Last week I began my in-depth look at the history of Zenith and its attached legal dispute. As before I shall add my disclaimer: that this in no way speculates on who is right and who is wrong, and that it seeks only to bring you the facts, histories and quotes at my disposal – focusing primarily on what information is already in the public domain – in order to better allow all readers to form their own opinions and judgments.

Two years later the stirrings of the first contracts emerged (in late 1989) which introduced actual royalties, and a statement that the publisher was not looking to hand back copyright to anybody. And I chatted with previous 2000 AD editor Steve MacManus, and 2000 AD creator Pat Mills, about the situation prior to contracts: that creators were required to sign the back of their cheques in order to cash them. A docket was later added detailing rights purchased.

The position of Rebellion, the current owners of 2000 AD, is that this constitutes a contract. The position of Morrison, and various other creators, is that it does not.

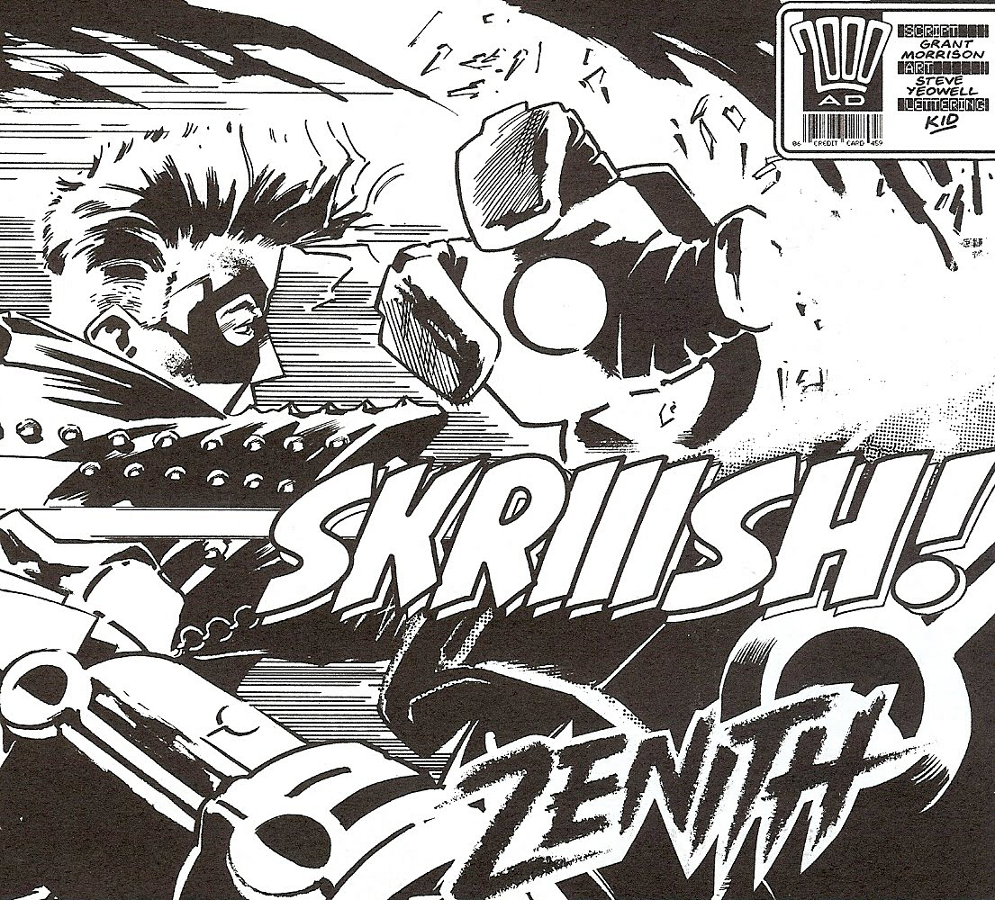

Unfortunately Steve Yeowell has decided not to comment after all, feeling that his replies would be too similar to those he has already given to The Beat, which you can read here.

The Origins of Zenith

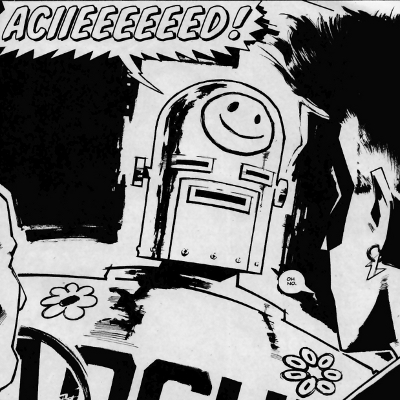

Part one finished in 1989. Before I continue, lets first dash back briefly to that earlier history of Zenith. As I said last week, Zenith had been re-shaped from an earlier, darker idea of Morrison’s for a David Lloyd project that didn’t come to pass – that project was Fantastic Adventure in 1985, a fortnightly boys comic proposed to IPC as a rival for 2000 AD. The Deep Space Transmissions website run by Ben Hansom reports that Morrison was assigned three strips:

“Johnny O’Hara (loosely based on Indiana Jones) with art by Modesty Blaise and Look-In alumnus John Burns; Nightwalkers (based on Ghostbusters) with art by occasional 2000 A.D. artist Ron Tiner, probably better known today for his art textbooks; and The California Crew, a sci-fi take on The A-Team with art by Steve Yeowell.”

And that Morrison also created a fourth strip, which you may find sounds familiar:

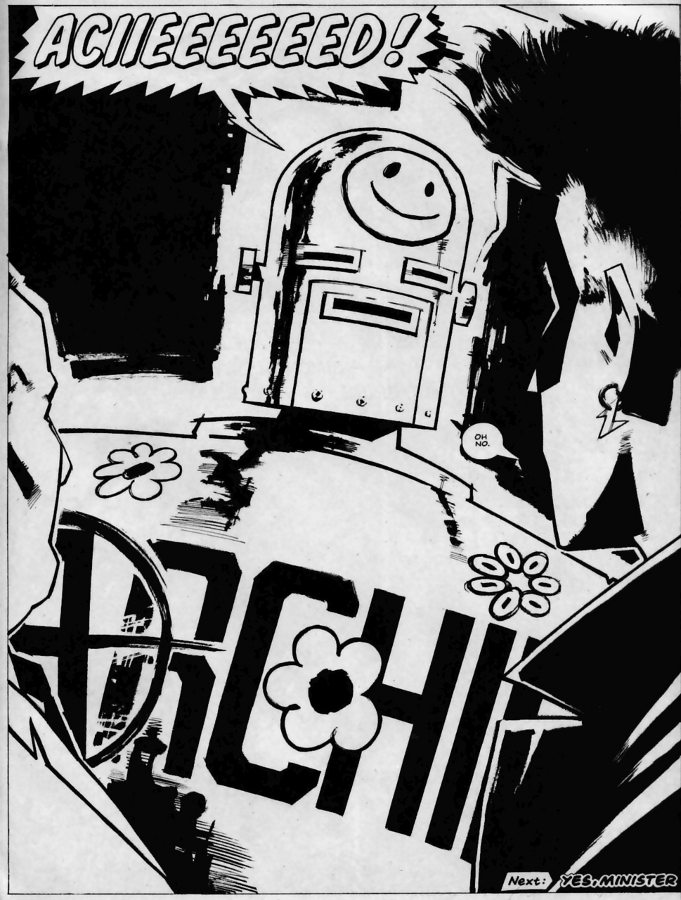

“A fourth strip, a super-hero epic created by Morrison and titled Zenith, was also earmarked for inclusion, though in a significantly different form than how it eventually appeared in 2000 A.D.. As conceived for Fantastic Adventure, Zenith’s tone was much closer to Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen; and the parallel-earth superheroic lineage angle, explored in depth in Phase III, seems to have been much more to the forefront. Morrison was keen to tie stylistic elements of comic-book history to their respective eras in the story, so for the elements set in the 1940’s, the characters were modeled on Siegel and Shuster’s Superman, for the 1960’s Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s early Marvel Comics, and for the 1980’s the prevalent Alan Moore-esque grim and gritty ‘realism’.”

Morrison himself said as much in an interview in Speakeasy #76 (1987):

“I’d come up with the basic storyline two years ago, when David Lloyd was putting together a boys’ weekly comic called FANTASTIC ADVENTURE. That didn’t get off the ground but I had come up with an idea for a superhero strip. I wanted to do something that paralleled superhero history, so we had characters in the ’40s who were very like the early Superman. We had the Maximan character, who was very primitive, we had the ’60s characters who were very Marvel pop arty, then we brought it up to date with the realistic ’80s characters. When it was revived after two years, because WATCHMEN and DARK KNIGHT had made such a big impact, we obviously wanted to avoid being compared with them. So we very definitely decided that we’d go for a lighter touch and get away from the tormented, demonic superhero. I think it’s been done by two very good writers, but I think in lesser hands it’s going to become really tedious.”

The history of Zenith then is moved back even earlier with Grant Morrison, before being re-shaped for 2000 AD and publication. In the comments of last weeks article, Hansom added more to the story:

“Tony O’Donnell (one of Grant’s colleagues at Near Myths and later collaborator on some issues of Starblazer) told me that Grant discussed publishing an early version of Zenith with John McShane of Glasgow’s AKA Comics & Books back in the early 80′s. Obviously it didn’t come to anything but it raises the possibility that the idea for Zenith stretches back even further than the David Lloyd/Fantastic Adventure pitch (which would have been around 1985). Whatever happened it seems pretty likely that Morrison had a pretty good idea of what Zenith was all about before Fleetway came anywhere near it.”

It’s not terribly surprising that Zenith has an older history than many realise given Morrison’s habit of filling notebooks with ideas that sometimes crop up in future works, but it’s interesting nonetheless to see further into the origins of Zenith.

Back now to where we left last week, after the events of 1989 when royalties were introduced, and the issue of copyright going to the creators was taken off the table…

Enter a Precedent

The wariness of giving back copyright is understandable from a business point of view – much of the success of 2000 AD was down to the creators alone, and to Pat Mills, John Wagner and Alan Grant in particular. Were the rights of, say Zenith, to be handed back, surely Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog and Robo-Hunter would be next.

Many would say that it’s the least that John Wagner and his fellow creators deserve, but could the publisher survive that outcome? It’s the same argument used time and time again within the comics industry, from Siegel and Shuster onwards. Except that at many other publishers the creators did indeed sign (often exploitative) contracts.

Robinson’s 2000 AD series – Medivac 318, Zippy Couriers and Chronos Carnival – contained characters that she had previously created, and she enquired what would happen if she continued to use those characters outside of the publisher, in text stories for example. She was told that Fleetway would sue her.

Let’s be clear here. Robinson was told that if she used her own characters, which were created outside of 2000 AD and previously published elsewhere, Fleetway would sue her. It’s a contradiction that will perhaps stand out later.

The Comic Creators Guild took up Robinson’s case, and brought in a copyright lawyer who informed her that there were only two ways she could have given up her rights: by giving them away or by selling them. In either case, a contract is required to show the proof of the transfer of rights. That contract did not exist.

The writer made the case that she had never signed a document assigning her copyright to Fleetway and that she had only given a license to Fleetway to publish her work. The publisher acknowledged that the copyright was Robinson’s, but not without cost.

Talking to Bishop in Thrill-Power Overload, Robinson says:

“For me it was a matter of principle and I had no choice… I expected other writers to take advantage of the opening I had made and claim their own copyright but I never heard if anyone did. I asked for and was given confirmation that I owned Medivac 318, Zippy Couriers and the Chronos Carnival. After that I was never invited to submit a script again and those I did submit were refused. I had been warned that if I insisted on fighting for my copyright I’d never get work from them again, but I could afford to make a stand. I fully understand that other people couldn’t.”

(When Robinson says she could afford to make a stand, I do not believe she is talking financially – as she had sought out the Comic Creators Guild to help her – but I am told that she had apparently heard from friends in 2000 AD that she was not likely to be getting more work from the publisher.)

I’m told by other 2000 AD sources that it was more a case of those strips not being a “big deal” and that they did not want the fuss and expense of a High Court case. The publisher maintains that Robinson’s case was not a precedent as they voluntarily accepted that Robinson owned the copyright to her series.

I asked David Bishop – author of Thrill-Power Overload and former 2000 AD editor – for some clarification on this point, and to the best of his memory he recalls:

“The official line at the time was the rights were being voluntarily returned to Hilary, and as a result there was no legal admissions or precedent being established. Who owned what was certainly never put to any legal test in that case, at least not to the best of my knowledge.”

Medivac 318 did indeed appear first in a short story published by Robinson in the 1980s, while Zippy Couriers was originally published in a Belfast fanzine in the same time period.

The story of Chronos Carnival seems more muddy however, as although this too had originally been written as a short story I can find no record of it actually being published anywhere. Much like Morrison’s early origins of Zenith perhaps…

Robinson is now retired but does a great deal of painting. In a comment in one group dedicated to writing on an art site, she says:

“I am retired now but in my time I was, albeit briefly, a freelance writer for a British Science Fiction comic called 2000AD. I had a slight disagreement with them over my copyright, and even though I won the case, I haven’t written much since. Instead I’ve discovered an artistic talent that I didn’t know I had…”

For those that wonder why more people don’t push for copyright in comics, this would appear to be the – quite depressing – answer. Robinson did get the publisher to accept that she owned the rights, but it did not go to court. That was avoided, as it could have created a precedent for other creators to use. This is a classic situation that is repeated throughout the years in the comics industry – when publishers feel they are losing, they will avoid court at all costs to avoid legal precedents being set down. Settlements out of court leave new potential cases floundering.

Precedent or not, it does seem possible that 2000 AD voluntarily gave up the rights to Chronos Carnival which it otherwise would have owned outright.

Crisis Point

In 1988, Fleetway Publications had also launched a new fortnightly anthology comic called Crisis, aimed at a more mature audience. While Steve MacManus, the previous editor of 2000 AD who had been championing for contracts for years, was now managing editor of the 2000 AD group, Crisis and the Megazine were the titles he had direct control over.

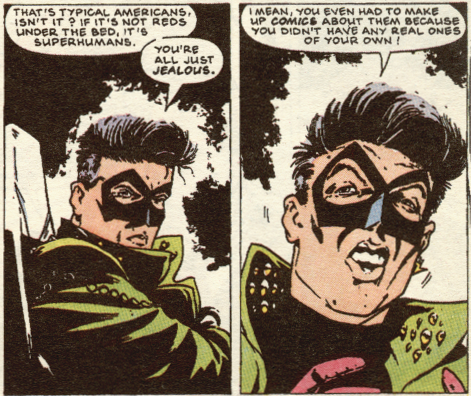

In ’89, Morrison and Yeowell had teamed up for another comic title, this time for Cut, a Scottish arts and music magazine. It caused a bit of controversy to say the least! The New Adventures of Hitler was a satirical take on what Hitler had got up to between 1912-13, based on a book (The Memoirs of Bridget Hitler) by Hitler’s sister-in-law claiming that he had stayed with her and her husband in Liverpool.

Hitting the headlines of The Sun and seeing Morrison labeled a Nazi by co-editor and 80s Scottish soft-pop star Pat Kane, Cut folded before the story was complete after just two 4-page instalments. Of course the comic in no way promotes fascism, showing a Hitler that is completely batshit insane and dangerous, but comics are as ever the target of would-be censors.

And so in 1990, it began being published, coloured and in full, in Crisis. Speakeasy 107 in March 1990 reports that:

“When asked whether the 2000 A.D. Group held the rights to collect the series in one volume after its initial Crisis run, editor McManus replied: “Well, we’ve got the option to bid for it. We’ve paid for the rights for one use only.”

At one point Morrison had vague plans of setting up his own self-publishing imprint – Snobbery with Violence – to publish collected editions of The New Adventures of Hitler as well as Bible John and the never realised Doctor Mirablis, but the imprint didn’t quite make it. (Fans of Alan Moore are perhaps reminded of Moore’s own rather costly Mad Love publishing company.) As Morrison says in an interview with Jonathan Ellis at PopImage: “Nothing ever came of it, rather like Communism.”

Speakeasy #109 in May 1990 featured an interview by Nigel Curson with Morrison and Rian Hughes about their reinvention, Dare, for Revolver magazine. Revolver was a monthly sister publication to 2000 AD, and was aimed at a slightly older audience. With editor Peter Hogan at the helm, contracts for royalties and re-use scenarios were the norm, just like at Crisis.

Dare was a revisionist take on the classic Dan Dare, an intelligent attack on the ideologies at play. The creator of the original Dan Dare strip, Frank Hampson was another in the long line of creator casualties, losing his rights to his creations and treated shamefully. Dare was, in part, also about that.

In the interview Morrison says:

“Basically, this strip is about what happened to Frank Hampson. The theme of it is the same thing, and it’s that kind of Faustian theme of selling your soul for something that’s essentially wicked. Frank Hampson did the same thing, and was pretty much destroyed.”

Asked by Curson whether he saw himself in the same situation, Morrison, still in his Morrissey persona years, replied:

“Well, I have been within something like Zenith, where I don’t own anything at all. I’m sure I could make money on T-shirts and badges and all kinds of stuff but I don’t really want to. I did that because I didn’t have any work at the time. My position on that is if you sign the contract, you read the small print and you know what you’re getting yourself into, so it’s your problem.”

Of course it later emerged that in the case of Zenith there was perhaps no contract at all. Morrison would have signed the back of his cheques, or possibly the docket slips, but contracts at 2000 AD did not exist at the time of Zenith’s publication.

Incidentally, for those wondering about who owned Dan Dare – the character was indeed still owned by Fleetway Publications at this time, so available for 2000 AD to use. When Egmont bought the company in the early 90s, the character was later old on separately.

The Dan Dare Corporation, which gave Rian Hughes permission to reprint Dare in his brilliant collection, Yesterday’s Tomorrows, is the current owner of Dan Dare. Dare remains copyright to Grant Morrison and Rian Hughes, as does another strip included in Yesterday’s Tomorrows: Really and Truly, from 1993’s Summer Offensive event in 2000 AD.

Here Comes Marky Mark

1991 saw half of Fleetway bought by Gutenberghus Press (now known as Egmont) and after the death of Maxwell in 1992, GP bought the remaining half and merged it with their existing London Editions to form Fleetway Editions. The same year saw the return of Zenith for his final Phase IV, after Morrison had achieved success in the US with Animal Man (1988-90), Arkham Asylum (1989), and Doom Patrol (1989-1993).

The following year saw 2000 AD’s infamous Summer Offensive of 1993, when the terrible trio of Morrison, Mark Millar and John Smith were given free reign for eight blistering weeks of violent mayhem. Strips included the aforementioned Really & Truly by Morrison and Rian Hughes; Slaughterbowl by John Smith and Paul Peart; Maniac 5 by Millar and Steve Yeowell, Richard Elson and David Hine; the Judge Dredd story Inferno by Morrison and Carlos Ezquerra; and Big Dave by Morrison, Millar and Steve Parkhouse.

Millar and Chris Weston created the first series in 1993, but Millar had stopped working for Fleetway by the time a second series came around in 1995 and objected to another writer taking over the strip. Thrill-Power Overload tells that Millar launched legal proceedings over both Canon Fodder and separate grievances regarding pay, and the case was settled. Plans to continue the series further were shelved.

Michael Molcher, PR Coordinator for Rebellion, tells me that there is no record of Millar being paid off over the matter. I turned to David Bishop again for some extra information, and he told me that there may have been some sabre-rattling, but the upshot had been that there were contracts for everything Millar had done on 2000 AD and the Megazine and that all belonged to the publishers – with the exception of Big Dave, copyrighted to Morrison, Millar and Steve Parkhouse.

Big Dave is another strip that seems to have some controversy over who was supposed to own it, but the rights ended up remaining with the creators. In many ways this is perhaps another example of a strip that the publisher didn’t think was a big enough deal to quibble over – the character was divisive and very much of his time, though in recent years has enjoyed a growing cult status. It all sounds a little familiar…

Thrill-Power Overload notes that around the same time, new contracts were offered to creators that covered audio/visual rights. However, these contracts are said to have offered worse terms than before.

In 1996, Fleetway Editions was renamed as Egmont Fleetway. Thrill-Power Overload states that in 1997 a long-running dispute between Egmont Fleetway and IPC was settled with Egmont Fleetway receiving £25,000 worth of free advertising in IPC publications (yes, those infamous “women just don’t get it” ads that ran in the porntastic lads mag Loaded of all places).

Summer Magic

1995 also saw the end of a rather unusual strip called The Journal of Luke Kirby. Written by Alan McKenzie, it had been running since 1988, telling the rural story of a young boy learning his family’s supernatural secrets. It’s great and pretty stuff. The strip has never been collected. Why? Because Alan McKenzie states that since he never signed over his copyright, the strip belongs to him. If this sounds familiar then you’d be bang on of course – this seems to the same situation as with Zenith.

McKenzie was earlier an assistant editor at 2000 AD in 1987, but this was before contracts were introduced at the end of 1989. He later became an editor again in 1994, and is very sure of his rights in this case. Writing on his own website he states:

“The first episode appeared in Prog 571, 23rd April 1988. Which means the series predated both “Harry Potter” and the tv show The Wonder Years, which I always thought the Luke Kirby series quite resembled.

What I liked about Luke Kirby is that it’s a story about children for grown-ups and, of course, as I never signed an Assignment of Copyright contract with Fleetway/Egmont, the character format belongs to me.

I had always planned that Luke would grow up in real time as his story unfolded, but after a dispute with the publishers about my owning the copyright, the character went into limbo. Still copyright law is on my side, so who knows ..?”

Correcting an article written about him in 2007 where the author states that the copyright was signed over when the paychecks were cashed, McKenzie says:

“The copyright did not get signed over – as you state – when the cheque was cashed. That is not possible under European law. Copyright is only ever reassigned when the creator (that’s me) signs away his rights in a legally binding contract (which I didn’t).”

The original artist that worked on The Journal of Luke Kirby with McKenzie, was the magnificent John Ridgway. In an interview with David Robertson for The Comics Journal in 2011, Ridgway confirmed that rights were never signed over at the time, but revealed that he had later signed away his rights due to the format of the contracts at Rebellion.

“I finally received work from Alan Barnes when he took over. By that time Rebellion owned 2000 AD and issued a contract for every job. An addendum of each contract was a list of all the work done by that person on work owned by that company — which included Luke Kirby. I doubt that [R]ebellion ever knew that I hadn’t signed away Kirby, and it no longer seemed worthwhile making a fuss.”

In the same interview (which is fascinating, I highly recommend reading it in full), Ridgway also states that he never received any contracts (or deadlines) for his work on The Journal of Luke Kirby.

“However, contracts started to be issued on work for 2000 AD to make it compatible with the terms offered by Marvel and DC in the States, who were offering more-regular work with royalties and reprint fees. I should have received contracts for my work, but never did (I didn’t receive any deadlines either — things seemed a bit sloppy in the editorial department).”

This is particularly worth noting, as Ridgway’s work on the strip continued until 1995. Well after the introduction of contracts in late 1989, which illustrates that even after contracts were available at 2000 AD, they were not always used.

The Journal of Luke Kirby, as popular and incredibly influential as it was, has never been reprinted in a collected edition.

To Be Continued

I originally planned for this to be a two part series but in light of all the extra help I’ve received, the above had another >3k words to go!

So in Part 3 next week, I’ll be looking at just how UK copyright law works both now and at the time of Zenith’s original publication; another important case of a writer getting their rights back; what the contracts at Fleetway looked like when they were introduced; and where we currently stand with the fate of Zenith. Not to mention the story of Robot Archie and his IPC pals, and a guide to what publishing company was called what, when.

In fact, next week I think we might just see the proverbial hit the fan…

With special thanks to:

David Bishop

Ben Hansom

Pádraig Ó Méalóid

Mike Molcher

David Mosley

2000 AD Alumni

Laura Sneddon is a comics journalist and academic, writing for the mainstream UK press with a particular focus on women and feminism in comics. Currently working on a PhD, do not offend her chair leg of truth; it is wise and terrible. Her writing is indexed at comicbookgrrrl.com and procrastinated upon via @thalestral on Twitter.

Paul de saveray owned the Dan date copyright at the time Dare was published. Fleetway may have had the license but they did not own the copyright

Dare was published stating that the copyright of Dan Dare belonged to Fleetway (see the Xpresso collected edition from 1991 too). Paul de Saveray did have the film rights to Dan Dare however, though I believe he did try and buy an earlier version of Dan Dare in comic form in the early days of 2000 AD but that’s another story…

I feel quite defensive towards Hilary Robinson, whose work has tended to be portrayed as one of 2000AD’s nadirs, for the most part unfairly. I’m not sure that she would have been employed much beyond 1990 even if she hadn’t kicked up a fuss over the rights, even while dreadful hacks like Michael Fleisher and Mark Millar seemed to have a free pass to take over the magazine. (Millar’s complaints over ‘Canon Fodder’ – and I think also ‘The Grudge-Father’ – are a bit rich given what he did to some of Tooth’s most beloved characters elsewhere.)

But I think this article does clarify the technical issue of whether Robinson’s case set a precedent for Zenith. On the other hand, and unless Rebellion can turn up some kind of paperwork to the contrary, I think Morrison’s (and Yeowell’s) rights to Zenith are fairly unambiguous. I’d prefer to see this settled amicably, but I feel that Morrison has both the grounds and the justification to sue.

Hilary Robinson’s Chronos Carnival was a low point during a low time for 2000AD, but her other strips were better than many and certainly a cut above anything Fleischer wrote during that dark period.

One question that may not need addressing is the work of other artists on Zenith. the Mandala and Maximan interludes drawn by Jim McCarthy and Mark Farmer (maybe?). While absolutely inessential, I’m wondering if they’ll be included in the trade for completeness’ sake.

huh, the pattern seems to be the publisher ferociously insists it has all the rights until a creator gets a lawyer involved.

Interesting, especially the bit about Fantastic Adventure.

I suppose the floodgates didnt open when Robinson got her stories back wasbecause that most creators needed to make a living. I have an old Steve Yeowell interview about Zenith here if anyone wants a look. https://www.facebook.com/HiberniaComics?ref=hl

“Hilary Robinson’s Chronos Carnival was a low point during a low time for 2000AD, but her other strips were better than many and certainly a cut above anything Fleischer wrote during that dark period.”

‘Chronos Carnival’ is very dull but its no worse than contemporary strips like ‘Dry Run’ or Fleisher’s interminable ‘Harlem Heroes’. The problem was they were all running at the same time – along with the final third of ‘The Horned God’, which was obviously a landmark in British comics but by this stage was being dragged out far beyond its natural lifespan (a condition now officially known as Pat Mills’ Disease).

Robinson wrote a third Chronos Carnival series that was never published – which was quite unusual given that the policy at the time was that anything paid for had to be used. (I gather at one point the plan was that John Smith would rewrite it in his own particular… ah… idiom.) But that seems to have been fairly soon after Robinson’s final strip. If Robinson’s complaint was handled by Rebellion that would have been much further down the line. If Fleetway buried a strip in contravention of their publishing policy, it suggests that no one would have been particularly unhappy to let Robinson have it back.

This is somewhat related and something I’ve been meaning to ask for the last few months.

Is it safe to assume that the Beat is paying you an equitable rate for posting your writing, and allowing you to own what you write?

A comment in a longer conversation between Heidi and Spuegeon a while back got me thinking…

David Mc – Thanks for the link! Terrific stuff.

Kate Halprin – with Robinson it was also around the time where a lot of things were changing, and to be honest it looks like things were pretty disorganised at the best of times (Ridgway commenting on never receiving contracts or deadlines as late as 1995 for example). I think her work is given a lot more flack than it deserves… I wonder if it’s partly fans resenting her stance on her copyright? Not sure.

jaco lyon goddard – I cannot speak for other contributors as everyone’s role is slightly different here, but I am not paid for my work on the Beat. For numerous reasons that’s a situation I’m quite content with – mostly because the bulk of my other writing elsewhere is paid for, the Beat is a terrific platform for my less mainstream-friendly work, and because it’s a website that I am terribly fond of.

And yes, I retain the rights to all that I write here. Incidentally, this is also the case for much of my newspaper work (I give them first publication rights only) but different from my magazine work (in which I sell all the rights).

Yes, I also write here for no reward bar the glory. The Beat is a shining example of what comics journalism on the Internet should be, but rarely is. I’m proud and happy to be a contributor, and couldn’t think of a better place to have my stuff on show. (I can’t help thinking I could have phrased that better…) And, like Laura, everything I post here belong to me, and why shouldn’t it?

Without going into the economics of The Beat too much, all contributors do own their content, but economically it’s more of a profit sharing situation.

I stand corrected. De savary misrepresented himself to me then! I didn’t see the paperwork.

Or maybe my memory is bad!

I think the reason Hilary Robinson’s stuff isn’t especially popular is that it’s rather less macho than fans were used to. The leads in Medivac 318 and Zippy Couriers were female and non-violent, and the male lead in Chronos Carnival was paraplegic, and didn’t get to kick much ass. Peter Hogan’s stuff got the same reaction for the same reason.

I certainly won’t claim to understand the economics of running a site like this, but not compensating the writing staff on a fairly well trafficked site that sells advertising space seems inconsistent with the “dont work for free” message that is often expressed here.

Again, I really have no idea what I’m talking about, but finding this out shocks me and makes me a little uneasy as a long time follower.

I have written before, and no doubt shall again, for sites that pay but The Beat is not my main writing gig, nor is it my job – I suspect that’s the same for most of the contributors. Just as the best journalistic writing is often done outside the pages of the mainstream press, so it is with comics journalism – lots of great articles in online fanzines, perhaps of a higher quality than those in more commercial sites.

I’ve also been open to other unpaid jobs in the past, if it’s something I’m passionate about and have the time, as one of my own aims with my writing is to reach as broad an audience as possible. The Beat fills that quite nicely for me!

Others may vary as I’ve said, but I seek payment based on what is possible for the publisher – newspapers have more money, magazines often slightly less, websites far less again, and in some cases there is no money to be had, but a certain reputation or other non-financial reward.

I also have experience with website running, on a small and larger scale, and the difference between financing the former and the latter is staggering. I just hope The Beat continues to survive and thrive to be honest.

You guys don’t get paid? lol

I remember Zippy Couriers very fondly, and was not aware of any of the copyright factors until now. It was one that I had been hoping would return again after it finished.

Chronos Carnival I vaguely remember as not being as good, but completely agree with the comment that it was affected by the never ending Horned God saga at the time.

My biggest memory of Chronos Carnival isn’t that the story was bad (though I don’t think it was good) but more than Ron Smith’s on it just didn’t work for me on any level.

Though I did like Zippy Couriers…

The whole rights issue has long blown my mind – it just seems so… ridiculous! John Freeman kindly outlined the basics to me on Facebook once, but even then, it feels like a particularly peculiar purgatory.

As a mere punter you feel conflicted: you want your favourite stories to continue in your favourite comics, preferably executed by your favourite creators, yet at the same time you want your favourite creators to be justly rewarded.

We want both never-ending adventures, but also narratively satisfying, well-structured stories that end when they should. And how are we rewarded? That Harlem Heroes strip that could not be killed, and Halo Jones adrift forever, unfulfilled.

I look forward to the next installment with eager anticipation.

PS Leo Baxendale’s earlier travails on this front might also be instructive; his autobiographical volume A Very Funny Business covered his own legal battles with DC Thomson.

PPS In the first part, shouldn’t it be ‘Kelvin’ rather than ‘Kevin’ Gosnell?

PPPS Another fan here of Medivac 318. For me it had the feel of some of the earlier serials like Meltdown Man, slightly out of kilter with the ‘core’ of 2000AD but enjoyable nonetheless.

I have fond memories of Medivac 318 and like to think that it would be better remembered if 2000AD hadn’t been stuck in the middle of a perfect storm of converging problems in the late 1980s/early 1990s. It’s the sort of emotionally-grounded and quietly interesting strip that contrasts nicely with all the pyrotechnics and grotesque satire going on elsewhere – and so would have looked better if everything else in Tooth had been at the top of its game.

BristleKRS – eep, cheers for the correction! I shall go fix that.

“As a mere punter you feel conflicted: you want your favourite stories to continue in your favourite comics, preferably executed by your favourite creators, yet at the same time you want your favourite creators to be justly rewarded.”

I think this is pretty much exactly the issue, and the result of that ever present tension within comics – the people who want to create, and the publishers who want to profit. The latter facilitates the former, but it can also strangle the life out of it…

Very good articles on Zenith, Laura.

As you weren’t around in the 80’s and privy to actually what was really going on back then with that small bunch of people who were blazing a trail in the British comics industry, let me add a few insights:

Back in the day, the only new thought on superheroes were from Alan Moore in his version of Marvelman. I didn’t particularly like the strip (finding it a continuation of the wordy, purple ‘Don McGregor’ school of writing) and wanted to make my own, new statement about the superhero concept. I invented Paradax! in the early 80s, and asked the question, ‘what would it be like if an ordinary guy down the road became a superhero?’, which over 30 years ago, was a fairly novel approach: He would drink, smoke pot, fuck girls, watch himself being interviewed on TV, be an annoying self-infatuated asshole obsessed with stardom, have a manager, and take the money and run. I designed Paradax with a big exaggerated Superman ‘S’ quiff for hair and based his look a bit on the 60’s Kid Flash. I then added street clothing as I figured that realistically, he would look like a dick wandering about in a skin tight yellow outfit. This was all light years from Alan Moore’s ‘grim n gritty’ take, and Paradax was the only other version of a superhero coming out of the UK at the time. (This is some years before Zenith.)

I fleshed out the storyline and took it to Peter Milligan to write the script. Pete knew almost nothing about superheroes, and that was appealing to me, as he had no reverence for the genre. Paradax! appeared in Strange Days 1 through 3 and was our only attempt at a superhero. In tone, it was throwaway, sexy, breezy, a bit like a catchy pop single disguising a big fuck-off statement (like the Sex Pistols’ singles)…

Strange Days was a bit ‘left-field’ from the straighter 2000AD world and soon the ‘groovier’ people in comics (like Grant Morrison) were gravitating over to our scene rather than the ‘Alan Moore school’ of comics seen at Warrior. Grant was besotted with our stuff, as it was a totally new and original manifesto for what comics could be and a vital part of the 80s British Invasion in the USA. We talked comics and movies and above all music at many a gathering.

Grant approached me to draw the Zenith strip he was pitching to 2000AD, and initially I was quite interested. I designed a bunch of characters from his pitch, but as I read the full scripts later on, I saw that he was lifting quite a lot from Paradax!. The other story elements in Zenith, apart from the Paradax-inspired ‘media superbrat’ stuff seemed like the usual comics fare – ‘super soldiers’ and all that magick/Dr Who stuff he was into. That bored me, as I’d heard it all before… I couldn’t see the upside of illustrating a strip that was essentially ripping off my own original thought, so I passed on drawing it. Let me stress, that Steve Yeowell drew it far better than I would have. His work was really good, and he was absolutely the right guy for the job.

When I see it written that Zenith was some sort of brand new take on superheroes, the ‘first of the celebrity superbrats’ etc, well, I do tend to spit out my cawfee… Even the ‘magickal’ stuff in Zenith wasn’t original (2000AD had to pay off some artist for having his stuff ripped off later on in the series).

I liked some of the later ones with Robot Archie, etc… When it got a bit more surreal, and more of it’s own thing. It was fun.

Zenith is a pretty good strip, but it is derivative of my own Paradax! material. There is a ‘greatest hits’ collection of my 80s work coming out in September, THE BEST OF MILLIGAN & McCARTHY, which includes the Paradax strips. You can have a look and make up your own mind. Note the dates, and that one strip preceded the other. One’s the original, one’s the version. I never produced much stuff in comics, I was a very slow artist – and eventually moved onto TV and film as I got bored with drawing these influential strips that were picked clean for ideas. My stuff never sold in huge amounts and I felt I said what I had to say in comics and wanted some new creative challenges. And to make some money.

Around that time Grant asked me to design stuff for ‘Kill Krull Krew’ (I think it was called) and Doom Patrol. I designed lots of the original designs for DP, and maybe a year later Grant bumped into me at a British comic convention and told me he was having trouble coming up with a good HQ for the team. We chatted and had a laugh and at some point, I suggested a transient transvestite street called ‘Danny The Street’, (which was based on The Beatles’ terraced houses in ‘Help!’ and Danny La Rue, a bizarre transvestite lounge-singer act seen on British TV in our younger days). Grant added the bunting and written notes in the windows etc and made it all work. He gave me a credit in the issue of Doom patrol that DTS debuted in. But curiously, Grant has subsequently claimed that he invented Danny The Street whilst walking backwards around Paris in a Situationist hash-trance… or something. And that’s annoying to me, as he can’t admit that what many consider to be the best idea in Doom Patrol wasn’t his…

You need to take what Grant says about Zenith and his earlier career with a pinch of salt. There’s a lot of revisionist legend-buffing going on…

Some of us were actually there.

Thanks Brendan – I’m both glad and relieved that you’ve liked them thus far! I was indeed but a sprog in the 80s, and it’s been interesting trying to match up what people said recently with what they’ve said in the past. Not least when you add in the passage of time, the put on personas at that time, and the general drug haze hanging over it all, heh.

After these three parts I’ll be moving on to the rather more fun job of reviewing Zenith, and Paradax definitely features large there – not least because it came first and was obviously a big influence on Zenith, but also because it seems bizarrely underrated… I don’t know why it isn’t sitting in the prime spot of UK superhero history really across from Moore’s uber dark approach. I was stoked when I found out about the Best Of collection from Dark Horse – particularly as it’ll actually get into the hands of readers old and new which is fantastic. (I think it has Skin too?)

You’re quite right about the history revisionism, which seems to be happening all round – some of it accidental I’m sure, on both sides, but it does make things tricky. I’ve tried to stick with the facts and the quotes, as there is also a whole heap of other information outside of the public eye as well. It’s been fun digging through some comics history but ultimately also a bit depressing to be honest. It feels like an industry where creativity is seldom rewarded as it should be, and many of the best end up leaving or going unheard of :/

Thanks for clearing some stuff up! Much appreciated.

Man I loved Strange Days. Thanks for writing, Brendan.

“Having previously sold text stories to other publishers, Robinson had assumed that comics worked the same – that the author retains the copyright.”

I find this very difficult to get my head around. She was a professional writer – she did not think to check this before hand? I have never written anything without first finding out who would end up owning the work…

Richmond A Clements – with no disrespect intended to Robinson, I wouldn’t exactly call her a professional writer really. Her previous short stories had been sold to zines in Ireland, including the short-running Ximox anthology… I’m not sure that writing was ever her main income or even a significant one.

We’re looking at someone who wrote a few things for some zines and then moved to comics for the first time – I wouldn’t expect them to be an expert in checking things, particularly with a lack of contracts. Her experience at 2000 AD seems to have ended her writing career nonetheless, which is a shame as her work does have its fans and was quite promising in many ways. (And she remains one of the very few women to work at 2000 AD over their history too of course.)

One interesting aspect to the rights issue that seems to go unmentioned regarding Zenith is precisely who owns the rights to the old IPC characters used within, especially Robot Archie. I believe that they weren’t part of the deal when Rebellion brought the rights to the 2000ad stable of characters, and wonder if they’ve had to be have their rights licensed in the new collection. (Those rights may be a reason Morrison has never taken the Zenith work elsewhere). The IPC characters were last seen being published by DC in the mid noughties.

Hilary Robinson was treated dreadfully by 2000ad, but it has to be said that comics fans at the time weren’t entirely blameless: I attended a couple of UK Comic Art Conventions in London in 1988 and 89, where she was a guest at one of them (I can’t remember which) and she was the only guest I’d ever seen booed at a convention. If I recall correctly she was the only female guest that year. I thought it a disgusting spectacle,

I discovered Paradax via the Vortex reprints in the late 80’s, and they were wonderful. I’d like to say they were a big influence on me, but I am no-where near as good an artist as Brendan McCarthy, and can at best be said to be an admirer. And Laura is right, it’s quite frankly bizarre that Paradax is so unappreciated, but I wonder if that isn’t a product of it’s time, as reflected in attitudes to Hilary Robinson: the definition of adult is limited to grim and gritty, while whimsy is dismissed as embarrassing.

Strange Days was one of the best things to come out of comics in the 80’s and despite his brief career, Paradax is still one of my favorite takes on superheroes. It’s a shame that Milligan & McCarthy didn’t have more to say with the character, but I respect that they didn’t want to wear out the concept.

I also thought it was very cool that the character’s look was very much influenced by the original Kid Flash. If only Wally West had been an anti-authoritarian apathetic punk rocker instead a Ronald Reagan-worshiping Young Republican! That would been a Teen Titans worth reading (don’t get me wrong – Wolfman & Perez’s Titans was very enjoyable – but when it comes down to it, it was a superior soap opera like the early Marvel comics it took inspiration from).

I remember Zenith, but I’d completely forgotten about Paradax. Weird how great stuff falls by the wayside and into the memory hole. I remember my guy buying the Paradax comic, with two other stories in it: Two old gay gents in a bed floating in the ocean and another Oscar Wilde type magician lounging about. I think I liked them better than Paradax, as I recall. The comics Brendan McCarthy did with Peter Milligan always had a strong smutty undercurrent, they always made me laugh with the sexual innuendoes. Comics in the UK were generally sex-free and very serious, so I have to say, I enjoyed the filthy minds of those two creators! I think Pete Milligan later went onto do a ‘kinky’ thriller with Vertigo.

Ah, those were the days… More smut please!

Carey – Archie does indeed take centre stage in tomorrow’s final instalment :) That story about Robinson at the con is just awful. Good grief, no wonder she didn’t seem to care about the prospect of losing further work there.

It is interesting that many of the “forgotten” comics that were often quite inspirational for other, later creators are in that same period, pre-Watchmen and co. Perhaps they were just that tiny bit too far ahead of their time?

tricia – I quite agree on the call for more smut!

In response to Brendan:

“Zenith” might be eponymous but the title character actually has remarkably little agency in the strip – it’s a big generational saga (by design) and the central mover is a Tory MP who looks like Michael Hesiltine and has a druggy 60s hippy past. You’ve also got a bunch of alien uber-gods (a nice take on the usual Lovecraft mythology), a DC Thompson Crisis On Infinite Earths and a ton of contrasting superheroes from the 1940s to the 1980s.

So if Paradax begat Zenith – and I haven’t read Paradax, mind, but I’m chomping at the bit – it’s in the same way the book pulls in super hero tropes from a massively disparate range of perspectives, eras and takes. While this might be a little bit naive on my part, my assumption would be that young Morrison assumed Brendan McCarthy was the 1980s future of superheroes (I wish!!!) and this was a kind of fan fiction approach (I had the chance to ask Morrison about Zenith once but my arse went – a missed opportunity).

So yeah, Zenith 1) uses pastiche as a narrative device across a huge, huge story and 2) Zenith isn’t the hero in it, and actually does remarkably little while a Conservative frontbencher schemes and schemes. I can see why Brendan wouldn’t really like the take on things: if Paradax is a punk take, Zenith is an indie take by way of the Smiths until book 4, when it sort of becomes Top Of The Pops With Murder.

Anyone missing this is sort of missing one of the funniest points of Zenith. He’s a patsy.

Also Brendan, big fan, I think you’re an utter legend and I cherished your issue of Solo.

Speaking of under appreciated work by British creators – and vaguely relevant to the matter at hand – I’ve always been mystified that Peter Milligan’s SKREEMER from 1989 isn’t a name on everyone’s lips. Nice to see the lovely Rich directing all that traffic over from the Benighted Competition, by the way!

“I find this very difficult to get my head around. She was a professional writer – she did not think to check this before hand? I have never written anything without first finding out who would end up owning the work…”

I’m a writer whose had a small amount of professional freelance non-comics work published in the past 20 years, and I have to say that the freelance assumption (backed up by copyright law) is that the work is yours unless you sign something that says otherwise. Which is of course why these articles exist.

The thing is, I know (and deplore) how the comics publishing world works but it is an exception rather than general practice but I’m not sure how widely this would be known 25 years ago, especially someone coming to the field fresh. Fleetway’s practices were not something she should have been obliged to look up, it’s something that should have been obvious to her when she was presented with her contract.

But she wasn’t given a contract, she never signed over the rights, and her stance is the correct one under the terms of English law.

@ Carey – “One interesting aspect to the rights issue that seems to go unmentioned regarding Zenith is precisely who owns the rights to the old IPC characters used within, especially Robot Archie. I believe that they weren’t part of the deal when Rebellion brought the rights to the 2000ad stable of characters, and wonder if they’ve had to be have their rights licensed in the new collection.”

I’m not sure that Fleetway had the rights to them in the first place. In 1992, they published a one-off ‘2000AD Action Special’ featuring re-imagined versions of, among other, the Steel Claw, the Spider, Cursitor Doom and Mytek the Mighty. They also included Kelly’s Eye, whose lead character had recently appeared in the 2000AD series Universal Soldier and would go on to have his own run in the weekly in 1993.

Unfortunately IPC still owned all these characters, but this only came to light after the 1993 run of Kelly’s Eye. When Fleetway had bought the IPC comics titles they only bought the rights to strips that had run in then-current titles (including not just Tooth but also Roy of the Rovers, the relaunched Eagle, and a few others).

So when Zenith Phase III was published post the Fleetway takeover, it was full of characters that no one knew they didn’t own. Though curiously I find it’s the ‘DC Thomson characters with the serial numbers filed off’ that linger in the mind from that story.

Comments are closed.