[Previous chapters: 1 to 8 – 1953 – 1985 Roundup, 9 – The Dawn of Eclipse, 10 – Alan Moore at Eclipse, 11 – The Twilight of Eclipse, 12 – All About Angela, 13 – More Angela, More Courtrooms, and Much More Todd, 14 – Back to Marvelman, 14.1 – Updates and Clarifications on Marvelman]

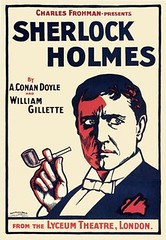

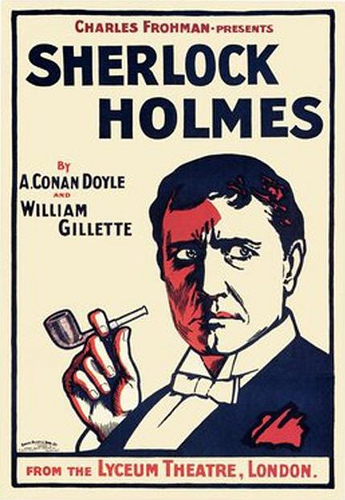

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.

I should also point out that any opinion I put forward is simply that: my opinion. An opinion based on several years’ worth of speculation and research, and perhaps some pieces of information that have not previously been seen publicly, but none the less only my own opinion of what I think those facts mean. I’m also well aware that there are a lot of things I don’t know, important pieces of information I know exist but that I haven’t been able to get a look at. If fact, my situation was described perfectly by one of the last great American philosophers, Donald Rumsfeld, when he said,

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.

I know, for instance, that there is alleged to be a drawing of Marvelman, or a character similar to Marvelman, that apparently dates from before the generally accepted creation of Marvelman, signed by Mick Anglo, which is supposed to be part of the proof that Marvelman was copyrighted to Mick Anglo Ltd, but I haven’t seen this drawing, and my knowledge of it is purely anecdotal, so it’s difficult for me to make any decision based on it. (There are other cases of artwork being used to prove that a character had been created before its publication by a comic company, like the case of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby creating Captain America, which was subsequently published by Marvel Comics, but there are also cases where claims have been made about artwork that proved to be false, such as the case of Will Eisner and Wonder Man.)

So, having hopefully covered my ass legally, here goes.

Different people claim to own different amounts of different things, but there is virtually no paperwork to definitively prove their claims, in most cases. And, despite lots of other court cases happening throughout the extended history of Marvelman, there have as yet been no court cases to test any of those claims. Very shortly I’m going to attempt to sift through those claims, to see if I can get to some sort of conclusion, but first there is one more player in the game, who I’ve avoided mentioning until now, but who could be one of the most important people attached to the Marvelman character. When Jon Campbell bought Mick Anglo’s rights to Marvelman and subsequently attempted to tie up the loose ends by talking to people like Dez Skinn and Alan Moore, who had been involved with the Warrior version of Marvelman, he did get in touch with at least one other person from the earlier Miller-era incarnation who had also played a very important part in the life of Marvelman, but much earlier on.

My father’s company was L Miller & Son, Ltd, and he had the rights from America to publish Captain Marvel, Young Marvel, and the Marvelman Family, and they were quite successful.

It may or may not have been simply a slip of the tongue that he mentioned the Marvelman Family instead of the Marvel Family, but it was certainly an interesting slip, if it was.

It turned out that the person interviewing Arnold Miller at the BFI was a friend of a friend, and before long I had managed to actually find an address for him, and we began a postal correspondence about Marvelman that lasted for about six months, on and off, during which I found out that he had been approached by Jon Campbell with regard to Marvelman, although it did seem that, despite this, he really didn’t know too much about the modern history of the character.

This is his version of how Marvelman came to be created, and of what part Mick Anglo played in that creation, condensed from a number of different letters:

I am in the process of two projects, one being a company in Scotland, which is interested in publishing copies of the comics previously published by L Miller and Son Ltd. The other is, I am involved in a book on my life in the publishing business, and then later in the film business.

The real story as I remember is this, Mick Anglo was employed by L Miller and Son Ltd to write and draw story lines for Marvelman and the Marvelman Family comics, the rights to use the titles were given to L Miller and Son Ltd by Fawcett Publications. Mick Anglo has no copyright on the title Marvelman or Marvelman Family.

Fawcett were aware of L Miller and Son Ltd publishing and using the name Marvelman, Marvelman Family etc. Mick Anglo was commissioned by L Miller to draw material for the content, he has no rights to the cover material, this was supplied by Fawcett.

It seems as though Mick Anglo has a vivid imagination that extends far and above drawing. His meetings with Len Miller my father did not occur. I would mention that Mick Anglo was not flavour of the month with Florrie Miller my mother, who did not trust him.

I wrote to Mick Anglo and advised him that he had no copyright on the material he supplied and was paid for by L Miller and Son, and as I expected there has been no reply.

It seems there was another version of the origin of Marvelman after all.

Meanwhile, to answer the central question of Who Owns Marvelman – and indeed the related question of Who Owns Miracleman – it’s necessary first to decide what that question actually means, and which version of Marvelman and his alter ego Michael Moran we’re talking about – and it’s actually easier to refer to the different versions by that name, as it changes least. It would appear there are at least five versions of Michael Moran that we need to clarify the ownership of:

2: A modern version of this original character, now called Mike Moran, who was revived in Quality Communications’ Warrior #1 in March 1982;

3: The version known as Miracleman who first appears in Marvel UK’s Marvel Super-Heroes #387 in July 1982, only to be killed soon thereafter;

4: A republication and continuation of #2 who had his name changed to Miracleman, first appearing as such in Eclipse Comics’ Miracleman #1 in August 1985;

5: The Mike Moran who has a brief cameo appearance on the last page of Image’s Hellspawn #6 in February 2001, who was due to fully debut as Miracleman in Hellspawn #13, but never did;

6: There’s a possible sixth version, depending on what it is that Marvel Comics are planning for the version of Marvelman they appear to own – for the moment, this appears to be version #1, as listed here, but it’s possible they may create their own separate version of the character, based on that. They have, after all, said that ‘Marvel has stepped up to the plate to deliver on the promise of Anglo’s incredible characters,’ which can certainly be seen as their wanting to develop Marvelman for their own ends.

7: And a possible seventh version, as Marvel Comics also own the rights to the name Miracleman.

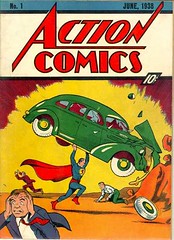

All of the later versions ultimately have the same point of origin, that of L Miller’s original Marvelman, who first appeared in Marvelman #25. But even the original Marvelman character is not particularly pure in his origins. There has never been any secret about the fact that Marvelman is a straight copy of Captain Marvel and, although it was ultimately never finally proven in court, Captain Marvel was held to be a copy of Superman. And Superman, of course, was often said to be based on Philip Wylie’s Hugo Danner from Gladiator. I shall, eventually, be trying to decide who own which of these versions, but there’s a bit more stuff to get through first. Such as…

As far back as you care to look, there seems to be some previous incarnation that has influenced what came after. So I’m going to start by looking at their possible relationship to Marvelman, and any claim their creator or copyright holder might or might not have on the character. Then I’m going to run through a few of the other names that have become attached to the character, more or less in chronological order, before finally getting down to the handful of people and companies that are left, and attempting to come to some sort of final conclusion.

Both of those characters are now owned by DC Comics, so the conclusion that DC has some sort of a claim on the character of Marvelman is an easy assumption to make. However, there is also the fact that DC appear not to have objected to the character of Marvelman at any point, neither in its original incarnation in 1950s Britain, when the metaphorical distance between the two countries was far greater than it is now (and they could be forgiven for never having even heard of Marvelman), nor in its later version in the 1980s, which they definitely were aware of, as it was in great part because of his work on Marvelman that DC contacted Alan Moore in 1983 to offer him work writing Saga of the Swamp Thing. DC could presumably still claim that Marvelman was a copy of not just one, but two of their properties – Superman and Captain Marvel – but would they be allowed to proceed with a case, seeing that they had not previously raised any objection to the character’s existence? This is one of the questions I don’t have an answer to, but my own opinion would be that they wouldn’t get too far with a claim that one of their characters was copied over half a century ago, and they’d finally decided to do something about it. There has to be some sort of statute of limitations on this kind of claim, and it seem likely that it would have passed by now.

One of the cases involving Neil Gaiman and Todd McFarlane would seem to point at three years being the window for someone to take action after being made aware that copyright was being claimed on a work, and that three years has run out for DC, except on the most recent edition of Marvelman, that published in hardcover by Marvel from August 2010, although they must have been aware of Marvel’s claim on the copyright at least from when the announced it quite loudly and clearly at San Diego in September 2009, so perhaps that three-year window is now closed also. (And, if there’s a similar rule in the UK… but I’m getting ahead of myself!)

For all that people have speculated over the years that DC might have some sort of right to claim Marvelman as their own, DC have never actually made any such claim, nor have they ever had anything at all to say about the character one way or the other, to the very best of my knowledge. Maybe they’ve seen how much trouble it has caused others over the years, and are quite happy to have nothing to do with it, and if so, who could blame them?

A question I really would like to have an answer to is, what happened at the moment of Marvelman’s creation? And who was present to witness it? Like a lot of things in this book, there is more than one version of the story. For a long time the only version of the creation of Marvelman came from Mick Anglo, the story of how he got a phone call telling him that the Millers had a problem, and urgently needed him to help them to solve it. Fawcett were withdrawing the Captain Marvel material, which was the basis of several of the Millers’ best-selling titles. Anglo says he went back to his studio, gave it some thought, and created a ‘Brit clone’ of Captain Marvel, called it Marvelman, presented it to the Millers, and voila! the problem was solved. The thing is, I’ve never been entirely happy with that version of events, and it always puzzled me that this seemed to be the only public version of the creation of Marvelman that there was, and that no-one seemed to have bothered to get an opinion either from someone at Fawcett or from the Millers, certainly not that I had ever seen.

It’s true that L Miller and Son Ltd had been publishing various different titles featuring Captain Marvel, and that this was making them a lot of money, so it would not have been to their advantage to have to stop doing so. Even so, it seems odd that they would go ahead with publishing what was essentially a direct copy of a character belonging to another company, particularly a company they had a good working relationship with – and who they would continue to work with for another 10 years whilst they were publishing a copy of one of their properties – without actually talking to them about it first. I always wondered if it was possible that Fawcett were aware of Marvelman, and perhaps even had a hand in his creation. And, from my correspondence with Arnold Miller, this actually appears to have been the case. So, the two versions of Marvelman’s creation are: on one hand, Mick Anglo’s, and on the other, Arnold Miller’s.

Anglo says that he created the character for the Millers after being asked to help them out when they found out they were to have their supply of Captain Marvel material cut off. Arnold Miller says that, although Mick Anglo came up with the idea for Marvelman, it was under the instructions of the Millers, and sanctioned by Fawcett. Both of them agree that Anglo’s Gower Street Studios – rather than necessarily Anglo himself – produced the work, but if he was more or less instructed in what to create by the Millers, who can be said to be the creator? Further, if the character he created was a direct and calculated copy of a previous character, can the secondary character really even be said to be a wholly separate character and creation, and to be subject to the same legal protection as a completely original character? These are the sort of questions that have kept me awake at night for several years now!

So here, as far as I can make out, are the two different versions of the creation of Marvelman, with perhaps a little dramatic license of my own thrown in.

The Arnold Miller version: At some point between Judge Billings Learned Hand’s judgement in August 1951 that Captain Marvel was a copy of Superman and late 1953, Fawcett Comics informed L Miller and Son that they would no longer be supplying them with Captain Marvel material for the British market. However, as the Captain Marvel comics were some of L Miller’s most popular products, Miller and Fawcett decided between them that they would come up with a copy of him, and hope that the British comic reading public would buy it. After all, it would still be about the only superhero comic in Britain. To help them in this, they called on comics’ packager Mick Anglo and his Gower Street Studios to do the actual supplying of the material for publication, based on guidelines from the Millers and Fawcett, with further input from Anglo and others.

The Mick Anglo version: The Millers were informed by Fawcett in late 1953 – more than two years after Judge Billings Learned Hand’s judgement in August 1951 that Captain Marvel was a copy of Superman – that they would no longer be supplying them with Captain Marvel material for the British market. The Millers were in a panic, and begged Anglo to help them out, as they were about to lose their most lucrative comic character. Anglo went back to his studio, gave it some thought, and came up with Marvelman, which he then supplied the Millers with for the next six years.

In a way, neither of these versions of the story is entirely satisfactory, and the truth probably lies somewhere between the two. There may, in fact, be a third version of the story. The Don Lawrence website says,

Don Lawrence was one of the first artists working on Marvelman. Together with Norman Light and Denis Gifford he was involved with the creation of Britain’s first superhero. […] Don is the creator of the spin-off Marvelman Family, which he had made up all by himself.

The idea that Don Lawrence was in it right from the beginning seems to be corroborated by Anglo himself, who called him ‘The first of the Marvelman artists.’ It is entirely possible that, when Mick Anglo went back to his studios in Gower Street on that day in late 1953, after being briefed by Len Miller about what he and Fawcett had decided they wanted Anglo to do, that, rather than puzzle it out on his own, he called together a few of his best people, and that they all put their heads together to see what they could come up with, and there seems to be strong anecdotal evidence from both sides to suggest that Don Lawrence was one of those people.

According to Don Lawrence, the material that Mick Anglo supplied, which was produced in his Gower Street Studio, was often not just drawn but also written by artists like himself, with Anglo overseeing the operation. So, at that point, who owned the copyright to Marvelman, and to the individual work produced?

What everybody agrees on is that the Millers replaced Captain Marvel with Marvelman, starting with issue #25 in February 1954, using material supplied by Mick Anglo’s Gower Street Studio. All of the comics that Miller produced carried a standard copyright notice to the effect that all stories and illustrations were the copyright of the publisher. That publisher was L Miller, of course. Although there is not a specific notice to the effect that the actual characters are copyright to Miller, there is certainly no notice that they are copyright to anyone else, and I think it’s safe to assume that the copyright notice for the stories and illustration was meant to extend to the characters in those stories as well. If nothing else, in the Britain of the nineteen fifties, rightly or wrongly, the rights for any characters published in comics would be automatically the property of the publisher, and even the concept – let alone the reality – of creators’ rights in the comics they created would probably have been virtually unknown. And again, it seems unlikely to me that the rights to Marvelman were Mick Anglo’s at that time, that he had somehow managed to end up owning the rights to a set of characters that was created at the behest of a publisher he was already doing work for on a work-for-hire basis, none of which other work is claimed as his. Fawcett, meanwhile, may or may not have had a hand in the creation of Marvelman, but they couldn’t exactly turn around and claim the character as their own, as that would mean they were acknowledging that they were in direct breach of their agreement not to publish any Captain Marvel material. It seems to me that, at that time, the only copyright notice that has any legal bearing on the character, and indeed the only one that actually existed, is the one claiming those rights for the publisher, L Miller and Son. Later on, though, circumstances would change, perhaps allowing Mick Anglo to claim the copyright for himself.

The legal position seems to be that that the rights would have become Bona Vacantia, which means ‘unowned goods.’ According to Wikipedia,

Bona Vacantia is partly a common law doctrine and partly found in statute. It governs property of deceased persons with no known heirs, the property of defunct companies and some failed trust property. In England and Wales, the Bona Vacantia Division of the Treasury Solicitor’s Department of the UK Government is responsible for dealing with bona vacantia assets except in the Duchy of Lancaster or the Duchy of Cornwall.

It is possible that the rights to Marvelman might not have become Bona Vacantia, if nobody even knew there were rights to the property to deal with. What I mean is, how could the Bona Vacantia Division deal with the rights to Marvelman if it didn’t even know about those rights? There is another old legal concept, called Res Nullius, which might cover this instead. Wikipedia says this about it:

Res Nullius (literally: nobody’s property) is a Latin term derived from Roman law whereby ‘Res’ (an object in the legal sense, anything that can be owned, even a slave, but not a subject in law such as a citizen) is not yet the object of rights of any specific subject. Such items are considered ownerless property and are usually free to be owned.

And an online Legal Dictionary adds this (with emphasis by myself):

RES NULLIUS. A thing which has no owner.

A thing which has been abandoned by its owner is as much res nullius as if it had never belonged to any one.

So, did anyone actually own Marvelman?

Next week, I want to further examine Mick Anglo’s part in the creation of Marvelman, along with others.

To Be Continued…

Okay, Padraig, this from my world:

“Once a copyright has played its part in inducing creation and compensating the creator, and after a specified term of years, the work is turned over to the management of the public domain, where, in contrast to the limited perspectives and goals of a sole copyright owner, countless users are free to exercise their ingenuity in ferreting out the work’s hidden potential in the form of adaptations, performances, and other transformative uses.

“[A bloody history of] legal protection can scarcely be justified on any theory consisting with copyright’s core pragmatic purpose of adding a dash of economic incentive to the other attractions of authorship. Overlong copyright terms inspire misconceptions about the nature of intellectual property, causing copyright owners and the public alike to think of copyrights as family heirlooms or corporate entitlements. But grandmother’s brooch was never intended to play the important social and cultural role for which a creative work is destined.

“Indeed, it could be argued that a work does not really become a ‘classic’ until it is unqualifiedly available for culture exploitation.”

-This from attorney Robert Spoo on the intricacies of copyright regarding James Joyce’s ULYSSES (my own area of obsessiveness).

It does seem clear to me that the arguments over ownership you’ve exposed are rather circular and bloody. They relate to the idea that MARVELMAN existed as something prior to the revisions of 1982. I’m glad to see you bring in the argument about Res Nullius as, frankly, I think that’s the case regarding that original material of 1954. It could be Dez Skinn thought he could get away with it, could be Mick Anglo said sure, could be many “unknowable unknowns” about the discarded status of the 1954 ownership.

But its mostly clear that Alan Moore was looking to make a new thing out of an old thing (much as Joyce had with Homer) when he approached the work published in 1982. And, I think its worth stressing this point again, he was doing it in a freshly open field of “creator rights”. I believe that he went into the task with full conviction that he wasn’t screwing Mick Anglo or anyone else over.

But the work he and Gaiman and the others did is the modern material of question, the real work of substance. The roadblocks being set up to keep that work from publication are about the narrow-minded view of copyright Spoo describes above.

And the ridiculous, petty, boisterous, chest-thumping claims of Todd McFarlane of course, who proves himself the most shallow of artists by insisting that the creativity of others can possibly be purchased at auction.

-R

Wow! This installment (and Robbery’s comment) are the favorite things I’ve yet seen written here on this subject. My take-aways: (1) Anglo sounds more like a studio boss than a “creator”, writer, or artist; (2) Marvel sounds like it paid something for nothing to secure Anglo/Campbell’s supposed rights; (3) Dez Skinn sounds like he had a good faith Res Nullius basis to believe the abandoned MM property was legitimately ripe for re-use; (4) I don’t see how that would justify Skinn appropriating the old Miller copyrights from out of the public domain, but the way seemed clear from him to re-trademark the “Marvelman” name and copyright new works.

I vote someone tries to publish a Marvelman comic they’ve written and let’s see who sues.

This is NOT how the Copyright Laws work. Maybe there are small differences in the United States.

The new Miracleman and new Marvelman are all DERIVATIVE works from the original Marvelman. To “own” the new Marvelman would require ownership of the original copyright. IF it had entered the public domain then you CAN own the derivative works as a new work, see Universal’s portrayal of Frankenstein and many others.

In this case, and I am not going to look up British copyright law, and it is clear Anglo is lying about the earlier drawing, the obvious conclusion is that the rights went to the Crown and that they are STILL sitting with he Crown.

Sorry, there is no Res Nullius doctrine that applies to copyright. NONE. Copyright is an intellectual property law and property whether real or intellectual does indeed reflect a chain of title. It cannot be “abandoned” and you can research the very real problem of “orphaned” copyrighted works.

The rights to Marvelman (the original) sit with the British government.

Now if somebody wanted to spend large sums of money to get these rights they could do so. Then they could approach Skin/Moore/Buckingham etc and claim that they retroactively violated their copyright and unless they release their rights to the derivative work (which are valid) they will sue. ALL of them will relent.

Then you go to Marvel and inform them that the publication of the collections of crap they released violates your newly bought rights. The new regime will cave in less than 45 seconds.

Now, having spend minimum 100,000$ to do all of this, you own Marvelman, a character beloved and demanded by all of 922 people. I hope you feel good about that!

“If Captain Marvel was created today, he would be only one of many super-powered comic characters, but in February 1940 there was no escaping the fact that he was created to try to cash in on the fame and popularity of Superman.”

You’re confusing two ideas here. Just because something is created to try to “cash in on the fame and popularity” of something else, doesn’t make it a violation of copyright law.

You should talk to some people who know the history of the Superman/Captain Marvel situation. I think you’re extrapolating from a faulty premise.

Yeah, I was going to say the same thing. The publisher might as well have told CC Beck “give me a Hercules” and in fact, Capt. Marvel’s origin and Superman’s are nothing alike, really. Capt. Marvel is much more inspired by magic and things like the 1001 Arabian Nights.

DC would never go after Marvelman for the same reason they never did anything about the Squadron Supreme.

Padraig – You should read Milan Kundera’s non-fiction books The Art of the Novel and Testaments Betrayed. There’s a lot of stuff in them about the history of fiction and inspiration and the idea of anything being “original” in the first place. I think your thoughts on Marvelman, Watchmen, The Superfolks, etc. would benefit from his perspective.

In the back pages of Fatale and Incognito, Jess Nevins has written a lot about the history of pulp characters and publishers, and it’s clear that most pulp heroes were created by a publisher going “The Shadow is selling like hotcakes, we need a Shadow-like character.” But that didn’t make The Spider a copyright infringement on The Shadow, because he was a totally different character, just like Moon Knight and Batman are.

>> DC would never go after Marvelman for the same reason they never did anything about the Squadron Supreme.>>

Actually, they’ve done things about the Squadron Supreme numerous times, and it’s always been resolved behind the scenes.

There was one point where someone pitched the idea of doing a Squadron maxi-series in which their plan was to re-do early JLA stories with more modern dialogue and characterization. I doubt Marvel would have gone through with that idea, but DC got wind of it and told Marvel not to. And when Mark Gruenwald did his Squadron project, DC complained, so Marvel agreed to make changes to make it less like the JLA, which is why Mark changed character names, killed off some characters and had others join. [He also scrapped plans to introduce the Skrullian Skymaster because DC specifically objected to that, and then someone else later brought the guy in anyway.]

So it’s not true that DC never did anything about the Squadron. Basically, if the Squadron is treated as a parody, they don’t kick about it, and if the Squadron’s changed to be clearly something other than the JLA, they won’t kick about it. But serious Squadron stories that look too much like JLA stories get them annoyed, and they do take steps at that point.

I’d say DC hasn’t done anything about Miracleman/Marvelman because they didn’t own the Fawcett Marvels until 1991 (they licensed the characters earlier), and by that point, the stories and character treatments simply weren’t close enough to what they own to object.

Perhaps the oddest thing about the question of who owns the copyright to Marvelman is that the copyright has a negligible value to anyone unless there’s a demonstrated demand for Marvelman product(s). Is there anyone in the world holding back on producing Marvelman merchandise, cartoons, video games, or movies because of uncertainty about the copyright?

The reborn Valiant was recently in the news about the possibility of reviving some of the old (old, old) Gold Key heroes. It’s not a criticism of the concepts to think, “Who gives a damn?”

Marvelman, the Gold Key heroes, and other defunct characters are arguably worth less than any creation produced by a current writer who has a story he wants to tell. If the story is worth publishing, there’ll be a market for it.

SRS

“Marvelman, the Gold Key heroes, and other defunct characters are arguably worth less than any creation produced by a current writer who has a story he wants to tell. If the story is worth publishing, there’ll be a market for it.”

Not to disagree to strongly with that statement, but I think its important to remember the work in demand, the post 1982 MARVELMAN, was penned by two of the biggest names ever to sell comicbooks. Other works by each of them dating from around the same time have managed to stay in print, and stay strong as sellers, for thirty years.

Add to this the fact that Neil Gaiman, who doesn’t do much comic writing anymore, has been pushing for some movement on the copyright issues because there’s a lot more story there that he wants very much to tell. That’d be a big item for any publisher whether the character is latter added to some kind of existing universe (SENTRY) or not.

Its a very messy property for all the reasons (and more) that Padraig has cited in previous articles, but still a very sexy series of graphic novels with very big talent behind it.

Oh, and speaking of big talent, Ed Brubaker makes a great call on the nonfiction work of Milan Kundera. ART OF THE NOVEL in particular. I think he’s right, Padraig, that following the lines of original concept for the super man as you do from Phillip Wylie is a bit jumbled and needs some rethinking. There’s a real desire to explain something like this in a book like the one your proposing here, but its a slippery slope pull readers astray. It seems that the real question is “who owns MARVELMAN?” and not “who thought off it first?”

As one of the US readers who had never heard of Marvelman until now, this saga has got to be more interesting than anything the character has ever done. Reminds me of who owns the copyright on the King James Bible, a similarly inscrutable mystery that spans two continents and innumerable publishers. Or maybe Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. If nothing else, this is an argument in favor of reforming intellectual property laws. If no ownership can be determined, or more than one party has equal claims to ownership, the character should be in the public domain.

Thank you all for your comments. First of all, before I get to them, let me state absolutely and categorically that I am not any sort of a lawyer, and particularly not an expert on copyright law, in any jurisdiction. So any opinion, like I said above, is just that, my opinion. However, I’ve asked a few people about stuff, and read what I could find – and understand! – to try to inform that opinion as much as I could. So I’m not completely shooting in the dark, I hope.

robberry : I do know that Stephen Joyce, the grandson and literary executor of the James Joyce estate, was extremely tedious to deal with. Anyone who had dealings with literary matters over here – and I believe particularly the lady whose job it was to issue checks from the copyright authority in Ireland, who continually had him hounding her, from what I heard on the mean streets of Dublin’s book slums – all had a big party on the 1st of January 2012, when it all went into the public domain, simply because they’d never have to deal with him again. So I imagine that was at the back of a lot of that piece by Robert Spoo you quoted – a wonderfully Joycean surname, too, and almost too good to be true.

Yes, ‘Alan Moore was looking to make a new thing out of an old thing […] when he approached the work published in 1982,’ but the old work was always central to that new story. Indeed, the idea of what happens to superhero characters from an older time exposed to modern times runs throughout his work in the field.

And, re ‘the ridiculous, petty, boisterous, chest-thumping claims of Todd McFarlane,‘ it’s one of the many mysteries of MM – why did McFarlane make such a huge fuss about a property that he never worked on?

Molnek says:: ‘I vote someone tries to publish a Marvelman comic they’ve written and let’s see who sues.‘ Off you go! We’ll be right behind you…

Don: As I said above, I’m no expert on copyright law. However, I did have a quick look at something about Orphan Works, and it does seem that the concept applies more so in the US than elsewhere, and that it really only dates from the mid-1970s, so the Millers winding up their business and MM becoming ‘ownerless’ pre-dates any applicable legislation, on either side of the Atlantic. The plan of action you lay out – getting everyone who had dealings with the property to sign releases – seems to be exactly what Emotiv did, prior to selling what they had acquired to Marvel.

John Warren: You’re confusing two ideas here. Just because something is created to try to “cash in on the fame and popularity” of something else, doesn’t make it a violation of copyright law. Yes, I see what you’re saying. I did go through the situation regarding Superman and Captain Marvel in some detail in an earlier chapter, but I certainly concede that I didn’t express that as clearly as I could have. Of course, one of the things that complicates the Superman/Captain Marvel row is that it never got finally resolved in court. And it was the stories that were held to be in breach of copyright, rather than the characters.

Ed Brubaker: You should read Milan Kundera’s non-fiction books The Art of the Novel and Testaments Betrayed.‘ OK, duly noted! Thanks very much.

And, as noted above, it was the stories, rather than the characters that were allegedly in violation. The characters of Superman and Captain Marvel were definitely different, for all sorts of reasons, including their origins. I think I point out a lot of them in the piece linked to above. It’s a shame CM was done away with at the time, because he seemed like a lot more fun that the prissy Kryptonian.

Jess Nevins is a friend, and I have a lot of his work on pulp heroes, although mostly sadly unread!

Kurt Busiek : ‘I’d say DC hasn’t done anything about Miracleman/Marvelman because they didn’t own the Fawcett Marvels until 1991 (they licensed the characters earlier), and by that point, the stories and character treatments simply weren’t close enough to what they own to object.‘ And, really, do they want to get involved in this unbelievable multi-dimensional clusterhump? I’ve not been a huge fan of DC for some of their corporate policies, but staying out of this may be the smartest thing they’ve done.

Synsidar: ‘Perhaps the oddest thing about the question of who owns the copyright to Marvelman is that the copyright has a negligible value to anyone unless there’s a demonstrated demand for Marvelman product(s).‘ Yes, a very valid point. I really hope that, when they eventually get around to doing whatever it is they’re planning to do, it keeps fine for them. At this point there must be huge amounts of money that need to be recouped on this, before they even break even on it.

Big names to some people, but not to others.

It’s bizarre to see the ways in which Marvel and DC endlessly try to recycle failed concepts. People at Marvel, for example, apparently think that Defenders has some sort of magical quality, so they publish DEFENDERS series again, again, and again, and watch them fail again and again. If they were to do basic market research, they’d probably find that Defenders is poisonous to readers who have been turned off by previous attempts, and not particularly attractive to new readers. Why keep using the word?

DC’s canceled its Firestorm series again. A blogger noted the cancellation, and hoped that the character would fare better when DC tried a Firestorm series again–why? Why try again?

When low-rated TV series are canceled or books sell poorly, how many people shed tears over the failures? They generally go on to other projects. But people in comics treat series characters differently, as though they’re so entranced by the visual concepts or so eager to have a job working on the character that they’re simply unwilling to accept failure. The endless recycling makes the companies publishing superhero comics look bad.

SRS

The history of Marvelman is interesting, but the similarities to other characters are significant only, I think, in the context of superhero comics, in which a single character is the foundation and the focus of a series. The similarities cease to be significant when a writer does a standalone story with him, simply because the details in the standalone story will dwarf those in the series.

The Squadron Supreme–a writer could do a straight parody of the JLA, or he could do a serious story. Adding a few characters not in the JLA and focusing on relationships would diminish the similarities to the point that they would be insignificant.

Doing a Superman analogue would be trivial in a standalone story, because conferring the status of “the world’s premier superhero” upon him and giving him multiple powers would be sufficient for the writer’s purposes, without duplicating any specific aspect of Superman. Whether there’s anything particularly interesting to say about “Superman” in a standalone story that doesn’t end tragically or depressingly–that might explain why Superman analogues are pretty rare in fiction.

SRS

I bought the Marvelman trademark from a homeless man outside of the Greyhound bus station in New York City in early 2004, for the sum total of the rest of my soda pop and a couple of cigs. True story.

As far as the intellectual property rights go. The statute of limitations for copyright infringement in the US is 3 years after the infringement is discovered.

While the true ownership of Marvelman is unclear, I cannot forsee a situation in which the true owners (once ownership is resolved) can bring a retroactive infringement lawsuit as suggested by Don Murphy … at least in the US. The US system is based upon placing the onus upon the owner of to protect their own intellectual property rights. If the true owners failed to assert their rights by virtue of being unaware that they were the true owners, such a failing would prevent them from retroactively pursuing an infringement action.

>Big names to some people, but not to others.

Big names to enough people to ensure some sort of healthy shelf-life at the shops. Again, these are two authors with a significant presence in bookstores and specialty stores – often two of the few authors who get an entire shelf or case in the shop devoted to their work. Probably the two most widely-read authors in the industry between Watchmen and Gaiman’s prose work.

And, again, this is also a discussion about Gaiman’s unfinished work which has interest to some (not to me, clearly not to you, but to some). It’s not the same thing as Yet Another Firestorm comic (obvious diminishing returns aside). I’m not interested in Sherlock Holmes pastiche or new endings for the Mystery of Edwin Drood, but if you told me Doyle insulated his home with unpublished Sherlock Holmes stories or Dickens hid the real ending of Edwin Drood in a secret vault, then I’d line up for the chance to read them; and, to some fans, so it is with Gaiman’s Miracleman.

“Big names to some people, but not to others.”

Marvel doesn’t have the sort of evergreen backlist titles that DC does with Watchmen and Sandman or Dark Knight Returns (and to a lesser extent V for Vendetta), even though their films have grossed billions. Clearly, someone at Marvel sees a set of Moore and Gaiman Marvelman trades as having that potential. Based on the ebay prices for the comics and TPBs there is some level of pent up demand for those stories.

Of course, not every Moore or Gaiman collection has the juice that Watchmen and Sandman have. I haven’t looked up the numbers, but I doubt that Books of Magic, or Black Orchid, or Promethea or League of Extraordinary Gentleman have torn up the sales charts in the last decade.

“Of course, not every Moore or Gaiman collection has the juice that Watchmen and Sandman have. I haven’t looked up the numbers, but I doubt that Books of Magic, or Black Orchid, or Promethea or League of Extraordinary Gentleman have torn up the sales charts in the last decade.”

But the collections of all of these have been continuously in print since they were first published, which is itself the sign of writers with a healthy following and shelf-life.

I think its safe to say that anything with the words “Neil Gaiman” on the spine will stay in print for the foreseeable future, and Alan Moore is right about there too. Synsidar, these are both HUGE names in publishing and to readers and book buyers.

Yes, I was about to say something very similar. It’s simply disingenuous to say something like big names to some people, but not to others, when we’re talking about Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman. How big do they have to be??

” Even so, it seems odd that they would go ahead with publishing what was essentially a direct copy of a character belonging to another company, particularly a company they had a good working relationship with – and who they would continue to work with for another 10 years whilst they were publishing a copy of one of their properties – without actually talking to them about it first. ”

However, you have to keep this in context. Miller was creating a clone of Captain Marvel, a Fawcett property, which is something that Fawcett would normally be interested in preventing. However, for all intents and purposes, the Captain Marvel property was essentially worthless to Fawcett based upon their settlement with DC. Fawcett might not have wanted to waste resources to protect a property that was going under anyway.

Who owns Marvelman? Is that really the question that concerns people?

I’m only interested in who owns the rights to reprint Eclipse issues 1-24.

Is that the same question, or are the two matters not necessarily synonymous?

I don’t need Miracleman to join the Avengers. And I don’t need the old Anglo stories reprinted. I’m only interested in a nice reprinting of 1-24.

BTW, I understand Neil wants to continue the story he started. BUT, would anything stop him from writing those stories using a Miracleman doppelganger (ala The Sentry, or even a ‘new’ character called simply ‘Marvel’)? He could even start it with issue #25, and Marvel could sell it with a wink-wink-nudge-nudge firmly attached.

I agree that Moore and Gaiman are big names in the publishing world, but to many superhero comics fans, they’re credits. Neither man is ever going to write the Superman story that ends his publishing run, and there’s no particular reason for either one to do a WFH story unless a particular situation piques his interest to an unusual degree. The editorial philosophy at both Marvel and DC is that the characters are more important than the talent–and that’s the reason, I suppose, for the constant recycling of characters.

If someone gave me Gaiman’s Miracleman storyline to read, I’d take a look at it, but I have no interest in seeking it out. There’s plenty of other material by both creators I can read, that features their creations.

SRS

“But the collections of all of these have been continuously in print since they were first published, which is itself the sign of writers with a healthy following and shelf-life.”

Sure. Gaiman is probably the only author that can put a non-superhero GN on the NYT best seller list, and I don’t think there is a bigger name in comics than Moore. But Marvel doesn’t invest an alleged $1 million for intellectual property rights on the next 1602 or Eternals or Captain Britain (all of which I’m fairly sure have gone out of print for Marvel at one time or another). Marvel is swinging for the fences here. If it gets a finished Silver Age and Dark Age into print, I’m all for it, but I can see a lot more reasons why 6 Marvel man collections would not do nearly as well as Watchmen or Sandman.

“There’s plenty of other material by both creators I can read, that features their creations.”

Probably more true of Gaiman than Moore and even then Moore’s Marvelman has less to do with Mick Anglo’s than Supreme does with Superman. The vast majority of Moore’s work is him either doing other people’s creations or riffing on other people’s creations. V for Vendetta is the only major exception that comes to mind.

>> Gaiman is probably the only author that can put a non-superhero GN on the NYT best seller list >>

SCOTT PILGRIM vol. 3 is #2 on the list right now. Also on the current list: A TWILIGHT GN and THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO.

In recent weeks, the list has featured 100 BULLETS, THE RAVEN GIRL, MARBLE SEASON, MIND MGMT, WALKING DEAD, A WRINKLE IN TIME, JERUSALEM, 50 GIRLS 50, BUILDING STORIES, AMERICAN VAMPIRE, CHEW, ARE YOU MY MOTHER and more non-superhero stuff.

kdb

“When low-rated TV series are canceled or books sell poorly, how many people shed tears over the failures? They generally go on to other projects.”

SRS: Have you ever met anyone in the Firefly / Pushing Daisies / Veronica Mars / Wonderfalls / Arrested Development fandoms? (Personally, I’m still upset EARTH 2 with Tim Curry only had a single season.)

PM

Emotiv did go to the others involved, based on their own claim to owning the false copyright of Mick Anglo.

I would buy a nice reprint of the Moore Marvelman at once, no question, but I would never buy a “new” Marvelman. And I guess I am not the only one. Marvelman has a definite ending, so any continuation is just pointless. Not that that would stop Marvel from doing this, but it is hard to imagine that this property would ever repay the investments.

Also never underestimate the appeal of the art. Unlike Watchmen or Dark Knight this would be a collection of very different styles, one of them not very good, so regardless of Moore I can’t imagine that this would have the legs to be the longseller Watchmen is.

“SCOTT PILGRIM vol. 3 is #2 on the list right now. Also on the current list: A TWILIGHT GN and THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO.

In recent weeks, the list has featured 100 BULLETS, THE RAVEN GIRL, MARBLE SEASON, MIND MGMT, WALKING DEAD, A WRINKLE IN TIME, JERUSALEM, 50 GIRLS 50, BUILDING STORIES, AMERICAN VAMPIRE, CHEW, ARE YOU MY MOTHER and more non-superhero stuff.”

On the GN list? Fair enough.

It wasn’t as clear as I thought from the context, but I was referring to the hardback fiction list. Sandman: Endless Nights did hit that. It would only be fair to include the fiction trade paper list as well. It wouldn’t surprise me if Scott Pilgrim or Walking Dead hit that list.

And to be fair, given the addition of the graphic fiction lists, I’m not even sure that a GN can make a general fiction best seller list at this point. If that’s the case, consider the comment withdrawn.

Comments are closed.