.

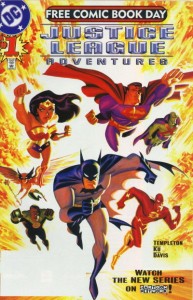

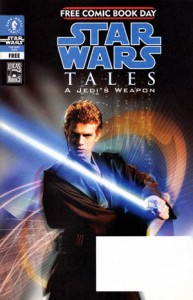

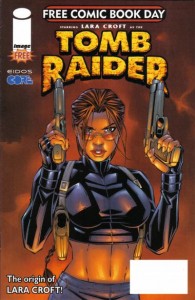

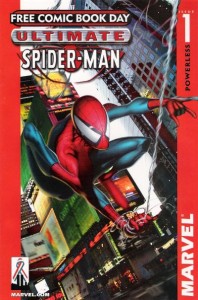

(The first four Free Comic Book Day titles, 2002)

May 6, 2011, marked the tenth annual celebration of Free Comic Book Day (FCBD). Now considered a “national holiday” among comics fans and retailers, FCBD has been an incredible marketing success, encouraging the general public (and fans) to visit comics shops on the first Saturday in May, and allowing publishers big and small to promote a diversity of titles which might otherwise be ignored.

Ten years is both a long, and short, time in human history. Long in foresight as we view the time ahead, wondering “what if…”, dreaming of possibilities, and sometimes dreading the challenges to be faced. Ten years in retrospection, that passes quickly, as we look back and wonder at when we’ve been, could it really be ten years ago? Ten-year anniversaries are largely ignored by the general media. They prefer twenty-year anniversaries, as nostalgia seduces the old with remembrance and the young with the unseen.

Yet ten years is a long period of time. In comics publishing, that equals 120 monthly issues, a figure most titles rarely approach. For daily comic strips, that results in over 3600 strips! For fans, that can mean 500 visits to their local comics shop, wandering the aisles looking for something interesting, chatting with the employees, and spending thousands of dollars enjoying what the general public considers to be a rather disposable art form.

For us comixologists, who spend time analyzing the history and culture of comics and graphic novels, we try to classify and analyze the Big Picture ( Splash Page?). Is the market cyclical? Does the latest ripple from Brand X recall a similar event from a previous, long-gone publisher? Where were we when… and how do we react now to what was then?

In the ten years following Spider-Man, multiple comics properties have been adapted to the Silver Screen. Where once there might be only one comics-based film a year to look forward to (such as Howard the Duck or Supergirl), now there is, on average, a movie a month, as the Summer blockbuster season features a movie every two weeks, with more scheduled for the winter holiday at the end of the year. As superhero movies become popular and lucrative, they inspire original works in film and television. The general public understands the genre conventions of a superhero. Weekly series explore the “real world” of superheroes, and independent filmmakers mix the marvelous with the mundane, creating original works. Just as a silent Spider-Man on the Electric Company encouraged a young boy from Omaha to read and dream about superheroes thirty-five years ago, so does every episode on television and every screening in a Cineplex tempt children to wonder, “What happens next?”

Which brings me to the third connection: graphic novels.

For bookstores and libraries, books about comics, and collections of comic books were considered curiosities, generally shunted off to collectibles, or humor, or science fiction (if the store stocked the books at all). Libraries might have a shelf of titles located next to the books on drawing, but these were usually New Yorker collections, how-to-draw instructionals, a few comic strip collections, and the rare history of the art form. Libraries were hesitant to shelve titles not reviewed by literary magazines, and major reviews for books about comics were about as rare as comic book movies. While comics were stereotyped as popular culture (at best) or disposable pulp (at worst), part of the problem was that there were few comics worthy of review.

This changed in the mid-1980s, as Maus, The Dark Knight Returns, and Watchmen were published. Art Spiegelman, the author of Maus, was influenced by the underground comics movement of the 1960s and 1970s. His stories were published and sold not via comics shops, but thorough the literary and artistic communities. The chapters were then collected into a book, and marketed by Random House’s Pantheon imprint. A comic book about the Holocaust, with the characters depicted as animals, telling the author’s experience with his father, a holocaust survivor, gained tremendous press, and eventually was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize.

Bookstores continued to stock and sell the occasional graphic novel, usually displayed in the Humor section next to the more popular comic strip collections. Comics publishers continued to offer trade collections for sales to libraries and bookstores, although the bulk of the sales were via comics shops.

So, by May 2002, there were numerous publishers offering graphic novel titles to the bookstore trade. Some were established publishers such as Dark Horse, DC, Marvel, and Viz, while others were newcomers such as Lerner and Capstone. With the increased interest among booksellers and librarians, BookExpo America created a Graphic Novel pavilion, showcasing graphic novels and comics in a dedicated area of the show floor in New York City.

Unlike the boom and bust of the 1980s, the popularity of graphic novels in the new millennium has not waned. Educators praise the seductive quality of comics with reluctant readers and non-native speakers. Librarians appreciate the high circulation figures of manga and comics, as well as the ability to attract teens to engage with reading clubs and advisory groups. (Yes, librarians actually ask their patrons which series they should acquire!) Bookstores value the popularity of any pop-culture book, especially those which are adapted into critically-acclaimed movies. As each generation becomes more acclimatized to comics, older prejudices die out, and new creativity flourishes.

So, the synchroneity of Spider-Man, BookExpo America, and Free Comic Book Day marked a significant turning point in the history of American comics. While all three events were marketed to different audiences, they all helped make a more popular and accepted medium. Ten years later, it is easy to look back and notice the changes inspired by these three simple events.

Comic book stores are more diverse and professional, supported by the visionary leadership of ComicsPro and the Comic Book Industry Alliance. Library organizations honor graphic novels not as comics, but as worthwhile literature, suitable for all libraries. Educators champion the unique qualities of comics, not just in schools and classrooms, but also at conferences around the world. Bookstores market comics to those who love to read, and to those who search for new ideas regardless of media. Movie companies spend millions of dollars advertising movies based on comic books, which serves to advertise comics worldwide (as proven by the Watchmen movie trailer which preceded The Dark Knight).

So what do the next ten years offer? This year might be pivotal as well, as various initiatives and possibilities foreshadow and overshadow the Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow… In the meantime, I’ve got some free comics to read!

Great summary. I might suggest a mention about Dark Horse Digital Comics, which launched around the same time and which also published their FCBD in digital format.

Librarians were acquiring – and promoting – graphic novels and comics since before the 1980s. I started in 1983, when I started working in a public library. By 2002, with the Young Adult Library Services Association Preconference, “Getting Graphic @ the Library,” speakers Art Spiegelman, Neil Gaiman, Jeff Smith, and Colleen Doran were surprised at how many librarians already knew who they were, already had their books in the library, and treated them like rock stars. These were, of course, young adult librarians – librarians who work with teens. Some librarians worked with their local comics shops to have FCBD programs in their libraries for the first FCBD.

You are correct, Kat. I neglected to mention the precedence of librarians such as yourself and others, including Rory Root.

The ALA conference was late May?

Has anyone written an evolutionary timeline of comics and libraries/schools?

When I left Omaha (and my student position at OPL) in 1994, the comics were all non-fiction, and occupied two shelves at the main library, and fewer at the eight branches. I suspect other libraries had similar collections. When did it shift? Probably when more publishers entered the book trade, and Pantheon restarted their GN line, circa 1997.

“After the disastrous speculator collapse triggered by the return of Superman in Adventures of Superman #500”

I’ve never heard the speculator collapse so directly identified with a single issue before. What’s the story there?

I also remember the collapse coming after the sporging of chase-cover variants and the multi-million print runs of the original Image lines and new Marvel #1’s that left retailers with hundreds of unsellable collector’s items per customer.

No one inside comics was fooled by the Superman death story. That was all about tricking people who didn’t buy comics into buying that one.

The mention of Superman 500 caught my eye. Musty copies, still in their original plastic seal, were handed out here on FCBD.

I opened and read my copy at home, then promptly wrapped it in plastic again to avoid the HazMat team. Then I sailed it into the recycling bin.

I was shocked (sHoCkEd, I tell ya) at how bad the story and art was, but maybe that’s ancient history to everyone else here.

“I’ve never heard the speculator collapse so directly identified with a single issue before. What’s the story there?”

The Death of Superman occurred on a “slow news day”, which meant that numerous news sources reported on the event. Retailers were caught unprepared for the demand from the general public. Not wanting to be caught unawares, many stores over-ordered on the “return” issue, speculating on the speculators.

Here’s CBG’s analysis:

http://cbgxtra.com/frequently-asked-questions/when-did-the-early-1990s-comics-boom-peak