Poisoned Chalice Part 2:

Marvelman – The Miller Years I

[Previous chapters: Introduction, 1: Prehistory]

Within a few months of the first ‘modern’ format comic books hitting American newsstands, they also appeared in Britain. Although there was no official distribution of [American] comic books, or any other periodicals for that matter, in Britain, large quantities did arrive on British shores nonetheless.

Most of them ended up in the hands of marketplace book and magazine dealers but some actually were distributed through the Woolworths discount chain. In Britain, the American 10¢ cover price was meaningless. American comics sold at Woolworths for two pence or roughly 6¢ at the 1939 exchange rate. For British children American comics were an exotic novelty. There was nothing even remotely like them on the British market even though some British comics began using American reprints as early as 1937.

Later on Gore says,

As awareness of ‘real’ American comics grew, so did the British demand for them. Both TV Boardman and Gerald G. Swan were quick to capitalise on the American publications, securing them from shipping companies and distributing to various sales outlets. The success of this venture was short lived, however. The start of World War II on September 3, 1939, put an end to the quasi-official import of American periodicals, even as ballast.

It was the British declaration of war on Germany in 1939 which provided the impetus for British comic companies to begin to publish their own American reprints, as it had the effect of immediately halting the importation of American comics into the United Kingdom to allow room for higher priority cargoes.

All the above hopefully relevant potted history of British comics, and general scene setting, finally brings me around to the future publisher of Marvelman, Leonard Miller.

Len Miller, the boss, started out literally as a street trader by selling various small-time British publications and American import titles brought over as ballast on ships. He sold these from two humble canvas-topped stalls situated on the corner of Cambridge Road in Whitechapel, London, in the 1920s. Well, as a schoolboy, on Saturdays I used to buy from Len small serialized Western comics from the USA at 1d each […] I loved reading those old yarns and would go home, sit on my bed, and devour them!

Len Miller eventually became a wholesaler and distributor and, after Britain entered the Second World War in 1939, he became a publisher as well, publishing pretty much anything he could get his hands on, occasionally sourcing original work in the UK, but usually concentrating on reprints of material bought in from the USA. Although he’d been publishing virtually since the war broke out, it wasn’t until 1942 or 1943 that he finally legally formed the company L Miller and Son Ltd, along with his son, Arnold Louis Miller, then twenty one-years old. The company spent most of its working life in their warehouse at 342-344 Hackney Road, in Hackney in North London.

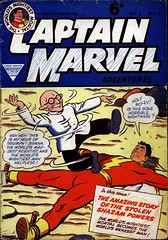

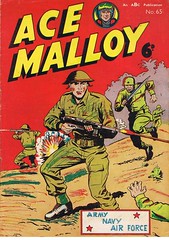

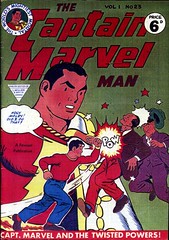

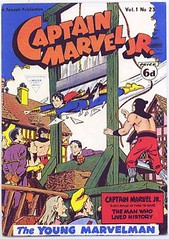

And, unsurprisingly, their most popular comic was Captain Marvel, along with its related titles. Actually, after their first reprint comic of Fawcett material, that unnumbered issue of Wow Comics in 1943, their next titles from Fawcett were all Captain Marvel related: Whiz Comics, Captain Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr, and Mary Marvel, all in 1944. Later on, in 1946, they would add The Marvel Family to this list. All these titles, much like the rest of the Millers’ output, were originally published sporadically, with no real consistency of numbering, all the way up until 1950, when they re-launched some of the titles on a monthly schedule. Miller had a habit of starting the numbering of some of his comics at #50, so Captain Marvel ran from #50 in 1950 to #84 in 1953, Captain Marvel Jr ran from #50 in 1950 to #85 in 1953, and The Marvel Family ran from #50 in 1949 to #89 in 1953. These titles were by all accounts hugely popular.

I have to say, ever since I started looking into all this more closely, this particular situation has always puzzled me. The Millers had been doing business with Fawcett for ten years at this point, which was presumably profitable for both parties involved, and one would imagine that they would have built up a closeness over those years, or at the very least a strong and amicable business relationship. None the less, it certainly appears as if the Millers weren’t aware of Fawcett’s problems with DC until quite late. It had been at the end of August 1951 that Judge Learned Hand had stated that Captain Marvel was, after all, a copy of Superman, and in 1952 Fawcett had settled out of court with DC, which is when they undertook never to publish Captain Marvel again, and when the first of the Captain Marvel titles was closed down. Why did it take until late 1953, two years after Judge Hand’s judgement, for the Millers to learn of this? I know that the Atlantic was, metaphorically speaking, a lot wider in the early ‘fifties than it is now, but even so it strains credulity to think that Fawcett would not have mentioned to an old and valued customer that the most popular characters they both had were soon to be no more until well after this had come to pass.

Also, presumably the Millers didn’t just wake up one morning and change the schedule on the Captain Marvel titles from monthly to weekly, so there must surely have been a certain amount of time before the re-launch in the middle of August 1953 when they would have planned this, which surely should have involved them informing Fawcett in America that they were doing so, and talking about getting more material from Fawcett’s back catalogue – by this time, Captain Marvel and related characters had been running for a dozen years in at least nine different titles, so Miller could only have published a fraction of what was available – but this also appears not to have been the case. Indeed, it appears from all the available evidence that neither side spoke to the other, meaning that the Millers suddenly found themselves with a hugely popular group of comics that were very soon to have their contents irreversibly cut off. They certainly didn’t want to give up their most popular characters, and most valuable properties, but what could they do? What they did, apparently, was call Mick Anglo.

Mick Anglo was born Maurice Anglowitz in the Bow area of London’s East End. He claims he was born on the 14th of June, 1916, even though his birth certificate gives the date as the 19th of June. After school in the Central Foundation Grammar School in Cowper Street in Islington, Mick got a scholarship to the Sir John Cass Art School in Aldgate. He left school at eighteen and eventually got some freelance work drawing clothing designs for one of the London fashion houses. In 1939, at the age of twenty-three, he enlisted in the army at Oxford, becoming an infantryman in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and at one point found himself working as a cartographer at Earl Mountbatten’s headquarters in Sri Lanka.

As I recall, it was a still drab post-war Britain, and I’d been doing this, that, and the other to keep body and soul together. One day in the early 1950s, my next-door neighbour showed me a couple of bright American-style comics bearing the distinctive triangular logo L Miller and Son, an English company, with a 6d price on them, and he suggested I check them out for some further artistic work. I duly visited their warehouse headquarters in Hackney Road, London, and was fortunate to meet the son, one Arnold Miller, who, it turned out, had formed his own branch of the company to publish original British space comics, as the bulk of the lines up until then were American reprints, such as Captain Video. Anyway, he was raring to do a series under his own banner ABC (Arnold Book Company), and I was very interested, as you can imagine. I showed him some of my work I’d brought along, though what it was escapes me, and he was suitably impressed. It was then, during discussions, to my surprise I discovered that the boss, Arnold’s father Len, was in fact the same man who once sold me comics as a kid! […] After some in-depth discussions re could I create such-and-such and find other artists, etc, things started to buzz, and very soon I formed Mick Anglo Limited, and found myself searching for suitable premises for a studio. Eventually I located some rooms at the top of a rickety flight of stairs in an old building at 164 Gower Street, London NW1, long since demolished, which became the Gower Street Studios.

Some of the dates for events Anglo mentions in the above quote don’t quite line up, however. In the Marvelman article in Nostalgia he says, ‘At the beginning of the fifties I had a studio in Gower Street, Euston,’ which is fine as far as it goes, although also maddeningly vague. However, documents from Companies House in London show that Mick Anglo Ltd wasn’t registered until the 21st of August 1954.

And all of that might explain why the Millers called Mick Anglo when they had their problem with Captain Marvel at the end of 1953, even though he’d only been working for them for a year, at that point. He was one of the only people in the UK running an American-style comics studio, and, at the age of thirty-seven, had a lot of experience in the field and a huge body of work behind him, both for the Millers themselves and for lots of other people besides. He recalls the events at the end of 1953 in his two main biographical sources, Nostalgia in 1977 and Alter Ego in 2009. Firstly, there’s Nostalgia, where he says,

Among Len Miller’s most successful series were the Captain Marvel titles, reprints of Fawcett’s of New York: Captain Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr, The Marvel Family, and Mary Marvel. One day Len phoned and said he wanted to see me urgently. Fawcett’s were involved in some legal trouble with Superman over Captain Marvel; an injunction had been slapped on them, and Len said it looked as if his supply of American material for Captain Marvel would be cut off. Had I any ideas

Meanwhile, this is what he had to say in Alter Ego:

One day in late 1953, I think, the Millers rang me to say, ‘Come over, Mick – urgent – very urgent!’ I went to the warehouse premises, and much consternation! Len was in a right old mood. It seemed that in the USA Fawcett had lost a court fight with Superman comics, etc, and could no longer market their Captain Marvel character; thus Miller, in turn, wouldn’t receive further supplies of the comic plates to print Captain Marvel. They held the license to reprint the comics in Britain, and he was one of their very lucrative lines. This created big problems! […] So boss Len needed a substitute real fast and could I come up with something?

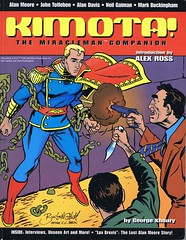

Mick Anglo says that he went back to Gower Street and thought about it, and decided that what they needed to do was create a British copy of Captain Marvel to step into his shoes, and to carry on instead of him. The character Anglo suggested to take Captain Marvel’s place was virtually a carbon copy of him. The name Billy Batson was turned into Mickey Moran, with Moran becoming a young copy boy for the Daily Bugle newspaper, as opposed to Batson’s position as a reporter for Radio Whiz; the costume was changed from red to blue, and the cloak was done away with; the dark hair became blonde; the magic word SHAZAM!, given to Batson by the wizard Shazam, was replaced by the word KIMOTA! – a slightly altered back-spelling of the word ATOMIC – given to Moran by Astro-physicist Guntag Barghelt. All that was needed was a name. According to Derek Wilson’s article From SHAZAM! To KIMOTA! – The Sensational Story of England’s MARVELMAN – The Hero Who Would Become MIRACLEMAN, also in Alter Ego #87,

The first name change suggested – and most obvious one – was finally adopted […] although other names were seriously considered, including Miracleman and Captain Miracle, which were registered as possibilities.

That ‘first name change suggested’ was Marvelman.

In a lot of ways, though, Marvelman was more like Superman than Captain Marvel. Like Superman, his powers were science-based, rather than being magic-based, like Captain Marvel’s. Like Superman, he had his initials on his chest. And his name owed at least as much to Superman as it did to Captain Marvel, being a single word name with ‘-man’ at the end. Unlike either of his predecessors, however, Mickey Moran didn’t seem too obsessed with people seeing him change into his alter ego. Perhaps this was a difference caused by it being produced in Britain, rather than in America. After all, in America, a lot of people had a sort of duel identity of their own, being Irish, or Italian, or Jewish, or whatever their old identity was, as well as being their new American identity. And a lot of them were just like Superman, a stranger in a new land, so issues of identity would be more relevant – closer to the surface, perhaps – in the American psyche than they were ever likely to be in England.

Mick Anglo gives his version of the creation of Marvelman in various places. In Alter Ego he says,

I went back to Gower and […] I gave it considerable thought and eventually came up with the idea of a Brit clone. I worked out a storyline, and so it was that Micky Moran, a teenage copy boy at The Daily Bugle, becomes Marvelman by shouting the all-power-producing word KIMOTA which of course is ATOMIC spelt backwards, using K for a stronger sound.

Yes, it was my creation except everything is based on somebody else. A bit of this and a bit of that. With Superman, he’s always wearing this fancy cloak with a big ‘S’ on his chest […] I did away with the cloak so that I didn’t have to draw the cloak, which was awkward to draw, and played with a gravity belt, and they could do anything without all these little gimmicks.

Presumably Anglo’s suggestion was approved by the Millers, so their next task was deciding how to handle the change over from Captain Marvel to Marvelman. In Nostalgia, he says,

In the last of the Marvel titles we announced that Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr. were so well known as marvelmen that in future they would be known by the titles Marvelman and Young Marvelman and would each have a weekly comic of their own, and the Marvel Family would henceforth appear as the Marvelman Family in a monthly comic.

Bizarre as it may now seem, this is exactly how they did it. In Captain Marvel #19 and Captain Marvel Jr #19, both cover-dated December 23rd, 1953, there was an announcement to the readers, purportedly from Captain Marvel himself, that said that Billy Batson and Freddy Freeman were both going back to their lives as normal boys, but that they had found two replacements for themselves, called Marvelman and Marvelman Jr. This is what appeared:

Dear Boys and Girls,

I can hardly wait to tell you of the most startling and astounding news I’ve ever had the good fortune to announce. Seeing as how this is Christmas week, it has come at a most fitting time.Holy Moley! I can almost hear you saying, get on with it or we’ll never know what it’s all about. Sorry, chums, it’s just that I’m a bit excited – but here it is.

Boys and girls, it is my great pleasure to introduce Marvelman – what, another of the Marvel family – well, yes, in a way, for you see Marvelman is going to step right into my shoes. He is to follow the Marvel tradition of finding and fighting evil wherever it exists.

Now I guess you’re all wondering where I fit into this; please allow me to explain. For an awful long time I’ve been worrying about Billy Batson. Billy, as you know is a grand boy, and I feel he is not being given a break. In other words, a chance to grow up. I went along to old Shazam and told him my worries, and between us we’ve decided to give Billy the chance to settle down. In order that this might be achieved, I shall soon be returning my powers to old Shazam and changing into the character of Billy Batson for the last time. This will give this grand lad a chance to develop into the type of citizen that I know you’ll grow into.

Naturally we couldn’t leave the door of the world wide open for evil – hence Marvelman of whom I feel you’re just busting to know more. What could be better than to ask him to say a few words to you. It’s all yours, Marvelman:

‘Well, this is great. I mean my being able to introduce myself even before my adventures are being read, and I sincerely trust that you will follow them as closely as you’ve followed Captain Marvel’s, especially as some of them take place right here in England. You can rely on me to fight evil wherever it exists. All for now, your new and true friend – Marvelman.’

Thank you, Marvelman. I’m certain that the boys and girls will be just itching to read your first comic which will be appearing shortly.

Well, that’s all for this week chums, except to say have a good Christmas and mind how you go with the pudding.

Your sincere pal,

Captain Marvel

Dear Boys and Girls,

The news that Captain Marvel Jr. is retiring and that his place is being filled by a new hero, namely YOUNG MARVELMAN, has spread far and wide. I’ve had letters from all over the British Isles, from Lands End to John o’ Groats. Outside this land of ours, letters have arrived from as far away as Malta, the Persian Gulf, and even India. Overnight my mail has swollen to gigantic proportions.All of you are anxious to learn more about your new hero. What does he look like? How is he dressed? Does he use the same magic word as Captain Marvel Jr.? How old is he? Is he English or American? Can he fly? Is he strong? Will the new adventures be on sale every week? What is the new Club going to be like?

STOP! Steady on. Allow me to collect my thoughts. One at a time please.

Now then, let me see if I can possibly answer your enquiries. What does he look like? Well in the first place he’s very much like Freddy Freeman, about the same build and age, and just as loyal to his job. He works as a telegraph boy.

Like his predecessor his aim is to fight evil wherever it exists and to help those that are poor and weak. As soon as he encounters some wrongdoer he utters a magic word – No, not Captain Marvel, but another word just as powerful – that unfortunately must remain a secret until the comic is published. In an instant he is changed to the YOUNG MARVELMAN, and woe betide any criminal who happens to cross his path. YOUNG MARVELMAN, his steely blue eyes flashing, muscles rippling like a panther, is a match for any of them.

The Mightiest Boy in the Universe has fair hair. His build and strength are enormous. He fits his skin tight red costume, as if he were poured into it. Unlike our old hero, he doesn’t wear a cape, and on his chest is the insignia YM, which stand for, you guessed it, YOUNG MARVELMAN. He is able to fly like a bird faster than sound, and he also has the power to go forward or backward in time.

His strength and remarkable brain power are the envy of every criminal in the world, who are constantly trying to find a way to outwit him, and some come very close to doing it.

But I mustn’t tell you too much about this Universal Crime fighter, as you must read all about him yourself in the new weekly comic. Only then will you discover what a Pal you have in YOUNG MARVELMAN.

Your Sincere Friend,

The Editor

There were also fan clubs for both original characters run by the Millers, which were apparently hugely successful – Mick Anglo mentions a figure of six thousand members at one point – and these were simply transferred over automatically to their respective new characters on the 31st of January 1954.

There was no hitch, no hiatus. The new titles were greeted with increased sales, and letters poured in from enthusiastic kids demanding a Marvelman Club.

And that, it seemed, was that. Marvelman had successfully launched from the ashes of Captain Marvel, without a hiccup. Sales were brisk, perhaps even better than before and, unbelievable as it may seem in these considerably more cynical times, the comic-buying public accepted the changeover without question.

To Be Continued…

(You can find larger versions of all the images in this post here.)

Dear Boys and Girls,

Dear Boys and Girls,

Are there are no details to Mick Angelo’s ownership/contract for Marvel Man? The US tradition is the publisher owning it lock stock and barrel due to work for hire. Especially in the 1950’s. I’d be curious if there was any splitting of profits from the character.

Mannnn this is great stuff — really nice work. I really liked the link to the Gladiator story as well. I’m pretty sure Jerry didn’t actually read the novel — but he knew all about it (there was a big review of it in his favorite magazine). When you get to the Marvel/Gaiman deal, let me know and I’ll put you in touch with the guy who suggested it. It’s a crazy story.

Jamie Coville: It’s an interesting question. I’ve certainly never seen any contract, but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t one. I’ve seen a number of people claim that without proof that Anglo signed over the right for Marvelman to L Miller & Son, that it obviously means that he has always owned the rights himself. Which is obvious nonsense. Just like in the USA, the publisher was also the owner of the rights. It might not have been right, but that’s not the issue. It’s the way it was, and I’ve never seen anything to contradict that.

Brad Ricca: Thanks. I have duly written to you. Your forthcoming book on Siegel & Shuster look very interesting, I have to say.

Enjoying this series a lot.

If it’s revised for publication you might want to look at the first paragraph – 1884 wasn’t Ally Sloper’s first appearance as a character and the Rainbow began in 1914. In the 1950s when Marvelman was being published it’s not the case that UK comics publishing was dominated by Amalgamated/Fleetway and D C Thomson. Hulton Press, with the Eagle stable, was as important as either of them, and Beaverbrook (TV Comic, TV Express) was also a big player.

(It’s also a matter of opinion of course, but personally I wouldn’t agree that British children’s comics “only found their place” with the arrival of the Dandy and the Beano, important as that was. They were launched into a well established marketplace).

I appreciate it’s not your intention to suggest otherwise, but it’s perhaps worth making clear that American reprints were only a small element in UK comics publishing, and that the Marvelman titles never seriously challenged the big players in UK comics, either in sales or popularity. L Miller and Son (like Alan Class a few years later) were tiny outfits operating very much at the downmarket end of comics publishing. Marvelman was a rare example of UK superhero comics and retrospectively that risks suggesting that it was more important than it was. The fact that superhero comics were such a niche genre in the UK is itself quite interesting. Had that not been the case L Miller and Son wouldn’t have been able to get the toehold they did.

Silly true story – I had asthma as a child and at the age of 4 or 5 (1957-8) I’d be off school one afternoon a week to visit a chest clinic. In the room it took place there was a table which appeared, to my child’s gaze, to be groaning under the weight of children’s annuals. And the one I particularly wanted to look at was a Marvelman one. But every week just as I started to move towards it my mother would arrive to take me home. It seems to me now that that serves as something of a metaphor for many aspects of the Marvelman saga.

I’m writing this on my phone, and sadly I haven’t had the opportunity to really read this article yet, but a quick skim brought a name to my eyes, Judge Learned Hand. That guy was quite the character himself and it’s only right he, of all judges, would be the judge for the Captain Marvel/Shazam case.

While it does seem strange that there was so little communication between Fawcett and Miller, the fact that Capitao Marvel was published in new locally-generated material as late as 1968 in Brazil (even teaming up with the Human Torch in one 1964 story!) suggests that they weren’t all that closely observant of their overseas licensees.

Dave Hartley: Yes, you are of course right about Ally Sloper having been around before Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday first appeared. And, yes, The Rainbow ran from 1914, not 1912. Thanks for pointing these out. And I also generally concur with what you’re saying about the marketplace at the time The Beano and The Dandy were launched, but I was trying for a general overview of the history of British comics, rather than a specific snapshot of the times, so I had to try not to go into too much detail. Actually, there’s hardly any part of the early history of Marvelman and his times that I couldn’t have delved more deeply into, but I had to try to draw the line somewhere, and to keep it all reasonably relevant. The same explanation applies to the place of American reprints in the UK comics marketplace. It is worth noting that they were only a small part of the market, though, something I shall attempt to introduce into any subsequent telling of this story!

And, again, yes, Miller & Son were, as you say, towards the lower end of things, as indeed was Mick Anglo. I’ve a lovely quote in the next piece from Don Lawrence about how working for Anglo was as low as you could get! The thing is, there has been a huge amount of revisionism about Anglo’s place in the scheme of things, particularly if you read some of the American press, who have attempted to fill their lack of information with, essentially, lies. When he died, I wrote an obituary of him for the Forbidden Planet blog, where I said,

And thanks for the story about not getting to read those MM annuals when you were young. I was 22 when the first issue of Warrior came out, and couldn’t wait to find out what happened next. I remember waiting about a year for Moore’s last issue of Miracleman to come out, a few years later, by which time I was 30. Neil Gaiman’s last issue came out in 1993, just before I turned 34. I’m now 53, and waiting to see what happens next. It seems I have spent pretty much my entire adult life waiting to for the next issue of some version or other of MM to appear.

Chris Hero : Judge Learned Hand turns up quite a bit in the previous piece to this one.

Devlin Thompson: Later on, I’ll have different opinion on what might have happened between Miller and Fawcett, with at least some evidence to back it up.

I really like your comment on secret identities and how it relates to the dual identities of many Americans. I’d be interested to read more thoughts on the subject and maybe on other aspects of the Superhero that are informed by the creator’s home country. It seems Marvelman could be the perfect case study of this (being essentially adapted from an American character). Were there other aspects changed or abandoned in his earliest appearances that you would say made him (for lack of better terminology) more British, or at least less American?

This is fascinating stuff. I bought my first Marvelman comic as a child in England in the 1950s (yes, I’m that old), and loved the artwork. The later incarnations were less attractive; I did follow his adventures, but disliked the new harsher realism. Still, I wish they’d sort out the legal stuff, and publish more of this great hero.

Comments are closed.