien sceptre. I was about to identify Loki as our primary antagonist, but The Avengers does an unusual thing with its antagonists; it staggers them throughout the narrative, tag-teams them almost, so that their seven-hero narrative has plenty to do.

(We are led to understand that the Tesseract has opened from The Other’s end of space. Are we told how The Other manages to do that, exactly? And if he could have done it at any time, is there some reason why he’s only doing it now? ”The Tesseract has awakened,” do they mention at some point how or why that happened? Did I miss something?)

In short order, we learn that Loki’s spear can shoot energy bolts, suck human souls out of their bodies, and also be used as a club or spear. Loki trashes the Tesseract Lab (not that it was a model of regimented order to begin with) and tussles with Barton, sucking out his soul and, apparently, turning him to his side.

Nick Fury swipes the Tesseract (apparently no one thought to put it in a box or anything, because otherwise how would you poke at it with a stick?) while Loki steals Dr. Selvig’s soul and monologues about his intent: he is here to enslave humanity. Barton, now evil, shoots Fury. Loki takes back the Tesseract and he, Barton and Selvig hot-foot it out of there.

Turning Barton evil in the first sequence of the movie is The Avengers‘ first stroke of genius. In a narrative with seven superheroes, get one out of the way as soon as possible, but in a dramatically important way. Now you only have six superheroes to deal with, and a built-in payoff in Act III.

Nick Fury responds to being shot the way anyone would — he yanks the bullet out of his chest like it’s a piece of gum stuck to his shirt and gets on with things. The beauty of The Avengers is in the way it perfectly captures the comic-book experience: it is both very serious and very silly at the same time, often in the same breath. Its entire cast understands this about the script: it must be played with utter sincerity, especially when it’s at its most ridiculous.

Big chase scene, as Loki and his team try to get out of the installation before it collapses. (Why is it collapsing? No particular reason is given. The blue energy whatsit of the Tesseract causes a collapse of some kind, somehow, for some reason. It’s from outer space, it doesn’t need physics.) Barton and Maria Hill get great action moments, and we begin to understand another of the great narrative ideas of the movie: it’s fun to see superheroes fight supervillains, but it’s even more fun to see superheroes fight each other.

The installation collapses, mostly bloodlessly, and Loki escapes with the Tesseract. (It seems kind of odd that a Norse God has to escape in an SUV, but I guess SUVs never entered Norse mythology.) Our protagonist is at war with a Norse God working for an alien force, which causes him to turn desperate: he needs every weapon in his arsenal.

Now that our narrative has a protagonist, the question, as always, is “What does the protagonist want?” Superficially, Nick Fury wants “to save the world,” that most generic of motives. To save the world, Fury must get a group of superheroes from vastly different backgrounds to work together.

Surprise! What the protagonist wants is exactly the same thing as what the writer-director wants! If Joss Whedon cannot succeed in getting his dog’s-breakfast of a cast to mesh, meld and work as a unit, his narrative will fail and no one will go see his movie. This not only gives the writer a keen insight into his protagonist’s character, it’s a stroke of genius, giving the narrative a spine that would otherwise make it an ensemble comedy-spectacle, an It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World with superheroes.

We now move briefly to Russia, where we meet Natasha Romanoff, aka Black Widow. This is the first of a number of “assembling the team” scenes, which will form the basis of Act I. ”Assembling the team” acts can be a real drag, a laundry list of scenes that don’t further the action, especially when the audience knows that the team will assemble. ”Avengers Assemble!” is the freaking catchphrase of the whole franchise, how could they not assemble? The screenplay gets around this potential narrative cul-de-sac in a number of ways, starting with the excellence of the individual scenes.

Natasha is Somewhere in Russia, in a black evening dress, being interrogated by Some Bad Guys. Who is Natasha? I don’t really know, I’m only a little familiar with her, but her introduction in The Avengers certainly gets my attention. It’s a brilliant scene, one that tells you everything you need to know about the character and delivers that information in a concise, funny, inventive and dramatically effective way.

We meet her tied to a chair, teetering on the edge of a big hole in the floor. Our hearts instantly go out to her: that poor woman! She’s being interrogated by some really scary dudes about something or other, it really doesn’t matter, it makes no difference, the point is that she is in a position of extreme duress and discomfort and facing impossible odds for escape.

Except, of course, that she is not. One of the thugs gets a phone call from Agent Coulson, who has (or says he has) a bomber ready to kill them all. (This elevates Coulson quite a bit in the narrative, from “Guy Subservient To Nick Fury” to “Guy Impressive In His Own Right.”) And we learn that Natasha’s helplessness is an act, that she has been using her helplessness to get the Bad Guys to reveal more information than they would have otherwise, and that she is perfectly capable of taking care of herself, reversing her situation and making the Russians the helpless ones, in a hugely impressive fight scene.

She’s reluctant at first — she tells Coulson “I’m working.” So we see how she responds to a guy capable of destroying a city block with a phone call — “Can this wait?” Coulson tells her “Agent Barton has been compromised,” and that’s sets her into action. So we see that Black Widow is not motivated by “duty to her superiors” but rather by personal friendship: Barton means something to her. This makes all the difference in the world.

A few years back, I did a piece about the difference between Bruce Timm’s Justice League series and the Superfriends show of the 1970s. I found that the difference between the two shows is that Superfriends treats the Justice League as all the same protagonist, while Justice League emphasizes the differences between all the characters and mines dramatic gold from those differences. The same applies here: a simple line like “Agent Barton has been compromised” changes The Avengers from a movie about a fait accompli triumph of team spirit to a movie about people, and superheroes need to be people, no matter how broadly drawn, if we’re going to care about them.

(I love the shot of Coulson waiting on the phone while Natasha turns the tables on her captors. Listening to Black Widow beat up thugs is Coulson’s version of hold music.)

We now scoot over to India, where we meet Bruce Banner. Or rather, first we meet a little Indian girl, who dashes through a slum in search of Dr. Banner to aid her dying father. The little girl’s desperation is palpable, and the good doctor can hardly help but follow her. Our hearts go out to the little girl, and we desperately want to see Dr. Banner help her father. Like everything in The Avengers, this is played out very quickly but with great efficiency. An affecting little drama is created, as our protagonist shifts from Nick Fury to Black Widow to this little girl on her mission to save her father. And, because the direction is so sure and the production design so convincing, we accept the truth and stakes of the girl’s plight.

The little girl, it turns out, is bait, set by Natasha to capture Bruce. The little girl, in her helplessness, plays on Bruce’s good nature and feelings of sympathy and gets him to go to an empty house. There’s a wonderful moment just before they get to the house where the police roll by and Bruce shields the little girl with his body, as though keeping her out of the hands of the authorities. He is, of course, keeping himself out of the hands of the authorities, but he plays the moment for the sake of the girl, as “the caring father.”

Kurt Vonnegut once said “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be very careful what we pretend to be.” This applies to no one in the comics universe more than Bruce Banner, who must be very careful indeed what he pretends to be. His life as a doctor is, in its way, a performance, or an act of contrition, a way to pay for the things he does as “the other guy.”

When the little girl leaves Bruce like a groom at the altar, we realize: the little girl isn’t just like Natasha, she is Natasha, using the patented Black Widow technique of getting men to let their guard down by putting on a weak-and-helpless act.

What does Natasha want? Natasha, in this scene anyway, wants to get Bruce to help look for the Tesseract. A murmuring of “gamma radiation” suffices as a reason why it absolutely must be a radically unstable monster who is brought in to help look for the Tesseract.

The shift from Fury to Natasha (actually from Fury to Coulson to Natasha) keeps the narrative jumping. If it were any one person going from door to door looking for heroes, the laundry-list problem might again assert itself. (See the opening of Ocean’s 12 for an example of this – Steven Soderbergh, surely one of our greatest living directors, must come with with a dozen different dazzling ways to shoot and cut the same scene, just to keep us entertained through his “gathering the team” sequence.)

The action of the scene is simple: Natasha wants Bruce to come with her and Bruce doesn’t want to go. Yet the scene is comparatively leisurely, and, since we already know that Natasha is a master manipulator of men’s desires, her skill in the negotiations isn’t new. What is left is character work, a “getting to know Bruce Banner” scene. The performances are warm, detailed and canny, and it’s almost a love scene, where the lovers dance around not the subject of attraction but the subject of Bruce’s gigantic green alter ego. They dance around it so much that Bruce finally threatens to let it out, just as a tease, just “to see what you’d do.” What Natasha would do is instantly pull a gun, the love scene over, the dance done. The Avengers is, in many ways, a cautious love story with multiple partners, the question being, can our love outlive our conflicts, can it outlive our flaws?

Now we check back in with Nick Fury, who, it turns out, is answerable to some sort of council. This Council, like all councils, wants to rein in the wild-card Fury, to control him, much like Bruce Banner needs to control his own fury. I mentioned before that Nick Fury’s goal is the same as the writer-director’s. If that’s true, then this Council is the movie studio. The world is at stake and the council, like the movie studio, wants to go with the safe bet, a “Phase Two” program we’ve heard mentioned in passing. But Fury wants, instead, to take this crisis as an opportunity to build a family, to not just assemble a team of soldiers but to become their father, exactly in the way a director becomes a father to his crew. And, as on a film shoot, romances bloom, friendships are struck, fights are had, and eventually the job gets done.

When Fury talks about assembling the Avengers he talks about them like they’re a group of unruly foster kids he wants to build into a little-league team. He cares about them, even as he knows he may be sending them to their deaths. It’s like he’s using Loki’s threat as an excuse to spend time with his estranged children.

Nick Fury goes to find Steve Rogers, who’s recently been woken from a seventy-year coma. Sending Fury to Steve instead of Natasha makes the scene fresh, not another item on a to-do list. What does Steve want? Steve is a patriot literally frozen in his time, a time when the US was the beacon of the world. And so The Avengers takes on a political dimension, as the frozen soldier confronts a present where the US is decidedly not the beacon of the world. The present takes the form of Fury, who, with his leather trenchcoat and eyepatch, looks more like the Gestapo Steve fought in WWII than an American soldier. He can’t trust Fury, partly because of his darkness and cynicism, and partly because Fury represents ideas so strange they would be hard for anyone to understand, ideas like alien artifacts, parallel dimensions and gods among men.

Fury lives with this stuff, and it wears on him — no one should have to deal with the brand of bizarre he sees every day. Steve, of course, knows about the Tesseract, because the Tesseract was the Maguffin of his movie too, much better plot placement than a half-hearted mention of gamma radiation. The screenplay slowly, slowly teases out information on the Tessaract in order to avoid what we screenwriters call an “information dump.” The exposition is parceled out a line or two at a time, keeping the emphasis on character interaction — it’s not “What happens if Loki has the Tessaract?” but “How will Steve Rogers ever trust Nick Fury?” The former is already settled, we know The Avengers will succeed, we’re paying money to watch them succeed, but the latter, “Will everyone learn to get along?” is where the real meat of the movie lies.

Perhaps the most impressive feature of The Avengers is the way it balances the separate stories of its wildly disparate leads, so that we never, ever feel like “Oh, another Thor scene, ho hum, I guess it will end soon.” The screenplay keeps so many balls in the air that everything feels lively and inventive and fun, even when the plot isn’t being forwarded, or especially when the plot isn’t being forwarded. The balance of the superheroes is so strong, here it is, twenty-three minutes into the movie and we are suddenly thinking “Oh yeah, Iron Man is in this movie too, I totally forgot.”

What does Tony Stark want? Tony Stark wants to show the world that the machine that powers his heart, and his suit — his life, really — the Arc Reactor, is also a viable energy source. “Energy,” in this instance, is just another word for “power,” and power is what superhero narratives are all about — who has it, who does not, who wants it and what they will do to get it. In the case of Iron Man, “power” defines the two sides of Tony’s life — he is both a weapons merchant, a power broker of the purest kind, and a power provider, with his Arc Reactor. He bets both sides of the coin, even if he stops selling weapons, he is still a weapon himself, a walking, thinking weapon.

Of defense, of course, which is always a problem of a superhero narrative — if the protagonist has more power than those around him, he must, must use that power in defense of those people. The trick is how to make that character interesting, to not make him a Boy Scout. Batman makes its protagonist obsessive and brooding, Hulk makes its protagonist an agonist who doesn’t want to use his powers at all, and Superman — well, that’s part of the reason why Superman is so hard to put in a cinematic narrative, he’s both a boy scout and resolutely unbeatable. Iron Man, on the other hand, makes its protagonist kind of a jerk — flawed, vain, conceited. If Tony Stark’s goal is to show the world that the Arc Reactor is the key to the future, what he’s really saying is “Love me, I’m not such a jerk after all.”

Who has power in The Avengers isn’t as interesting as who wants it, and who loves it. Thanos, apparently, has all the power in the universe, except for that one thing. The Other, it would seem, has as much power as any being could hope for — he towers over Loki, a freaking god, and has armies at his disposal, but is a mere lackey in the presence of Thanos, and a bootlicker at that. Contrast him with Nick Fury, who also must report to a mysterious disembodied power, his Council, but who holds them at arm’s length, with distrust, and wants primarily to create a family. Then contrast Fury with Coulson, who is polite and diffident with Fury but holds a stunning amount of his own power, then contrast Coulson with Tony Stark, who treats Coulson like a teaching assistant he has to be nice to.

Coulson, “Phil” to Tony’s girlfriend Pepper Potts, busts in on Tony and Pepper while they’re in the middle of a celebratory glass of champagne: Tony has made his first steps away from “bad” power and toward “good” power. Luckily for us, this hasn’t actually made him less of a jerk.

(That “Phil,” inserted as a tiny, tiny joke, intended to give the merest suggestion of a past between Pepper and Coulson, will have repercussions later, another example of how the smallest moments in The Avengers, delivered in the most casual ways, pay off.)

Coulson gives Tony a huge file to study and Pepper takes her leave, with a whispered promise of later sex. Coulson, stuck holding Pepper’s champagne flute, averts his eyes and looks uncomfortable. It’s an answer shot to him waiting on the phone while Natasha beat up her Bad Guys — Coulson, while jetting about saving the world, waits for super-spies to beat people up and then waits for billionaire industrialists to get sex talk from their girlfriends. It says the most about Coulson in the fastest way possible, again, humanizes him, in ways that will pay off later in the movie.

Who is Coulson, anyway, in the context of this drama? He wields enormous power, he clearly outranks the individual heroes involved, and yet he doesn’t merely defer to them, he loves them, they mean the world to him. Coulson, in short, is the audience. If Fury is the writer/director, Coulson is the audience. But not just any member of the audience, the core audience. He is the way comics readers imagine themselves on an adventure with one of their heroes: the coolest sidekick ever. He’s blase, unassuming, patient, unflappable and openly adoring, as we see in a moment, when he gushes at Steve Rogers as they head out to the SHIELD carrier.

And here, at the thirty minute mark, we end Act I of The Avengers. The threat has been established, the team has been built (almost), the characters established. They’re in it now, whatever “it” is.

I spent an amount of time trying to discern the act structure of The Avengers, assuming that a movie as long as it is must have at least four acts if not five. Despite its length and complexity, it appears The Avengers has only three acts. The first act is 30 minutes, the last act similarly, the middle act well over an hour. My reasoning for that to come.

At the top of Act II of The Avengers we begin where we began Act I, in space, with The Other checking in on Loki. They talk about the Chitauri, to remind us that that’s a thing, they talk about the mysterious boss at the other end of the jukebox, and remind us that the boss wants the Tesseract, Or Else. We also learn that Loki was once “the rightful king of Asgard,” which gives him the horse in this race. Loki may not be the Ultimate Boss of The Avengers, but he has a much more compelling motivation: revenge against his brother Thor, who exiled him. This narrative stroke, to make two characters from Thor the hinge of the screenplay, is masterful: the traditional studio approach would be to take the wild cards of the franchise (Norse gods!) and ignore them completely, or give them only token attention. But to put Loki and Thor at the middle of this gigantic tentpole money-making machine provides a useful bridge between the mundane (Barton), the fantastic-but-still-believable (Iron Man), the straight-out fantastic (Capt America, Hulk), and the gonzo sci-fi alien spectacle of the Chitauri. The mere fact that one movie embraces all these characters is daring enough, but the screenplay for The Avengers distributes its narrative effects so judiciously and balances its characters so well that a common, non-comics-reading audient sees a Norse god taking orders from an alien in a robe and thinks “Okay, sure, I get it.” The fact that Loki’s motivation is both human and not centered on “conquering the universe” but one-upping his good-looking brother gives the narrative an appreciable scale and, thus, creates audience involvement in something patently absurd.

Now that we’ve checked in with Loki and The Other, now we check in with SHIELD and its array of impressive transportation vehicles. Act I gave us Nick Fury arriving in a helicopter at a secret government installation, Act II gives us Coulson and Steve Rogers arriving in a fancy heli-jet on an aircraft carrier. It might sound trivial, but again, the relative power of the characters is telegraphed by their mode of transportation, and Nick Fury will have the last laugh in this regard.

Natasha meets Capt America. She’s blase but tips Coulson’s hand as a super-fan, underscoring Coulson’s humanity (and position as audience surrogate — if Coulson has a set of vintage Capt America trading cards, maybe Capt America is cool after all!). Capt America meets Bruce Banner, and both characters seek to put the other at ease: Capt America brushes away concerns about Bruce’s alter ego, and Bruce tries to relate to Capt America’s naivety. Both characters, then, are shown to be naive as the aircraft carrier sprouts rotors and lifts off into the air. This, surely, is the largest, most intimidating vehicle possible on Earth (and yet, the fact that it’s a recognizable fuel-burning machine and not an alien-artifact-powered flying saucer makes it impressive, yet understandable).

Steve and Bruce head to the bridge, where we see just how large and impressive Nick Fury’s operation is, and it’s telling that the immortal super-soldier and the green giant look awed and a little lost when faced with a well-staffed technological marvel. Technology, even of the old-fashioned kind, is still a force to be reckoned with.

Now we check in with Barton and Dr. Selvig, in thrall to Loki, toiling away at the Tesseract. Dr. Selvig, for some reason, needs some iridium to do whatever he needs to do with the Tesseract. He’s become a shiny-eyed zealot, he loves Loki for bringing him the power of the Tesseract. He’s the Edward Teller of the piece, the scientist in search of “truth” and in love with power. For him, the Tesseract is an end in itself, not a doorway or an energy source. Thanos wants the power to conquer the universe, Tony want the power to light the world, but Dr. Selvig just wants to be in the presence of power itself.

Back at the heli-carrier, Coulson, we find, is pestering Steve Rogers for an autograph for his vintage Capt America trading cards. Coulson, a man who wields enormous power in his own right, is, on another level, nothing but a fan. He mentions that it took him years to aquire his “complete near-mint” set of trading cards: apparently the monstrous level of technology available to agents of SHIELD does not allow him to get everything he wants. For some things, you just have to go on a pilgrimage.

Meanwhile, in Stuttgart, Loki drops in on a fancy museum party of some sort, to get an eye-ball print off a guy so that, across town, Barton can use that print to break into a lab and swipe some iridium. Why does Loki need to participate in a heist? Is there no one else on his staff qualified to walk into a lobby, grab a guy and stick a thing in his eye?

Why a museum? Why, for that matter, Stuttgart? The museum setting represents “culture,” and the European setting makes it “old culture.” Loki, no stranger to old European culture, relishes this chance to shock the squares at the museum, to flex his muscles, to try out his desired role of overlord. He demands that the bluenoses kneel before him. The target audience of The Avengers doesn’t identify with the bluenoses, so the point is not to give us a taste of Loki’s wrath. Rather, it is, like so many of scenes in the movie, a character beat, showing Loki for the kind of petulant leader he would be — vain, short-fused and childish.

Loki demands that the crowd kneel, but an elderly man stands up and challenges him, and then we understand why Stuttgart. The elderly man who stands up to Loki is meant to remind us of an earlier German generation, the one that didn’t stand up to Hitler. Invoking Godwin’s Law at this juncture paves the way for Capt America to show up, getting to finally fulfill his fantasy of punching Hitler. Iron Man, playing 21st-century cynic to Cap’s 20th-century idealist, shows up to help, and the two of them capture Loki, surprisingly easily. It’s unexpected, anticlimactic even, to see Loki go so easily, but of course he has other tricks up his sleeve.

Steve Rogers and Tony Stark now share a moment on the transport back to the helicarrier. The scene highlights the difference between Steve and Tony — Steve, still an idealist, suspects something is wrong but can’t imagine that the something wrong could be on his end, while Tony, cynical billionaire, questions everything, every angle, including Nick Fury’s, especially Nick Fury’s.

Enter Thor, who nabs Loki and absconds with him. ”Now there’s that guy,” sighs Tony: not even a Norse god, well, a second Norse god, can faze him.

Steve, on the other hand, isn’t impressed with Thor himself, but for different reasons. ”There’s only one God,” he says, “And I’m pretty sure he doesn’t dress like that.” Thor might as well be Red Skull as far as Steve is concerned: unusual, maybe, but no cause for alarm.

Why, the reasonable viewer may ask, does Thor even have to be in this movie? Surely there are enough characters to serve a narrative here. The answer, I’m sure, has to do with commerce instead of art, but the screenplay plays him beautifully — his conflict with Loki is — forgive the expression — human, in a way that superhero conflicts rarely get a chance to be. The idea of an unseen alien overlord wishing to conquer the universe is abstract in the extreme, but the idea of two super-powered brothers duking it out over bad blood is visceral, and, in its own way, warm. By making Loki the chief antagonist, the movie hands the best motivation to Thor, the character who, let’s face it, is the least cool of a very cool bunch. Tony Stark wants his energy source, Steve Rogers wants to fell a potential dictator, but Thor wants to settle some hash with his brother.

Thor’s scene with Loki brings up a valid question about leadership, and about superheroics for that matter. Thor is a caring but absent god, dropping in to save this or that town or maiden, but Loki wants order, as dictators do, with himself at the seat of power. Which raises the eternal question, if Superman is capable of dispensing truth and justice, why doesn’t he? Why doesn’t he fly around the world, ousting dictators, feeding the hungry, melting the guns, dismantling the bombs, eating the plutonium, re-educating the terrorists, irrigating the Sahara? Does he not care? Between him and The Flash, they could probably make the world a paradise in an afternoon. Why doesn’t that happen?

The real answer, of course, is “But then there would be no more stories to tell,” and the comics publishers would go out of business. The more common answer is “But if a superhero solves all our problems, we no longer have free will,” which is the same argument for why God allows evil in the world. The impulse to create superheroes in the first place was a 20th-century leap of faith, new gods for a new age, an age of clear good guys and bad guys and fearsome technological advances. The Avengers makes no bones about how America has betrayed its ideals as a pillar of truth and justice, and in its shiny, pop-culture way it asks how one is heroic, what defines heroism, in this complicated time where every hero casts a shadow.

The answer for Thor, of course, which points back to Steve Roger’s comment, is that he’s not really a god, he’s a Norse god, which is a very different thing from the Christian God. Norse gods, and their pre-Christian friends from Greece, were always a very human bunch, powerful but prone to jealousies, pettiness and rages. And, in some ways, destructible. It makes sense that Thor doesn’t do much to help the world he’s sworn to protect, he comes from a different tradition, a tradition where the gods had their fights and problems and the people just kind of had to deal with them.

Tony comes along to get Loki back from Thor, and a fight ensues, this time between god and technology. Steve Rogers may be a man out of time, but Thor is a god out of time and doesn’t have to bear Tony’s arrogance and cynicism. They fight, and Steve joins in, and Loki sits and watches instead of running away, the brawl is too entertaining to miss.

The Thor/Tony/Steve fight is a rare instance of hugger-mugger in The Avengers. ”Hugger-Mugger” is what I call a bit of business that is entertaining and even spectacular, but then ends and everyone goes back to doing what they were doing before. The stakes of The Avengers don’t rise appreciably in the midst of the fight: all we really need from the sequence is for Thor to come aboard the journey. The fight brings him in in style and sets him at odds with the mere mortals who challenge him, but Loki still winds up exactly where he was before, in the clutches of SHIELD.

So now Loki is aboard SHIELD’s helicarrier. The viewer is a little confused: one street fight in Stuttgart, and the bad guy is captured? Loki’s introductory shot, so reminiscent of Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs, is not a coincidence. Loki will go on to make the Lecter comparison concrete. Not only will he play the Lecter suit of corrupting minds from his cell, he is, like Lecter in Silence, not the real anatgonist, only the most charismatic one, the one most fun to watch.

Elsewhere on the helicarrier, Bruce Banner works at a high-tech machine of some kind, doing science stuff, as Loki is paraded by in cuffs. (How you cuff a Norse God, I’m still not clear on.) Loki gives Bruce a sly smile as he passes. He is a god of chaos, an expert in loss of control, the thing Bruce fears the most. Moreover, he is on his way to the helicarrier’s big-deal high-tech unbreakable prison cell, a cell designed to hold Bruce, should he ever hulk out.

Fury, playing Dr. Chilton to Loki’s Lecter, explains how the cage works: if Loki misbehaves, he gets dropped 30,000 feet to the ground. I’m not sure how that’s supposed to affect a Norse god, but I’ll take it on faith that it’s bad for him. Loki, undaunted, lectures Fury on the nature of the movie’s maguffin: the Tesseract is “Power” in its most plastic sense: it can light the world, or put it in the thrall of an oppressor.

Next, we have a powow scene between Bruce, Steve Rogers, Thor and Natasha Romanoff, discussing what to do next and catching the audience up. Ordinarily I chafe at these kinds of expository scenes, and there are many of them in The Avengers, but this is the culmination of several scenes, played out piecemeal in Act I, the information finally strung together for the first time. The Avengers understands that it’s throwing a lot of sensation at its audience, a lot of characters, a lot of imagery and dialogue and conflicts and weirdness, so it’s been very careful to parcel out its exposition, so that the key components of the plot, “Tesseract,” “Loki,” “Chitauri,” “Portal,” “Army not of this world,” have been mentioned but not explicated until now. That strategy keeps this scene from being an info dump, and invites the viewer in, makes the audience one of the team.

Tony Stark and Coulson enter the meeting. Tony is caught in mid-sentence, murmuring something to Coulson about “flying him into Portland” to “keep love alive.” Again, off the cuff, personal, not related to the plot, barely heard, but a tiny little narrative time bomb to detonate later.

Tony catches the team up on iridium, which Dr. Selvig needs for the portal Loki is building to let the Chitauri through into our world. Tony shows off, playing the jerk to cover for his planting of a device on Fury’s bridge. Tony, like Robert Downey Jr.’s other big-ticket role Sherlock Holmes, uses his intelligence, callousness and cynicism to hold the world at arm’s length: if people dislike him they won’t want to be around him, and he’ll get to do his work. Which, the screenplay reminds us, he’s very good at: Iron Man is not merely a suit, but a genius asshole in a suit.

Tony and fellow nerd Bruce head to the lab for some science. As you can see from the above still, “science,” here, involves pointing a price-scanner at a shiny stick and reciting a bunch of sciencey-sounding stuff. What is happening, dramatically, is that Tony and Bruce are bonding, the man who lives to keep tight control of himself and the man who lives to express his every whim.

Steve shows up, and he and Tony expand on their earlier conversation contrasting “good soldier” with “cynical bastard.” When pressed for an opinion on SHIELD, Bruce tries to retreat to a place of pure science (which connects him with Dr. Selvig, who loves the Tesseract for itself and not for its applications). He connects Fury’s desire for unlimited energy (or “power”) to Tony’s Stark Tower, which runs on an Arc Reactor, ie the same thing that runs his heart. The Tesseract, and Loki, and Fury, are thus elegantly tied to Tony and made his antagonists, which makes Tony an antagonist to our protagonsit Fury — Fury’s not going to have an easy time getting his super-family to work together if one of them suspects the father-figure of being dishonest.

Tony and Bruce then discuss their parallel super-powers. Tony’s engineering brilliance caused him to create the Arc Reactor, which not only saved his life but gave him his life’s work. Bruce, on the other hand, was given his powers through an accident and sees them as a curse, a terror to be avoided. We’ve seen the problems of Dr. Banner dramatised for decades now, but somehow the TV shows and movies never managed to get him this level of denial. Dread, yes, but not denial. Bruce in The Avengers isn’t just hoping that The Hulk doesn’t appear, he’s made it his business to pretend “the other guy” doesn’t exist. Tony, ever the hedonist, pushes Bruce to indulge his lust for power, which also ties him into the movie’s theme of power and its uses — in this case, power as a tool of self-actualization. Why be a brilliant scientist if you can also be a giant rage monster?

We briefly check in with Dr. Selvig, who is in a mobile laboratory, adding his stolen irridium to the Tesseract for whatever purpose. ”Checking in with the Tesseract” generally signals an act break in The Avengers, but, as I indicated before, this time it does not. We screenwriters define an act break as the irreversible course change in the protagonist’s path, so if Nick Fury is the protagonist of the piece, his path does not alter here, he does not change direction. Lots is going on in the narrative, but Fury is still on the path of “getting his charges to work together to find the Tesseract.”

Next we have a brief scene where Coulson lets Thor know that Jane Foster, Thor’s significant other, has been moved out of harm’s way. This piece of exposition, meant solely to mop up a continuity issue between Thor and The Avengers, is given to Coulson in order to further humanize him. If Fury is the father of the piece, Coulson is the mother. Fury fulminates and plans while Coulson cares.

Thor, for his part, wonders if superheroics are really so useful in the human world. It’s nice to be a god, he reasons, but gods are human too, and when they fight, as his kin — and certainly the Avengers — do, the destruction visited on the human world is terrible. Better, perhaps, to be an absent god, to be rumored and feared, but essentially unknown?

Fury knows what he wants from Thor: to have a god torture a god until that god gives up his secrets. Does that constitute a turning point for Fury? Fury had mentioned to Steve that “America has made some mistakes” since WWII, is the torturing of prisoners one of those mistakes? If so, is torturing Loki not a thing that Fury was thinking of doing until Thor came along? Is that Fury’s turning point, the “whatever it takes to keep the world safe” excuse that’s been used by the US since 9/11 to justify committing war crimes? The Avengers, in a way, is about Nick Fury’s desperation. How desperate is he? He alluded to being plenty desperate earlier — was he prepared to torture prisoners then too?

The narrative then puts a pin in Fury’s desperation, as, in a surprise twist, Fury does not send Thor to torture Loki, but instead sends Natasha, in the best scene in the movie, and one of the best scenes of any movie in 2012. Deliberately lifted from Silence of the Lambs, this scene shows how you do that, how you take a classic scene, pay homage to it, then lift it out of its context, flip it around, make it pop, get a laugh and advance your plot. And it all comes from character.

Natasha goes to Loki, we think on her own, we think behind Fury’s back, to plead for Barton’s life, to plead for some measure of humanity from Loki, in the same way that Clarice Starling goes to Lecter in his cell in the Tennessee courthouse in Silence to plead for the identity of Buffalo Bill, to save the life of a kidnapped young woman. Loki, like Lecter, is addicted to cruelty, and uses Natasha’s vulnerability as a lever against her. Natasha, like Clarice, confesses her darkest secrets and desires, in the hopes of warming Loki’s heart. But Loki, unlike Lecter, doesn’t care about his interlocuter, doesn’t have Lecter’s curiosity about the human heart. No, he’s got all of Natasha’s secrets already and he uses his knowledge to make her feel worse and worse, crowing in his triumph at her agony until he spills his own secret — that he allowed himself to be captured in order to have access to Bruce Banner. And, because we’ve seen Natash do this before, it is both completely surprising and completely expected that her agony is all an act, that it is she who’s been playing Loki the whole time. Loki is a very poor player, focused solely on his own sense of power, in love with his own voice, never thinking of what might be coming up to blindside him. He’s been rehearsing his triumphal speeches for eons and keeps getting frustrated when the crowd blows raspberries at them.

This means that Nick Fury’s path does not change in mid-movie, that, for all his desperation, torturing a prisoner was not something he was willing to do (either that, or Natasha took the alternate route upon herself while Fury was busy elsewhere. Fury, however, now must deal with Stark and his suspicions, which bring with them a whole other set of problems.

At this point The Avengers‘s temporarily becomes Watchmen. That is, it becomes a superhero narrative about the nature of a superhero narrative. It’s been many things up to this point, but now it folds in on itself and comments on itself. Suddenly, Tony Stark, Bruce Banner and Steve Rogers all discover that Nick Fury wants the Tesseract not to light the world but to build weapons of mass destruction. Fury, in his defense, says that, until Thor came along, SHIELD didn’t need weapons powered by the Tesseract. His argument is that we need super-weapons to fight against superpowers. Does this eliminate metaphor from The Avengers‘s screenplay? That is, can a screenplay about superheroes keep going if one draws attention to the fact that the superheroes are, in fact, superheroes?

This is, of course, another key problem of every superhero movie: with no metaphor, the superhero drama quickly becomes silly. Superman as an idea is tremendously powerful and appealing, but if you spend too much time dwelling on the physical aspects of what exactly Superman is and how he might affect the world, that is, if you ask what if Superman were real, the story becomes about something other than the idea. This is one of the reasons why Batman has soared in the 21st century as a movie franchise while Superman has had trouble gaining traction: the Christopher Nolan Batman movies have largely taken the fantasy out of a fantastic piece of material and allowed Batman to operate without a metaphor. Batman can do that because it’s endemic to the character: he’s a real guy. That’s one of the reasons why it’s okay that Spider-Man fights characters as ridiculous as The Lizard: in order to justify an outlandish hero, you must give him an equally outlandish villain. (In my analysis of Batman and Robin I mention how the decision to make Mr. Freeze the antagonist of the movie was the decision that led the movie down its narrative rabbit hole: the entire movie had to be made ridiculous in order to justify its choice of bad guy.)

The Avengers, and the preceding Marvel movies, have done a great job of “grounding” their characters. Most importantly, they have put character first, superpowers second. It’s not that Tony Stark has a cool suit, it’s that Tony Stark has a cool suit. The Iron Man movies have made it explicit: the tool is not the man, and different men in the same suit accomplish very different things. Bruce Banner dreads the Hulk, but Tony Stark thinks Bruce should let his freak flag fly: they’re different guys given similar powers, and they respond in different ways. That seems pretty obvious, but it is, in essence, the key to the Marvel approach. The typical superhero story begins “What if a guy got superpowers?” But Marvel has always started with “What if this particular guy got superpowers?”

But back to the earlier question. If a movie raises the stakes on its own metaphor, is that metaphor still a metaphor, or does it become literal? The Avengers knows it’s taking a big risk in doing so, and check out what the director does. In the midst of the big scene where all the characters yell at each other about how screwed up everything is, the director literally turns the camera upside-down to show how we’ve gone through the looking-glass, so to speak. Fury tells us that SHIELD wants super-weapons to deal with supervillains, and everyone’s reaction is to shout him down, when, in fact, they’re all part of the same problem. Tony Stark’s megalomania, Steve Rogers’s patriotism, Bruce Banner’s out-of-control alter ego, Thor’s unruly kin, everyone has contributed to the problem at hand.

The metaphor mutates but does not disappear: SHIELD’s Tesseract-powered weapons are simply a metaphor for what we already have: weapons that humanity has actually developed in order to deal with super-powers, real-life super-powers. The metaphor is suddenly strengthened: in the real world there are real super-powers who really do go around screwing things up for everyone and destroying the world while beating each other up. In this moment, the Avengers become their own worst enemies. They, separately and collectively, have brought disorder to their world.

Now that this storm of agendas has reached its peak, let’s pause for a moment and talk about how The Avengers balances its “superhero” moments.

It begins with Nick Fury, who possesses a kind of power everyone is familiar with: governmental power. Fury commands people, airships, scientists, bureaucrats, resources. It then presents Dr. Selvig, who possesses scientific power, the power to understand the Tesseract, and Loki, who wields a scepter that gives him power over men’s minds but is otherwise a dude in a weird outfit, incapable of flight, super-strength or zapping things. It then sidesteps to Black Widow, who also has power over men’s minds, albeit in a very different way. Then it gives us Tony Stark, who wants to use his powers for good but is kind of a jerk, Steve Rogers, who wants to use his powers for good but is kind of a dork, and Bruce Banner, who doesn’t want to use his powers at all. Finally it gives us Thor, who has incredible power but feels it’s best to withhold it. Each one of these scenes is presented with maximum impact — we feel Fury’s governmental power and Natasha’s psychological power as viscerally as we feel Tony’s technological power or Steve’s physical power. The narrative builds power upon power, it has differently-powered characters first dance with one another, then fight, until Barton, Loki’s slave, returns to free his master, and the narrative cycle begins again. Now that all that power has been presented, tangled and coiled in on itself, it is time, at mid-movie, to express itself.

So the screenplay presents a conflagration, an excuse, really, to let all that coiled energy burst forth. Barton alights on Nick Fury’s gigantic helicarrier and takes out one of its rotors with one arrow strike. It would appear that Barton’s talent is for precision, knowing an enemy’s weak point. It is not a coincidence that Barton strikes at the exact moment when tempers have reached their boiling point among the Avengers; it is, rather, a narrative expression of it. It’s like the moment in a romantic comedy when the lovers argue, then grab each other and kiss: having flexed their muscles for an hour, our gang of heroes now must leap into action with each other.

The scenario breaks into a number of sections. The cynical Tony and the naive Steve are given a technological problem to solve, Natasha is handed a situation with the Hulk that she can’t solve with feminine wiles and must hand things over to Thor, who sees himself as an expert in peace through strength. Nick Fury, meanwhile, contends with the tactical problem of hostile forces invading his ship’s bridge. At the mid-point of the sequence, Fury’s men get the Hulk out of the way, leaving Thor to deal with Loki, who gets the drop on him and, well, drops him, out of the sky in his own prison. Tony and Steve get separated, leaving Tony to deal with the technology and Steve to deal with some soldier work. The action round-robin circles back around to Black Widow, who cures Barton from his Loki-mind-meld with a clonk to the head.

This is all impeccably staged. The technology feels real, the superheroics have heft and impact, the emotions are felt, the human interactions are closely observed. The power wielded by the superheroes is primarily defensive: Iron Man fixes a rotor, Steve fights off some soldiers, Black Widow knocks some sense into Hawkeye, Thor tries to control Hulk. The only people using their powers to attack are the power-hungry, the entranced and the enraged.

Why is the heli-carrier attacked? It actually took me a moment, in retrospect, to understand. The goal is not “to free Loki,” although that happens. It’s not even “to enrage the Hulk,” although that’s floated as a reason. The real reason for the attack is to put Fury’s mega-machine, the flying aircraft-carrier, out of commission, for reasons buried deep within the cinematic syntax of Act I. Fury arrives by helicopter at the secret installation and Capt America arrives by heli-jet at SHIELD’s aircraft carrier, and that aircraft carrier turns out to be a heli-carrier, all of which suggest, cinematically speaking, that Fury is the most powerful character on the chessboard. Loki, in order to have air supremacy in Act III, must cripple Fury’s heli-carrier to make way for the Chitauri’s own weird aircraft.

At the end of this long, complicated roundelay, Agent Coulson dies at the hands of Loki, who escapes on a jet. Coulson has been the fragile human soul of the movie, the “fan,” the audience surrogate, the most easily relatable character. His fanboy admiration of the dorkiest Avenger, Capt America, touches us, because there is a part of us who like to be that simple, that pure, that sure of ourselves.

And so, here at the end-of-Act II low point, Nick Fury, our protagonist, our father figure who has lost his favorite son, finally reveals himself. Yes, he says to Tony and Steve, SHIELD was developing superweapons from the Tesseract, but he has always had his mind on a higher goal: a team, a family greater than the sum of its parts. Those parts are now scattered hither and yon, the Tesseract and Loki are gone.

Toward the beginning of Act III, a security guy gives clothes to Bruce Banner, who has crashed through the roof of a factory or warehouse or something. The security guy is played by Harry Dean Stanton, who, the veteran viewer knows, has seen some weird shit in his day. He asks Bruce if he’s an alien, specifically referencing Alien, where Stanton got his head gored by the eponymous xenomorph.

Back at the heli-carrier we check in with Natasha and Barton. Barton was the first superhero casualty of the screenplay, now he’s the first to be brought around to action again. Barton’s first concern is “How many agents did I kill while I was hypnotized?” As the screenplay has hinted, there are dark aspects to “good guys” having too much power, especially in the world of spycraft. The casting of Jeremy Renner, star of The Hurt Locker, deliberately echoes the message. In that movie he was an adrenaline-mad soldier heedless of collateral damage, and Hawkeye’s arc connects The Avengers to the real world, makes its metaphor clear: if we, the “good guys,” can’t use our power for good, are we still good? Natasha complains of “red in her ledger,” but everyone on the team who has red in his or her ledger. Can ridding the world of Loki wipe it out?

Keep in mind, at this point no one on the good side of the equation really knows about the real villain of the piece, the Chitauri. Is that part of the narrative strategy, to make our heroes rail against the comic villain, the buffoon, expending themselves before unleashing the real villain of the piece? Was that Loki’s goal all along, to sow dissent among the Avengers so that they would be in disarray when it was time to show his true hand? Somehow I doubt it — he’s been caught off guard too many times, he’s been practicing his victory speeches too much. As Coulson says, it’s not in his nature to succeed.

Tony, for his part, does some analysis of Loki’s personality and finds — himself. It is only when Tony sees himself, sees his own vanity and desire for fame that he grasps Loki’s plan — to take over Stark Tower. While Tony, Steve, Natasha and Barton take off for New York and Thor wields his hammer anew, Fury’s sidekick, Maria Hill, chides him for lying to his team — his children — to get them to fight. It’s one of the laudable aspects of The Avengers that, even at its most gung-ho, it finds a moment to keep its protagonist shaded in ambiguity.

Heading into the final battle, Tony’s “red” — his own megalomania — is what he needs to clear from his ledger. Dr. Selvig, still in love with “power itself” in the form of the Tesseract, is opening a portal to the other end of the universe right on top of Tony’s own super-powered building. He cannot destroy the Tesseract, it defends itself at this point, but he could, theoretically, destroy his building, which would send Dr. Selvig’s portal-generating device down into the street. He, of course, cannot do that — ego would not allow him to destroy a building with his name on it. It’s his legacy, his gift to the world.

No, instead of destroying his building, Tony lopes inside and has a chat with Loki. Tony doesn’t acknowledge that an army of aliens is coming, he either doesn’t register it or doesn’t consider it germane to the conversation, which is merely him, one on one, with Loki, whom he neither respects nor fears. Which is, of course, exactly the sort of attitude designed to get Loki riled. Loki may be Thor’s brother, but he’s Tony’s soulmate. Tony’s tete-a-tete with Loki is his own Black Widow moment.

Loki tries to take Tony’s heart with his scepter, but ah, Tony, lest we forget, doesn’t have a heart, or rather, he has a mechanical heart. Tony’s heartlessness, his defining characteristic, here is his saving grace. Loki cannot harm him, at least not in a god-like way. He can, of course, shove him through a plate-glass window and send him to his death, which he does, but of course Tony has a plan for that as well, he has a plan for everything, he’s the Batman of the team. He takes no damage whatsoever from the plunge through the plate-glass window and puts on his super-suit in mid-air, and comes back with a rejoinder for Loki. ”There’s one more guy you pissed off,” he says. ”His name is Phil.” ”Phil,” of course, being Phil Coulson, whose name the screenplay made a point of, 90 minutes or so ago, here in this very room.

The gloves are off, the war is on. Stark Tower is ground zero. For the first time in The Avengers’s narrative, there are civilians involved. Civilians had to pay attention in Stuttgart, but now they are collateral damage.

Why New York, again? Hasn’t New York suffered enough cinematic attacks since 9/11? From the Green Goblin’s assault on the Roosevelt Island tram to Cloverfield‘s giant angry whatsit, to Bane’s perversion of the Occupy movement, why must New York keep suffering? Part of the answer, of course, is that New York must suffer fantastic re-creations of 9/11 in order for us to understand and heal from that event as a culture. Another part of the answer is that New York is simply Marvel’s home and always has been — there are fewer cinematic real-estate shifts more jarring than the one that removed The Punisher from the gritty streets of New York and moved him to — what the – Tampa? But finally, the answer to the question “Why New York?” is that it is America’s City, the melting pot, the place where America, like it or not, was born, and is continually born, the place where all the world comes to be American. Millions of people, all from somewhere else, all living atop one another, all clashing against each other, all chasing the dream, all hating one another, all knowing that that very clashing makes the city stronger. Just like, you know, not to put too fine a point on it, The Avengers.

And you know, if Hollywood wishes to serve up 9/11 movies, perhaps we are better served, culturally, by having light spectacle like The Avengers or silly horror like Cloverfield than on-the-nose, hand-wringing, metaphor-free dramas like Green Zone or Rendition. Messages are always better delivered in shiny envelopes. Audiences avoid movies that are “good for them,” they go to the darkened theater to dream, not to be instructed. Which is, after all, what makes a movie a movie and not a novel or a lecture or a TV show: a movie is constructed like a dream, disparate images butted up against one another, the sense made by the viewer. It’s all imaginary, and we know that it’s all imaginary, which is how we let it in.

Which makes this as good a place as any for me to tip my hat to Mr. Joss Whedon, who, lest the reader forget, has never really directed a movie before this. Plenty of television, yea verily, but television is not the movies, and his accomplishment here is astounding. Having written a handful of comics/superheroes/fantasy screenplays of my own, I can attest: it is impossible. It is impossible to serve all the needs of the comics-based superhero narrative, while fitting the needs of budget, the demands of “the fans,” the demands of the studio and the demands of cinematic narrative. That is why so many superhero movies fail. And yet, Whedon here succeeds – spectacularly — with a cinematic narrative that presents seven – seven! — superhero arcs and lands them all with grace, panache and great good humor. The Dark Knight is the only other screenplay to successfully pull off a cogent, coherent superhero narrative before this — now imagine if that movie was also funny, nimble and had a sense of its own silliness? Imagine if, at some point in The Dark Knight Rises, Selina Kyle turned to Batman and said “Really? Growly voice?” Or, imagine The Dark Knight Rises with Tony Stark in Bruce Wayne’s place. And why not? They’re both genius billionaire industrialists with an eye for gadgets.

The battle sequence that caps The Avengers is ferociously complicated and it bears study for its ability to balance plot, theme, character and story. As I’ve said, it begins with Tony Stark confronting Loki as a mirror. If all the Avengers want to “wipe the red from their ledger,” Tony’s red is his ego. He succeeds in his first blow, insofar as he strikes it for Agent Coulson instead of for himself (although he stops short of destroying his own penthouse apartment for the sake of toppling the Tesseract’s portal-generator).

Loki’s response to Tony’s blow (although it was always going to happen) is to let through the Chitauri. Tony, being a one-man army, now faces a multi-man army. He has the tools to defend, but the Chitauri are many.

Luckily, Thor now shows up to battle Loki atop Stark Tower mano-a-mano, allowing Tony to concentrate on the Chitauri. Which is apt: Tony “won” his war against Loki when he struck a blow for Agent Coulson, but Thor’s battle has just begun. (How Thor knew to find Loki in midtown Manhattan is another question.)

Next, Natasha, Barton and Capt America enter the fray, in a SHIELD jet. Being all, essentially, soldiers, they join in Iron Man’s fight in the skies against the swarming Chitauri. They almost immediately fail and crash (into the plaza of The Clamp Building, the location for Gremlins 2, for those keeping score).

The first round of the battle ends as the earthbound trio are confronted by the massive whatsit Chitauri flying spinal-column thing, which spawns Chitauri like fleas off a dog’s back. With no SHIELD heli-carrier in sight as an aerial counter-weight, everyone is taken aback by this, including Loki, who suddenly realizes that he’s been played for a fool, that the Chitauri (or The Other, or the mysterious unnamed boss at the other end of the universe) have no intention of leaving an Earth worthy of Loki’s rule. This almost, but not quite, leads Loki to a change of heart. He knows he’s been had now, but that doesn’t lessen his need for respect, or for fear.

Unable to beat Thor, or face his foolishness, Loki catches a ride on a passing Chitauri jet-ski and proceeds to blow up a chunk of Park Avenue. The flying spinal-column troop transport ship has taken the skies over midtown, now Loki takes to the streets. Goodness knows how many casualties there are in the midtown area at this point, but the movie doesn’t pause to mourn the dead or wounded, so, in action-movie language, there aren’t any. Cars fly and building facades shatter, but no victims burn, fall or splat. In action-movie language, property damage is awesome but loss of life is a bummer.

With three of its heroes earthbound, the narrative hands them a rescue mission: get some people out of a bus. Why? Why not keep the SHIELD jet in the air, so our guys could blast aliens out of the sky? Well, it keeps the battle raging on multiple levels, and it also makes an important narrative point, one that often goes ignored in superhero narratives: the bad guys have to be after something other than the good guys, and the good guys have to defend something other than themselves. Bruce Wayne has to defend Gotham, not merely address his prepubescent trauma, although it helps if he can do both.

We check in with Natasha and Barton, the two spies, who share a moment of camaraderie, or what passes for it among spies. Hawkeye, to some extent, is the red in Black Widow’s ledger, and the two of them now reconcile the way SHIELD agents do: by working together to pick off some horrible aliens.

Capt America stops to give orders to a police officer. The officer, who is unfamiliar with Capt America, balks. Why? The movie could have easily made the officer a Coulson type, a “fan,” but instead it plays the “cynical NY cop” card. The screenplay wants to remind us that Capt America has an image problem because he is, let’s face it, a boy scout, a do-gooder and kind of a dork. If only the nation he represents had the same qualities in the 21st century! And yet, here on the beleaguered streets of Manhattan, Capt America is living up to the hype. He isn’t a technological genius like Tony Stark, he doesn’t have blood in the battle like Thor and he’s not a duplicitous spy like Black Widow or Hawkeye: he’s a street-level defender of the innocent, which gains the cop’s, and our, respect. Capt America’s anachronism is the red in his ledger, and “defending the innocent” is his answer: after all that has changed in America, that’s still what he’s good at.

Thor joins the earthbound trio in the street, and they realize that they are a necessary lightning-rod of the battle. Without them, the Chitauri will run rampant over the city. (It took me a while to realize the Chitauri’s endgame. They don’t want “to destroy the world” necessarily, they merely want to nab the Tesseract, which means they don’t need to destroy the world or even Manhattan, they just need the time and space to get the Tesseract, which they can’t do while there’s a bunch of superheroes fighting them.)

At this point, Bruce shows up on a puttering moped and offers to join in. He says to Capt America that his secret is “I’m always angry,” which both turns conventional Hulk wisdom on its head and suggests another, previously-ignored aspect to Bruce’s personality. If Bruce Banner is “always angry,” why does he do what he does? Does he travel to India to help the sick because he is “always angry” about the way poor people don’t have access to medical care? Does he come to Fury’s helicarrier to help find the Tesseract because he is “always angry” about tyranny? The point seems to be, if Bruce is “always angry,” then the Hulk is an expression of something else, or a controlled response to extreme stimuli. It is something he wills into being. Self-control is Bruce’s red, and his will-of-the-Hulk is his ledger.

In any case, the Hulk brings down the Big Flying Whatsit with one punch, and the battle moves into its next phase.

Now that the Avengers have “cleared the red from their ledgers,” the real battle for New York, and the world, begins. Capt America, the living anachronism, is suddenly made commander. Why is unclear: he’s shown no flair for either strategy or tactics up to this point, and he’s eternally baffled by technology. He is, however, the group’s resident idealist, and Coulson’s favorite, which gives him the moral edge. Nick Fury, it’s worth mentioning, is absent from the battle. He is, I hesitate to say, the “real power” at this point, governmental power the way we mortals understand it: sneaky, underhanded and secretive, no matter how high his ideals.

Capt America sends Iron Man and Hawkeye up top to call the game and take out aerial threats. He sends Thor to bottleneck the portal and keeps Natasha at his side for hand-to-hand combat. Hulk he sends to “smash.” That is to say, Hawkeye will act as a lookout (his forte), Iron Man will act as a weapon (his heritage) Thor will act as thunder-god (his very name), he and Black Widow will work the fight on the ground (turning their limitation into a strength) and Hulk will wreak havoc (his secret thrill). (Bruce, after enduring an act of Tony Stark’s ribbing about his lack of self-control, now has the last laugh: he enjoys hulking out.)

Thor (somehow) uses his hammer to turn the Chrysler Building into a lightning rod (to the surprise, I’m sure, of the thousands of people currently in the Chrysler Building) and then (somehow) uses the ensuing lightning as a kind of lightning-sphincter on the Tesseract portal.

Meanwhile, up in the heli-carrier, Fury is called to the Council. The Council, as Councils will, wishes Fury to annihilate Manhattan with a nuclear strike. (The Councils two speaking members are Powers Boothe and Jenny Agutter. Powers Boothe came to fame playing the Rev Jim Jones in a TV movie about Jonestown, Ms. Agutter is known for being “the girlfriend” in Logan’s Run and American Werewolf, but came to prominence as “The Girl” in Nick Roeg’s Walkabout. If there is a specific movie-movie Whedonverse joke in their casting, it escapes me.)

In the streets, Hawkeye directs Iron Man to exploit the Chitauri glider’s weakness in turning skills (a purely mechanical flaw) while Black Widow learns where the Chitauri armor is vulnerable. Again, the fighting style is suited to the character. The Chitauri, it should be noted, remain utterly without ideology. They don’t even reflect Loki’s megalomania, they’re merely an anonymous “threat” of the “Crush, Kill, Destroy” variety. Nor, it should be said, do they have a mind-bending or confounding technology, like the Martians in War of the Worlds. They have machines and armor, but their machines have understandable limitations and their armor is not magical. They are, all in all, an easily understood, easily hated enemy, without metaphor, the better to flex against for the good of humankind.

Natasha now steps out of her comfort zone to manipulate the Chitauris in ways she hasn’t yet manipulated men: at high speeds over city streets. She hijacks a glider and “pilots” the pilot with knives to his ribs. In the ensuing incredible shot, we see a virtual tag-team of heroics as Black Widow pilots, Iron Man teams up with Capt America to zap, Hawkeye pierces (100 internet dollars to those who understand that as a MASH reference), Hulk pulverizes and Thor hammers. Hulk, just to keep things lively, also punches Thor out of frame: Bruce in complete control is no longer Bruce.

In the street, the US Army arrives to help out. Depending on your view, this either helps or hurts the cause, but is another nod to the political dimension of the movie: “the real heroes” of the events that inspired the narrative.

Meanwhile, atop Stark Tower, Dr. Selvig, although he has not been conked on the head by Natasha, nevertheless comes out of his Loki trance.

In a nearby bank, the Chitauri have cornered a number of civilians, causing Capt America to come rescue them. Is there a metaphor at work, that Capt America must save citizens trapped in a bank? Are the Chitauri now predatory lenders, and their blinking blue grenade a low-interest Adjustable Rate Mortgage? Whatever the metaphorical import, the encounter in the bank leaves Capt America shaken, to the point where civilian passers-by look at him with pity.

Up in the sky, Black Widow is in over her head, so to speak. Loki is after her on his own glider, but Hawkeye, watching her back, knocks him out of the air with a well-placed arrow, depositing him right where we began, on Tony Stark’s porch, where the Hulk, having the last word, shows up to make short work of the god who would be king.