Like every form of entertainment, comics have looked for ways to take advantage of the arrival of the digital age. In addition to making comics available to read electronically, the industry has created content that was only achievable in a digital format.

One of the earliest attempts was motion comics, but they failed to take off. Neither comic book readers nor cartoon fans were interested in seeing great comics chopped together into a crude form of animation. The format hung around as publishers continually tried to make them work. But, despite high-profile efforts like Brian Bendis and Alex Maleev‘s 2009 Spider-Woman series, motion comics more or less petered out.

Around the beginning of the last decade, a new made-for-digital comics format started to gain prominence, though they still don’t have a universally recognized title. For the purposes of this feature, I chose to refer to them as infinite comics. That’s the title Marvel used for its line of made-for-digital series, and the term represents the format’s lack of restrictions compared to traditional comics.

In the beginning, infinite comics generated a lot of excitement, at least on the publishers’ end. They were first introduced to North American audiences through Alex De Campi and Christine Larsen‘s Valentine. The next several years saw the release of dozens of new titles and the launch of Thrillbent, a publisher that solely produced infinite comics. But the format is now a shell of what it once was, which is a shame because the format does a lot of new things while staying true to the fundamentals of comic book storytelling.

As a big fan of the format, I decided to take an in-depth look into the short history of infinite comics, with insight from four of the creators leading the charge.

Storytelling Innovations

For readers who have never read anything in the made-for-digital format, infinite comics use a kind of flip-book effect through the use of layers in Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. Every tap changes what you see on the screen, sometimes in big ways and sometimes more subtly.

When they first debuted, some critics likened infinite comics to motion comics. However, unlike motion comics, infinite comics hold on to what makes comics unique from every other visual medium: the unique control the reader has over its pacing. And, while infinite comics only show one image at a time, the format still feels like sequential storytelling because of how elements are added and removed from each screen.

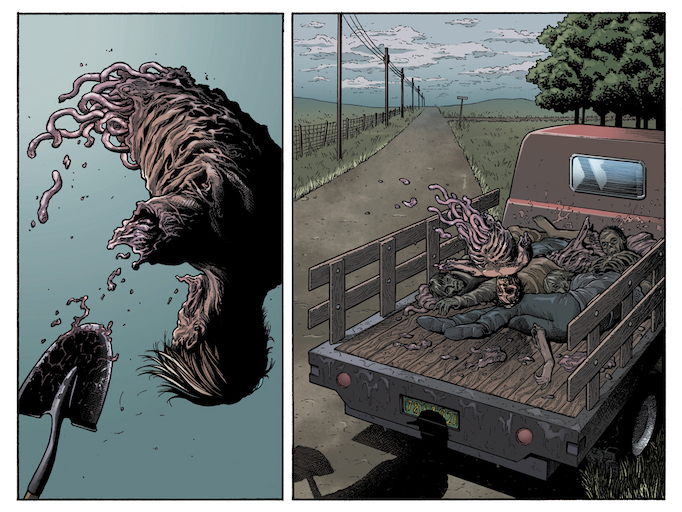

Valentine is a series about soldiers in 1812 lost in the snow following Napoleon’s retreat from Russia, who discover horrors they never expected to find. As well as being the first infinite comic, it’s one of the longest series ever published in the format. Nineteen issues have released, with the final two issues on the way.

Reading the series you can see De Campi and Larsen become increasingly adept with the new form of storytelling as they pioneer it. Larsen said that she enjoys how the format gives the creator more control over how the story unfolds to the reader:

I think doing the long, rollover panels was really interesting. That’s not something you can do much of on a comic page. It was also really good for “reveals”. A sudden monster popping out or a slow unveiling of a scene that might be more intuitive to motion storytelling could work really well in digital format.

Another solid introduction to infinite comics is Thrillbent’s first title Luther, a one-and-done zombie story written by Mark Waid and illustrated by Jeremy Rock and Robt Snyder, which you can read for free here. The purest way to experience the comic is via Thrillbent’s website or on a tablet but, if you prefer to stay on this site, the below series of images gives you an idea of how the format works.

Waid explained what so excites him about infinite comics:

It uses the medium. Most digital comics are just pictures of comics. Digital allows for so, so much more innovation. As far as I was concerned, what we’d developed was an entirely new hybrid medium that I couldn’t wait to play with. The ability to play with the interaction of pictures and text, the ability to use layout as an even more dynamic storytelling tool… it still gets me revved up.

In some cases, infinite comics produce more of an impact than traditional comics. As someone involved in the production of the majority of the series published by Thrillbent, letterer Troy Peteri has unique insight into their creative process. He told me about some of his favorite uses of the format he encountered.

I really enjoyed how the strips utilized the “swipe” method for humor and horror. We’re all used to a cliffhanger […] on the bottom right panel of a comic that makes the reader want to turn the page. But just swiping on a phone or tablet can give a reader many instances of stuff that’s harder to pull off in a traditional turning of the page, like “jump scares” or repetitive sight gags.

For example, if you have a horror comic and there’s a character getting ready to open a door without knowing what’s on the other side, the last panel of the page would have the character with their hand on the door. When you turn the page, maybe there’s a sudden splash page of something horrific behind the door. But you only get the one static image of what’s behind the door. If you swipe at the last panel and you see the thing that’s horrific, and then you swipe it again and the villain inches closer to you. Swipe it again and it’s a tight close-up, swipe it again and it’s just a panel of splashing blood or whatever. That gives you a sense of motion and action and tension that’s harder to replicate in a traditional comic, but it doesn’t feel as much like you’re just watching a motion comic with limited animation.

The Eight Seal, a horror political thriller from James Tynion IV and Jeremy Rock, is one of the most impressive Thrillbent series because of its ability to induce jump scares.

Even superstar comic book author Brian Bendis wrote four Infinite Comics tie-ins for his Guardians of the Galaxy run. During an episode of the Word Balloon podcast, he pointed out how the format eliminates the limitations of double-page spreads in digital comics. He said that he believes a splash in an infinite comic, which encompasses the tablet’s entire screen, achieves a similar impact to double-page spreads in print comics.

Origins of the made-for-digital format

The digital comic format’s origins trace back to the French cartoonist Balak, who referred to it as turbomedia, a moniker that never reached the North American comics lexicon. Balak began publishing turbomedia comics on Catsuka.com. He even created a comic that illustrates what makes infinite comics special.

Mark Waid’s first encounter with infinite comics was Balak’s work:

Back when I was an executive at BOOM!, I was eternally frustrated by the fact that comics printing costs were so high and such a huge cut into a publisher’s potential profit margin. The goal was to flip the paradigm–find a way to make money on digital first, where there are no print costs, then repackage for print once a profit is realized. So I went surfing the web, looking at existing webcomics, and stumbled across the work of the French cartoonist Balak. I was floored. Balak, so far as I’m concerned, is the Orson Welles of digital comics, transforming the entire medium with innovative thinking. He lit the spark.

Around the same time, Joe Quesada recruited Balak to establish Marvel’s Infinite Comics line.

Years ahead of Waid and Marvel, Alex De Campi began self-publishing Valentine on ComiXology in 2009. The series generated a lot of enthusiasm, topping 500,000 downloads. De Campi shared that, in a lot of ways, the popularity of Valentine relaunched her career. Its success further emboldened Marvel and Waid to pursue the new form of comic book storytelling.

Large publishers enter the field

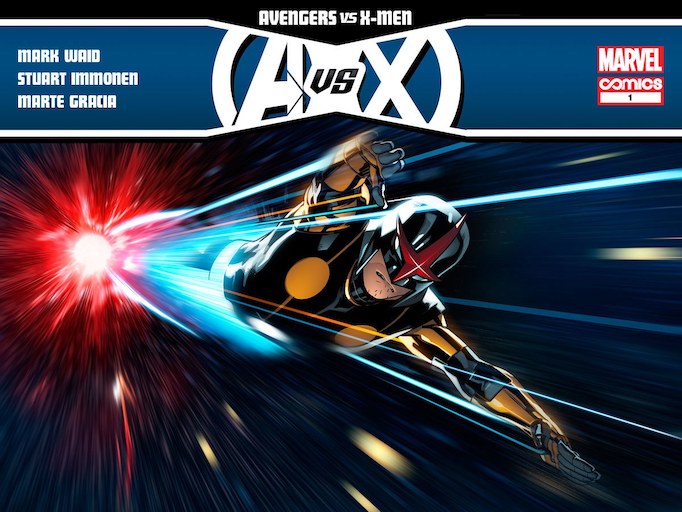

The first infinite comic Mark Waid created was Luther, which he originally shared through his personal website on March 16, 2012. His first non-self-published infinite comic was Avengers vs. X-Men #1: Infinite, released on ComiXology February 29.

The tie-in to the year’s big Marvel event features superhero Nova flying through space, warning the Earth of the return of the Phoenix Force. Written by Waid and illustrated by Stuart Immonen & Marte Garcia, it was an epic introduction to a new kind of comic book storytelling.

Waid was so impressed by the digital format that he sold his comic book collection to help fund Thrillbent, a publisher devoted to publishing infinite comics. It was especially meaningful for a creator known for his deep respect for and knowledge of comic book history to invest in a new kind of comic book storytelling.

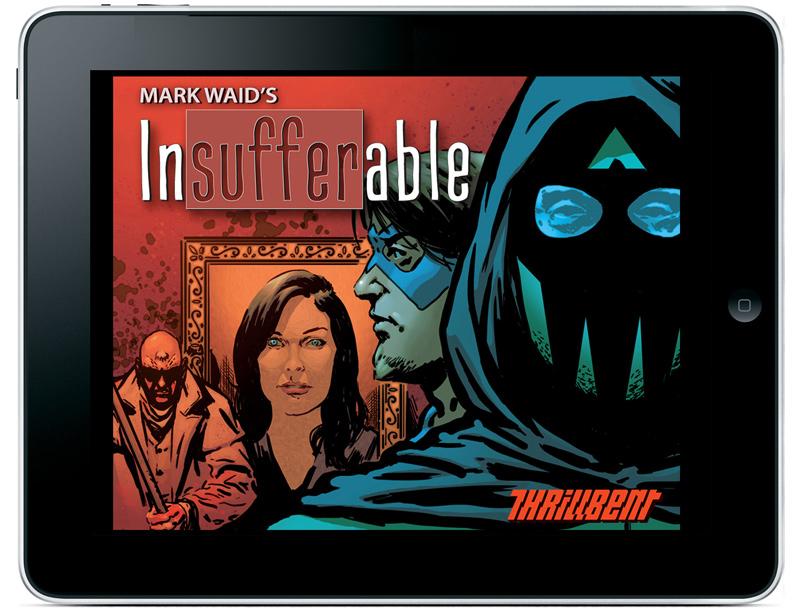

On May 1, Waid and co-founder John Rogers officially launched Thrillbent. The publisher’s marquee title was Insufferable, a comic about a superhero and his unbearable sidekick written by Waid and illustrated by Peter Krause.

Waid decided to stick with a genre he felt comfortable writing while letting other creators tackle different types of stories. Tynion IV and Rock created the aforementioned The Eighth Seal. Rogers wrote Arcanum, a series about magic infiltrating the modern world illustrated by Todd Harris. Christina Blanch, Chris Carr, and Chee created The Damnation of Charlie Wormwood, a crime drama about a teacher at a prison forced to make desperate choices to save his dying son. Thrillbent even became the home of new episodes of Valentine. Those are just a few examples of the dozens of titles Thrillbent published over its lifespan.

Other than Thrillbent, Marvel was the biggest champion of the format, publishing record number of series under the Infinite Comics banner and putting a lot of talent behind them. Waid returned to create Daredevil: Road Warrior with his Insufferable collaborator Peter Krause. In addition to those already named, well-known creators who contributed to the Infinite Comics line include Jason Aaron, Jason Latour, Kieron Gillen, Al Ewing, Ming Doyle, Michael Del Mundo, and Paco Diaz, among others.

DC dipped its toes in the digital format with the DC² initiative but mostly focused on more straightforward digital-first titles like Legends of the Dark Knight and Adventures of Superman. When reading those comics on a tablet every page encompassed an entire screen, but artists actually drew pages in conventional comic book dimensions, designing them so they could easily be split in half. See an example of that below from the first issue of Legends of the Dark Knight.

Instead of putting its resources towards more experimental storytelling, DC chose a less ambitious strategy for its digital content, but one that was also much less cumbersome. Adapting infinite comics to print proved surprisingly challenging and time-consuming.

Altering infinite comics to fit traditional comic book formatting removed what made them unique, but doing so seemed like a necessary sacrifice, considering less than 10% of comic sales are through digital platforms. Waid knew he wanted to repackage Thrillbent comics into print editions to make them available to wider audiences, but didn’t predict how labor-intensive the process would be:

When Dynamite print-published THE DAMNATION OF CHARLIE WORMWOOD, I literally had to print out each screen and take scissors and tape to it all to re-paste and create new layouts that preserved all the original content, then recreate it with repurposed art on Photoshop. I spent an ungodly amount of time producing print files, which was the price of not simply digitally publishing static half-pages.

For the infinite format to be financially feasible, a revered comic book writer had to put together a comic (made by other creators, no less) with scissors and tape.

Christine Larsen echoed Waid’s description of how time-consuming the process could be, explaining that when drawing the issue she is essentially creating a storyboard. An episode of Valentine took significantly longer to complete than a normal comic book issue.

Troy Peteri said that the amount of work required to letter an infinite comic was difficult to predict, fluctuating wildly depending on the project.

In some instances, the comics were considerably faster than working on a traditional comic, but some others were like lettering multiple issues of a traditional comic! So there were some strips I enjoyed working on more than others.

Peteri explained that the learning curve for making infinite comics was fairly steep because he was collaborating with creators who oftentimes had no prior experience with the new method of storytelling. The team had to wrestle with the dimensions of the page, the proper resolution, the differences in scripting, and so on.

In order to combat that challenge, many of Marvel’s Infinite Comics credit a layout artist who determined how to design the pages for the Infinite format. A separate artist would draw the line art using the predetermined layouts.

While Peteri enjoyed the challenge presented by his Thrillbent work and learning to problem solve, those elements of the job made the process more labor-intensive. As a result, developing in the infinite format could be more costly than making comics conventionally if the letterer charges based on how time-consuming the project is.

The format fades away

Thrillbent hasn’t published new comics since 2016 and the shop on its website is no longer functional. Marvel’s last Infinite Comics series was Doctor Strange/Punisher: Magic Bullets in 2017. Even the ComiXology Originals line doesn’t produce infinite comics, despite being created by and for a digital platform. An entire art form (or at least a variation of an art form) has been left behind.

Waid believes Thrillbent’s struggle to become profitable came down to time, not just to create the comics but to promote them.

The slowdown is 100% the result of John and I both becoming insanely busy with other endeavors, unable to put the energy into the site that it needs to grow. John’s a well-known and well-respected TV producer and writer–check IMDB–and I write nine comics a week, so that’s really what it’s all been about. But it’s still a site we’re getting back to sooner than later.

In Waid’s eyes, a broad audience didn’t embrace infinite comics because Thrillbent, the publisher leading the charge, didn’t have the resources to promote itself as much as it needed to.

A startup site, especially one doing something that no one else is doing or has done, requires an inhuman amount of attention, care, and promotion. There are still far too many comics readers never exposed to it – and everyone who samples it gets it and wants to know when we’re going to make more.

Waid also thinks no one’s found a sufficient way to monetize infinite comics.

It all comes down to monetization. When done right, it’s a labor-intensive process, more so than a standard comics page, and no one’s yet found the critical mass readership they need. Or, if we’re talking just about straight-up Comixology-type services, again, it’s down to money (charging the same for a digital comic as a print one) and content (even the best subscription all-you-can-eat models don’t/can’t include Marvel and DC, the titans that drive the industry).

His original idea was to “start with free content and then move to either a premium subscription model or a pay-what-you-will model.” He remains a big fan of the strategy.

If you properly package, promote and publicize your online material to create a dedicated army of fans, I’m firmly of the belief that that model is sustainable.

De Campi believes a key problem was that Comixology never really supported infinite comics as an independent storytelling method.

There was a time early on where Comixology could very naturally have become what Webtoons eventually did, by creating a differently-branded indie comics app that allowed people to self-publish digital-native comics in Guided View and not have them buried in with the deluge of direct-market comics on its main site.

Comixology Guided View certainly supports a lot more innovative storytelling and more interesting choices than the Webtoons vertical scroll, but I think we all have to accept now that Comixology is just the digital version of the direct market / Diamond and that’s alll it will ever be. It’s very good at that, but as a publishing person and a big-ideas person, I look at Comixology and think of all the other cool things it could have done too.

Because ComiXology was primarily concerned with selling comics made for the Direct Market, the digital publisher ignored the opportunity to create a space for indie comics, leaving room for other companies to fulfill that need.

The legacy of infinite comics

Despite the absence of the new material, readers have access to a lot of interesting comics that were published in the format’s heyday. All of Marvel’s Infinite Comics are available via ComiXology. Thrillbent’s website serves as a wonderful archive of the format, especially now that all the series are free to read. However, when reading them online, there’s a slight lag between pages, which lessens the comics’ desired impact. The best way to read the series is by purchasing them on ComiXology, though only a handful of Thrillbent’s titles are available.

Troy Peteri is the co-creator of an upcoming webcomic with Dave Lanphear that incorporates some of the techniques he learned from his time at Thrillbent. The co-owners of A Larger World Studio are developing several webcomics scheduled to launch later this year.

Creators are still making comics designed for digital consumption. Webtoons is a phenomenon many times the size of infinite comics even at their heyday, with 15 million readers daily and 100 billion views annually on the English version alone. Webtoons publishes comics that are on one long, vertical strip, using the “infinite canvas” Scott McCloud predicted in Reinventing Comics. David Harper wrote a feature on his website SKTCHD covering the rise of Webtoons, where he reported that the top creators earn upwards of $10,000 a month just for publishing their work digitally through the platform. Webtoons’ massive success proves that there’s an appetite for unique-to-digital comics, audiences just appear to prefer the vertical strip style to the infinite format.

De Campi doesn’t think infinite comics will ever see a resurgence. She doesn’t like that the vertical scroll format beat out infinite comics because its storytelling options are more limited, but she’s accepted that Webtoons won. De Campi described how the popularity of Webtoons dwarfs not just infinite comics but the entire direct market.

The top Marvel comic in 2019 was hyped to sell 1 million copies and only sold a little over 200,000. The top 30 comics on Webtoons last year had between 299 MILLION views (Lore of Olympus, #1) and 2.5 million views (Wraith & the Dawn, #30).

The numbers are staggering, and undeniable proof of Webtoons’ popularity and position as one of the dominant forms of comic book consumption and storytelling. Still, I’m a little more bullish on the future of infinite comics than De Campi. Not as a business, no. They’re unlikely to ever hit the mainstream status necessary to build an industry around them. But the format remains incredibly innovative and offers unique possibilities for a different kind of comic book storytelling. Creators will always strive for a fresh, exciting way to tell their stories. For the time being, the existing library of infinite comics (plus the upcoming final two issues of Valentine!) serves as a valuable reminder of the versatility of comics.

Thanks to Alex De Campi, Christine Larsen, Troy Peteri, and Mark Waid for contributing their insight to this piece. Some quotes have been edited for clarity.

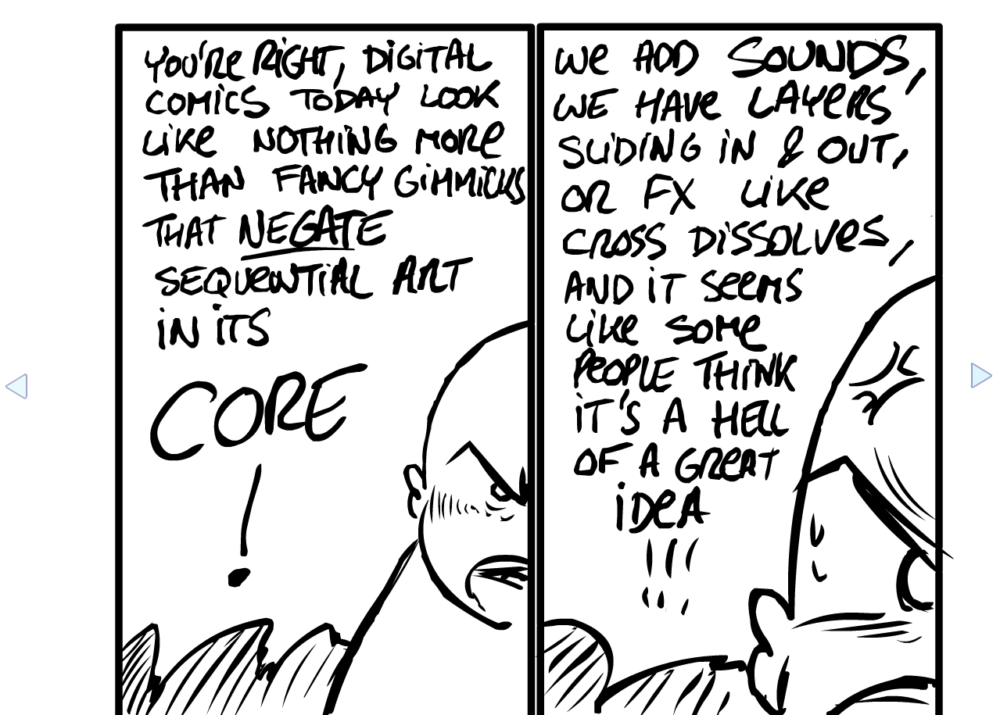

I don’t mean to be negative about everything that isn’t as old as myself, but I consider these augmented comics to be a daft idea. Comics are great, BECAUSE they have borders and do not move. They don’t need touch screens or electricity. Anything you try to add to ink on paper will just pollute it. Granted, this view is treating comics as art, and that might not be everybody’s main obsession, but that happens to be my preference. I’m not saying you cannot make art on an IPad. Sure you can, just do not call it comics…

Having a platform like Webtoons is great for young creators, of course. I just wonder how many people would view them if they weren’t almost all for free.

Comments are closed.