As a kid, it’s easy to disconnect from reality. Your database of experience is low, so you don’t have the visceral experience or memory to question what appears on television, at the local theater, or on the pages of a book. (Of course, you still cry thinking about Dan and Ann, even though Third Grade was so long ago.)

You read an issue of the Fantastic Four where Terrax the Tamer levitates Manhattan Island into outer space, and don’t really notice when he depressurizes the upper floors of the World Trade Center. Other Marvel heroes race to deal with the bridges and tunnels, the tidal action caused by a massive Manhattan-sized hole, but no one ever talks of casualties in comic books. Years later, when Doctor Doom destroys the Baxter Building, when tenants berate Reed Richards for their loss, you don’t connect it to reality, because, really, nobody blows up buildings in 1985.

Until 1994, I didn’t make those connections. Sure, as a kid, I sometimes had power fantasies, usually involving the school bully or the cute girl in my math class. Sometimes I’d nitpick a plot point or hole in a movie or TV show. But mostly, I escaped into make believe, forgetting the world around me, instead of letting it remind me.

But then I moved to Washington, DC in the summer of ’94. Yes, there is a unique bubble of reality inside the Beltway, as many people share a common way of thinking. I read the Washington Post each day, and soon I could recall almost every Cabinet official and a quarter of the members of Congress. Many buildings had metal detectors, but that was a formality, just like at the airports. I heard of inner city schools with metal detectors, but we didn’t have that in 1988 at my suburban high school. It was a distant fact, one which didn’t connect to my reality.

When I moved to DC, I lived at 11th and K Streets, Northwest. It was a border area, halfway between the low income neighborhood of Shaw and the office buildings of downtown. It was dodgy, with prostitutes of all sorts at night, but relatively safe. I could look out the bathroom window and see the dome of the Capitol. The White House was a fifteen minute walk away. As were FBI headquarters, Ford’s Theater, and the Federal Triangle.

I don’t remember what movie I was attending when the following trailer appeared in 1996.

But I do remember my shock at the image of the White House being obliterated. I remember the crowd cheering immediately thereafter. (Perhaps this was a reaction to the government shutdown the previous winter.) I guess my imagination could picture the reality of such an event, and the resulting collateral damage.

Every generation has an event which ends their collective innocence. The death of President Roosevelt. The assassination of John F. Kennedy. The Challenger explosion. Oklahoma City. September 11th. These are national events which connect us, which allow us to compare and share, to unite strangers. “Where were you when…?” Too little we celebrate national victories, like November 4th, or July 20th, or September 17th.

That loss of innocence tarnishes our ability to suspend our disbelief over fiction. Sometimes we are reminded directly of a loss or tragedy. Sometimes a movie accesses those experiences obliquely, drawing us further into the created reality before us. Sometimes fiction tries to react to reality, and fails.

(And then there was “Silent War“, where the United States refuses to return a religious artifact (the Terrigan crystals) to Attilan, which then forces the Inhumans to attack the United States. This ends with the United States sending mutated soldiers to the Moon, ending with the city of Attilan being destroyed by a mutated Marine. No international condemnation? No parallels to Mecca?)

(Or how about “Secret Invasion”, with the Skrull prophecy and religious extremism? What about the effect on normal people? Any world leaders acting as Skrulls? Any subversion, like that seen in DC’s “Legends” storyline, where the aliens try to sway public opinion?)

I admit, during storm preparations, I wondered how Hurricane Sandy could have been handled by superheroes. Maybe Storm could change pressure systems to change the hurricane’s path. Or Superman could freeze the precipitation of the hurricane while creating a counter-vortex around the eye, changing the climatological dynamics. But then I wondered, what’s to keep a super villain from doing the opposite, either overtly or covertly? Flap a few butterfly wings and a pressure system causes a hurricane to hit a political convention instead of veering off towards Alabama; or a storm to double in expected intensity, overwhelming expectations and emergency evacuations, making various administrations look ill-prepared. Of course, for every problem superheroes solve, another problem is caused.

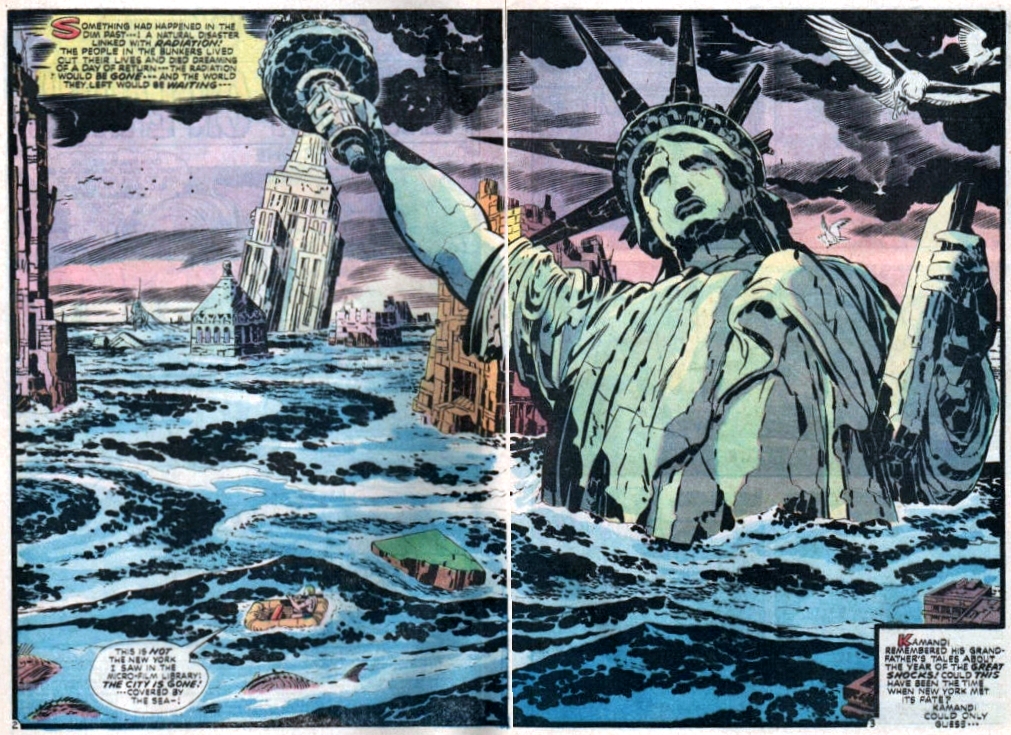

Perhaps we escape deeper, into fantasy and horror, experiencing that which is unlikely to happen, whether it is walking into Mordor or the Walking Dead. Or we avoid and escape reality via comedy, romance, and musicals, fueling hopes instead of fears. (Many dream of that “meet cute” moment which will land them in the Sunday Times.) Maybe we use those fantasies to better prepare against future calamities (and possibilities). Cautionary tales are quite common in childhood, as the world is full of metaphorical wolves, wicked witches, and things one should not touch, and it is better to learn from fiction than from Real Life.

In one respect, the Marvel Universe is just like real life. After the latest rumble has reduced the city to rubble, the local citizenry has to brush itself off and rebuild. That’s when the real heroes appear.

Good article, I enjoyed reading it. I think you’re asking too much for these stories to allude explicitly to real-world events. I would say comics started as escapist versions of real life (ie, Captain America punching Hitler), and the major companies haven’t deviated from that so much. It’s OK for me that they don’t address the aftermath from a huge battle in Times Square, because, comics. The closest to realism that Marvel usually gets is the Damage Control team, the team that cleans up after superhero battles. I think that Amazing Spider-Man #36 was an earnest tribute to the real heroes of a real thing. After all, Marvel started in NYC, is based in NYC and the artist is NYC-born and raised (the writer works out of Cali I believe). If you take that issue by itself, it works as a tribute.

I think that’s the problem with having a universe that has so many characters in one city. I also think there’s a problem with each mega event crossover that basically equals more and more destruction. Fear Itself made me realize that I was basically done with company wide crossovers because there had to be so many casualties that the number of super powered characters would eventually outnumber the normal citizen.

In this regard I think that this is the context when you realize why Wachtmen is a relevant read, since superheroes can hardly stop the natural course of human tendency to self destruction; or Paul Dini and Alex Ross´excellent exploration of Superman in Peace on Earth.

Robert Vass liked this on Facebook.

Comments are closed.