[Previous chapters: Introduction, 1 – Prehistory, 2 – Marvelman Rises, 3 – Marvelman Falls, 4 – Intermission: 1963 to 1982]

Born in Goole in Yorkshire on the 4th February 1951, by 1982 Derek ‘Dez’ Skinn already had a long and successful history working in British comics.

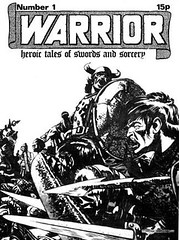

With a publishing company and a name in place, the next thing was to find content for the magazine. Warrior was going to be an anthology, a format that had always done well in the UK market, as opposed to the single-story-per-issue format popular in the US, although it would be monthly, unlike the weekly British comics. Skinn had seen the sort of material that was popular for the comics companies he had worked for, particularly at Marvel UK, so knew what sorts of strips he wanted for Warrior. There had always been a dark streak in British comics, and Skinn was happy to allow some of the strips in Warrior to reflect that. He did, however, feel that he should include a superhero strip, to appeal to the American market, as much as anything else. Skinn’s plan for contributors was fairly radical for Britain at the time: He was going to offer less money up front (either a half or two-thirds of the going rate, depending on who you listen to), but was only buying first printing rights from them, and they would retain ownership of their creations – rather than surrender all the rights, as was usually the case with comics publishers – and would therefore be able to sell them to other markets abroad, as well as in collected reprint editions, and actually earn good money from doing so. To facilitate this, Skinn encouraged his writers to write story arcs that would run over the course of a year, which could subsequently be collected in book form. Skinn was also intending to set himself up as an agent for this work, to try to sell it abroad, primarily to the lucrative American market, as well as to the thriving European markets.

By 1981 Dez Skinn had been working in British comics for over ten years, and had made it all the way to the top, so he was not short on talented potential contributors for his magazine. He already had his old friend Steve Moore on board as his main writer, along with Steve Parkhouse, who was both writer and artist, and Paul Neary would also write and illustrate a strip. Other artists on Warrior would include Brian Bolland, John Bolton, Alan Davis, Steve Dillon, Dave Gibbons, Garry Leach, and David Lloyd, all of whom made significant contributions to the magazine, and most of whom would go on to become huge names in the comics industry, both in Britain and in America.

The strips in Sounds were Roscoe Moscow: Who Killed Rock’n’Roll, which ran for sixty episodes from 31 March 1979 until 28 June 1980, and The Stars My Degradation, which ran for one hundred episodes from 12 July 1980 until 19 March 1983. Moore drew both strips, and wrote most of them, with Steve Moore coming in as writer for the latter part of The Stars My Degradation. He realised, however, that he was not cut out for a career as an illustrator, so began to concentrate solely on his writing.

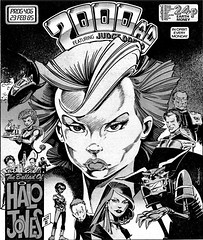

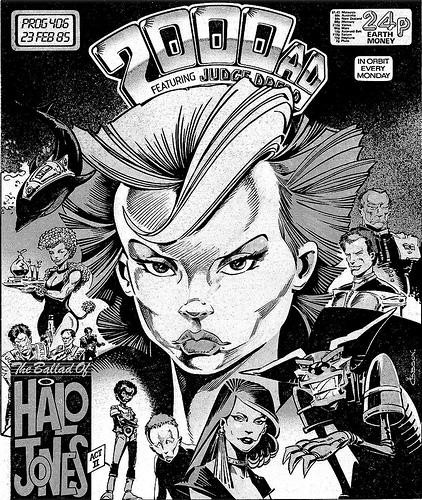

In 1981 Moore started getting work published in IPC’s weekly comic 2000 AD. Although 2000 AD had only been around for three years at the time, it was easily the most important thing to happen to British comics for many years, and would provide a launching pad for the careers of any number of British comics people, both writers and artists. Moore started submitting short pieces, Future Shocks or Time Twisters, as they were called. These were often only two or three pages long, giving him an ideal opportunity to perfect his craft. More work followed, with Moore contributing short one-off pieces to the newly revamped Eagle, as well as to Marvel UK’s Doctor Who Weekly. Later on, he would be offered the opportunity to do longer work at both IPC and Marvel UK. For 2000 AD he would eventually write Skizz in 1983 (effectively written to cash-in on the huge media frenzy surrounding the forthcoming ET movie, but only similar to it if you imagine that, instead of being marooned in a Disney-perfect, Hollywoodesque America, the extra-terrestrial crash-lands his ship in a dour and depressive Birmingham, deep in the throes of the worst excesses of Thatcherism),

Skinn had decided that, if he was going to include a superhero strip in Warrior, he wanted to revive an old one, rather than try to create a new one. He’d been successful in revitalising the Captain Britain character in Hulk Comic whilst at Marvel UK, and there was really only one other British superhero that had ever had any success, so he decided that he’d bring back a character that hadn’t been seen on the shelves since 1963. That character was Marvelman.

This is wrong on several fronts, of course: the Millers didn’t go bust, in 1963 or at any other time, and even if they had, it is unlikely that the Official Receiver would have held onto the property, intellectual or otherwise, of a bankrupt company for close to twenty years, as it would have been sold off at the time to pay off any creditors, meaning there would have been nothing there for Skinn to buy in 1982. On top of which, I don’t think there is a single instance in print of Skinn being quoted as saying this at the time, or of subsequently verifying that it was true. Which is not to say that he might not have said it, or something similar to it, and indeed there is some hint towards this in later communication between Skinn and the legal representatives of Marvel UK, where he says, ‘Considerable expense was involved in securing and relaunching the 1950s and 1960s registered property,’ a particular statement that is actually backed up by Skinn himself, elsewhere.

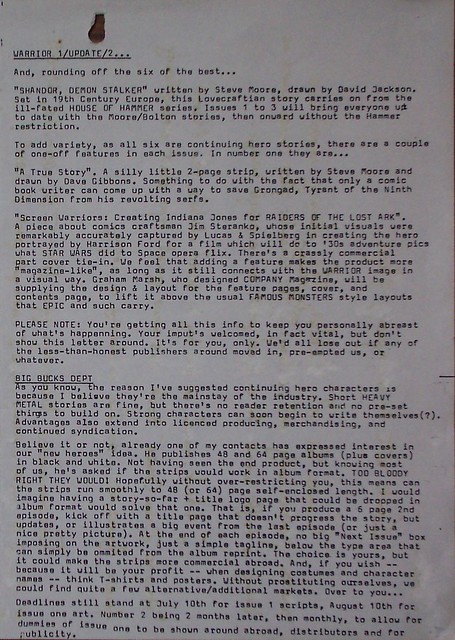

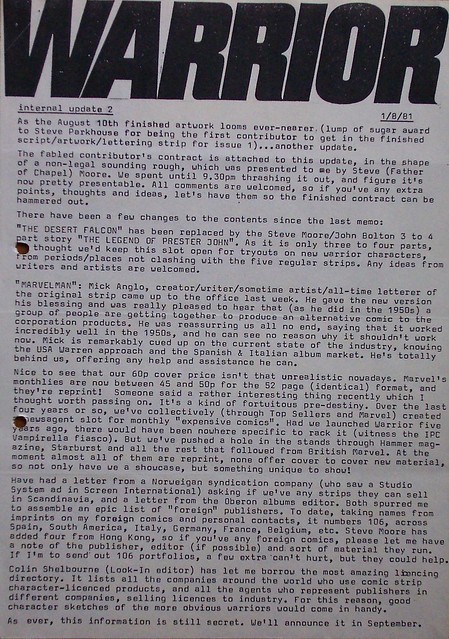

When he was setting up Warrior, and actually had some people on board, he sent out a few internal memos [which are all to be found at the bottom of this post]. The first of these, dated the 24th of June, 1981, says, in referring to Marvelman, that ‘we’ve almost got the rights tied up…’ In the second memo, dated the 1st of August, 1981, he says:

Marvelman: Mick Anglo, creator/writer/sometime artist/all-time letterer of the original strip came up to the office last week. He gave the new version his blessing and was really pleased to hear that (as he did in the 1950s) a group of people are getting together to produce an alternative comic to the corporation products. He was reassuring us all no end, saying that it worked incredibly well in the 1950s, and he can see no reason why it shouldn’t work now. Mick is remarkably cued up on the current state of the industry, knowing the USA Warren approach and the Spanish & Italian album market. He’s totally behind us, offering any help or assistance he can.

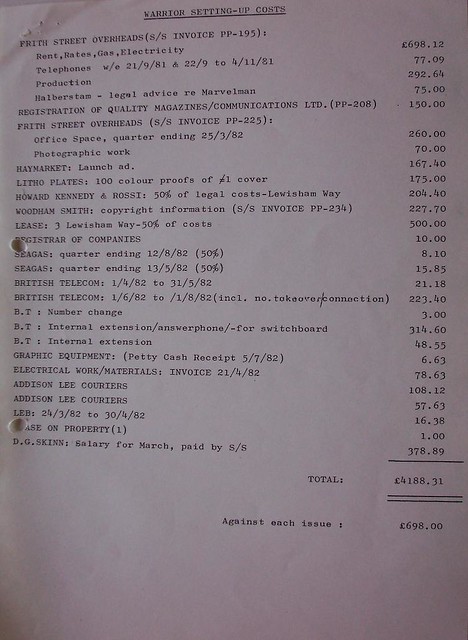

Another internal document called Warrior Setting-up Costs – undated, but obviously from around the same time period – listed, amongst other costs,

Halberstam – Legal advice re Marvelman: £75.00

Woodham Smith – copyright information: £227.70

Obviously there were other issues relating to copyright at Warrior, besides those relating to Marvelman. After all, they were launching a magazine with all sorts of new rights being offered, and they would have needed legal advice for these, too. None the less, it’s still interesting to see these figures, and to speculate on what they might mean. After all, Woodham Smith, a now-defunct London legal firm, specialised in the field of Intellectual Property, so it seems likely that at least some of their advice had to be in relation to Marvelman.

Other elements of this version of events are actually close to the truth: L Miller and Co hadn’t gone bankrupt, but the company nevertheless no longer existed, so couldn’t own the copyright to Marvelman, and there didn’t seem to be any other clear owner, so, although it wasn’t being held by the Official Receiver, it was arguable that the rights were available for whoever wished to take them. Dez Skinn gave his version of events to George Khoury in Kimota! in 2001:

I knew the character was in the public domain, not because of the usual time lag after the end of the strip like when Stan [Lee] took Daredevil after the Lev Gleason run finished or anything like that. It was simply because the company had gone out of business and no longer owned anything. There wasn’t a copyright holder. It wasn’t a person; it was packaged – work-made-for-hire by L Miller and Son Limited through Mick Anglo Studios. Mick couldn’t claim copyright really, because he did the lettering and he gave the scripts – which were often photocopies of Captain Marvel comics – to the artist and said ‘Make this more English! Change the costume to Marvelman instead of Captain Marvel.’ The reason it felt close to Captain Marvel was because they were Captain Marvel stories.

Yeah, so nobody really owned it. There was no copyright holder.

Dez Skinn’s plan all along for Marvelman included republishing some of the old adventures from the 1950s as flashbacks, so he got in touch with Denis Gifford, the great British comics historian, to see what he could tell him about the status of Marvelman. Gifford directed him to Mick Anglo – who Skinn already knew of old – who Dez then talked to, to tell him that he wanted to use his old work, and to pay him for it. Anglo seemed to be the only person who still had an interest in the rights to the Marvelman, as shown by his copyright notice in Nostalgia: Spotlight on the Fifties in 1977, but this doesn’t seem to have come up when he talked to Dez Skinn. Both of them have referred to their discussion at various times. Talking to Khoury in Kimota!, Skinn said,

I got in touch with Mick Anglo. I met with Mick and I said, ‘Look, I know you don’t own it but if we bring the character back and it’s popular… You have thousands of pages of material’ […] because it would be nice for an old guy like Mick Anglo if we could reprint stuff that he was involved in and pay him.

And this is Mick Anglo, again talking to George Khoury in Kimota!,

[Dez Skinn] contacted me and he wanted to revive [Marvelman] and I said go ahead and do what you like, as far as I was concerned.

Despite the number of times that Anglo could have stated that he thought he owned the rights to Marvelman, including the time that Skinn went to talk to him in 1982 about republishing it, or when George Khoury interviewed him in 2001 for Kimota!, I still haven’t been able to find an account of him having actually said so in plain unvarnished English, although he does claim to have created the character in a few different places, a claim which itself could be open to question. If anything, he tended to distance himself from the character, and from his history with it. Could it be that he had lost interest in it, only five years after publishing a book containing a page of art with a copyright notice newly added to it? Or that he believed that, despite his copyright notice in 1977, he actually had no rights to the character that would stand up to scrutiny? Or simply that he thought that it was hardly worth bothering over, as more comics magazines folded after a few issues than ever survived?

One thing I’m pretty sure about is that he wouldn’t have stood for Dez Skinn using Marvelman against his wishes, and that if he felt he owned the character, he would have made this clear. Mick Anglo had been the boss of his own studio – where he reputedly once threw one of his artists down the stairs when he was annoyed at him – and had been a boxer and a soldier, to boot. In 1982, even if he was sixty-six years old, he was unlikely to allow himself to be pushed around. It simply doesn’t make sense to me that he opposed Skinn, or even that he had any interest in Marvelman at that point, as he would definitely have made this known, so the only conclusion I can draw is that he had no interest in Marvelman in 1982, and wasn’t claiming it as his own at that time.

‘Dream of Flying’ written by Alan Moore, drawn by Garry Leach. Set in 1981, England. The first episode builds up to re-introducing a hero who represents the (inevitable) super-hero content. And (gasp, shock) it turns out to be none other than Denis Gifford’s old pal, Marvelman. We’ve just about got the rights tied up…

Of course, it may simply have been that talk of the character was in the air, without anyone deliberately focusing on it, and that this caused both Moore and Skinn to think of it in terms of actually making a go of it, and that their apparently both fixing on it separately may simply have been both of them unconsciously responding to a raised interest in it in general. One way or the other, though, it’s unlikely that Moore’s announcing he wished to write Marvelman was made without him knowing that the possibility of that happening actually existed, it seems to me.

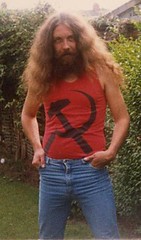

The supposition that Dez Skinn didn’t know of Alan Moore at the time, as he has claimed, is also open to scrutiny. Although he was new to comics writing, by 1981 he had already made enough of a name for himself for David Lloyd to include him in the list of ‘Five of the most respected and reputable strip writers in British comics’ that he sent his questions to, and David Lloyd would also go on to suggest Moore as the writer for the strip that would eventually end up as V for Vendetta. Meanwhile, Steve Moore, originally intended as Skinn’s anchor writer for Warrior, surely couldn’t have discussed the possibility of using Axel Pressbutton as a character with Skinn without mentioning the artist who had drawn the various strips he had appeared in. And, if Skinn was on the lookout for good British talent for his magazine, and particularly since he was very much involved with the British comics industry, how could he not have noticed this interesting new writer, although everybody else had? If nothing else, there just weren’t that many British comics, and it is likely that Skinn would have been familiar with all of them, and who was doing what. On the other hand, if Skinn had met Alan Moore, he’d definitely have remembered him, as there’s no way you would forget him. It may all just be Skinn wishing to play down how things happened at the time, for whatever reason.

In 1981, Dez Skinn had first offered the Marvelman strip to Steve Parkhouse, who wasn’t interested in it, and then to Steve Moore, who also passed on it, but who supposedly said that his friend Alan was dead keen to do it. Skinn was cautious about offering the strip to an unknown writer, but agreed to allow Moore to submit a proposal for the strip, initially unpaid, so that Skinn could see what he was intending to do with it, with the proviso that he wanted to use the 1950s material if possible, whether it be as a dream, a flashback, a what-if, or something else. Moore’s extremely detailed five-thousand-word proposal was a revelation, and Skinn knew he had found the writer he needed to revive Marvelman. Moore’s pitch is reprinted in its entirety in George Khoury’s Kimota! , so I’m only going to quote a few short passages from it here.

Briefly, what I’d like to do with Marvelman runs as follows… I’d like to make some very radical changes in the basic conceit to bring what was basically a silly-arsed strip into line with the nineteen eighties. At the same time, there are some elements of Marvelman which are obviously worth hanging onto… otherwise we wouldn’t be reviving it. What are these elements? Well, firstly there’s the obvious fact of his being a superhero. […] I know this’ll sound very pompous and ambitious but what I really want to attempt here is not just the definitive Marvelman, but the definitive superhero strip as well.

The second important element is that Marvelman is an old fifties superhero, so there’s a strong element of nostalgia. Nostalgia, if handled wrong, can prove to be nothing better than sloppy and mawkish crap. In my opinion, the central appeal of nostalgia is that all this stuff in the past has gone. It’s finished. We’ll never see it again… and this is where the incredible poignance of nostalgia really comes from. So, without deviating in fact from the naive and simplistic Marvelman of the fifties, I want to transplant it into a cruel and cynical eighties. The resultant tension will hopefully provide a real change and poignance.

The third point relates to both the ones above. The superhero genre is an offshoot of science fiction (amongst other things), and good sci-fi usually runs according to certain established laws. To my mind the most important of these is that the fantasy in any given story should stem from one divergence from reality. […] If my Marvelman is going to fit logically into a gritty and realistic nineteen eighties then the character should at least have some pretence of credibility. Thus all the fantasy in the strip stems from one point… the crashing of an alien spacecraft in 1948. Everything else follows on from that.

So basically what I’m after is a spectacular nineteen fifties superhero in a blue costume who says a magic word and was given his power by a wise old wizard and who now operates in the nineteen eighties and who is totally scientifically credible!!!! Sounds tough, huh?

Towards the end of the pitch Moore says,

In the event of us not getting the rights to Marvelman then obviously I’ll have to rework all these notes. But possibly we could still do something featuring a pastiche character called Miracle Man who transformed himself with a cry of ‘Raelcun!’ or summat.

Talking about preparing to write Marvelman when interviewed by Eddie Stachelski in issue #5 of Fantasy Express in 1983, Moore said,

When I researched Marvelman, I tried to get right back to the roots of the superhuman and sort out exactly what made the idea tick. I read obvious things like the Greek and Norse legends again, I read a lot of science fiction stories that touched upon the superhero theme… things like [Olaf] Stapleton’s Odd John and Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. I even read a few comics.

There were other influences on Moore’s Marvelman, too. When I interviewed him in 20112, I asked him about the influence Robert Mayer’s Superfolks had on the character of Marvelman:

Well, I have read Superfolks. […] But it was by no means the only influence, or even a major influence upon me output. […] I can’t even remember when I read it. It would probably have been before I wrote Marvelman, and it would have had the same kind of influence upon me as the much earlier […] Brian Patten’s poem, ‘Where Are You Now, Batman?,’ which was in the 1960s Penguin Mersey Poets collection, The Mersey Sound, and that, which had an elegiac tone to it, which was talking about these former heroes in straitened circumstances, looking back to better days in the past, that had an influence. I’d still say that Harvey Kurtzman’s ‘Superduperman’ probably had the preliminary influence, but I do remember Superfolks and finding some bits of it in that same sort of vein. I also remember reading Joseph Torchia’s The Kryptonite Kid around that time. I found that quite moving. […] Like I say, it probably was one of a number of influences that may have had some influence upon the elegiac quality of Marvelman. I can’t remember any specific […] things that I might have been influenced by, other than that general post-modern elegiac feel.

In Lance Parkin’s The Pocket Essential Alan Moore (Pocket Essentials, 2001) Moore is quoted as saying,

[Superfolks was] a big influence Marvelman. By the time I did the last Superman stories I’d forgotten the Mayer book, although I may have it subconsciously in my mind, but it was certainly influential on Marvelman and the idea of placing superheroes in hard times and in a browbeaten real world.

According to Lance Parkin, the quote was actually taken from a handwritten annotation to the proof by Moore himself, after he read a draft of the book in manuscript form, one of only three such annotations, so at the time he certainly must have felt strongly that he wanted to acknowledge the debt Marvelman owed to Robert Mayer’s book.

[There’s more information about the influence of Robert Mayer’s Superfolks on Moore’s writing in these two articles, if you’re interested: Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 1: The Case for the Prosecution and Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 2: The Case for the Defence.]

Dez Skinn had originally offered the artwork on Marvelman to Dave Gibbons, who was too busy to take it on, and then considered offering it to Brian Bolland, but decided that, whereas Bolland’s work was extremely good, he was also very slow. Eventually, apparently on David Lloyd’s recommendation, Skinn asked Garry Leach, an artist unknown to him at the time, but who would also eventually end up as Warrior’s art director, a job he described as being much more glamorous in its title than its actuality. Leach had been working as an artist for 2000 AD since 1978, and had previously collaborated with Alan Moore on the short story They Sweep the Spaceways in issue #219 in July 1981, at the same time that Dez Skinn was starting to put his plans for Warrior in order.

The pieces were in place, and the stage was set for Marvelman to once again take his place in the forefront of British comics.

To Be Continued…

Some of the best online comics journalism I’ve ever read. Now I’m disappointed when I check the site and there isn’t a new one.

(though Heidi still hits home runs that leave me nodding my head in agreement)

The description of Moore being among “Five of the most respected and reputable strip writers in British comics” is a little hyperbolous. Aside from his work for Sounds and the pseudonymous and localised Maxwell the Magic Cat, by May 1981 Moore’s published work consisted of a handful of back up stories for Doctor Who Weekly about half a dozen one-off strips for 2000AD. These aren’t negligible by any means, though none them are suggestive of a world-shattering talent emerging just yet, and it’s difficult to imagine that he had much of a reputation or respect outside the immediate circle of writers, artists and editors with whom he had worked to that point. David Lloyd had illustrated most of his Doctor Who work, of course, so it could just be a case of bigging up a talented newcomer to make him sound more impressive than he actually was – at that time at least.

Very timely.

To follow up from Kate Halprin’s message (and apologise if this is a bit pedantic considering how great the piece is in general, but its worth mentioning) you say.

“Eventually, apparently on David Lloyd’s recommendation, Skinn asked Garry Leach, an artist unknown to him at the time…”

Yet by 1981 Garry Leach’s art had appeared relatively frequently in 2000ad (and I’m sure elsewhere but I can’t back that up) compared to Alan Moore and in more visible strips too, Dredd, Dan Dare, VCs as well as one off’s. If its conceivable that he didn’t know Garry Leach (at a later date too I think) its conceivable he wouldn’t have picked up on Alan Moore’s name either?

In the end, I can only go on the best information I have, hence my using words like ‘apparently.’ The whole issue of whether or not Dez Skinn had heard of either Moore or Leach is an interesting one, but he simply may not not remember. The same thing applies to the issue of whether Moore could be considered one of the ‘Five of the most respected and reputable strip writers in British comics’ or not. The fact that this appeared in what was essentially a trade magazine for comics professionals is interesting, though, as surely it’d be difficult to pull the wool over their eyes. So perhaps he was seen as being hot stuff inside the industry from early on…?

I also think that the timing and the “trade insider” element at play is something to keep in mind. From an American comics perspective Skinn had a very savvy plan offering a much lower page rate, an anthology format, and the potential serving as an agent in selling collected works in other formats and markets. If you consider the timing of this, its a very smart idea for collecting new talent with the lowest capital and taking advantage the changing distribution network of comics fandom and the international scene.

So I wonder how much gossipy or inside knowledge Skinn and Anglo might’ve had about the copyright scene at that time and how it might’ve played into their own decisions regarding the character. The SUPERMAN creator issues since the time of the movie, the movement of “Creator Rights” it instilled, questions of Jack Kirby’s role at Marvel and the new alternative press scene and fan convention circuit that was starting to develop meant these guys were thinking about and re-inventing the system. And, through things like Marvel UK, talking to one another despite that ocean in between.

I wonder if Anglo’s decision to show that copyright on a page in 1977 might have been a bold idea at a time when creator rights seemed important and valuable and Marvelman’s original publisher wasn’t around to refute it. It might not have seemed worth it to him five years later when someone else was willing to pay him again for work he did decades before.

Was Skinn’s decision about proceeding with the project without a clear purchase of the copyright equally bullish? Did he think that maybe, just maybe, by involving the creators, both past and contemporary, in a rerelease of the work under a contract that implied long-term creator control, he could skirt the ownership issue?

A bold approach to the idea and very much in keeping with the art of the time.

When considering whether Dez could really have been unfamiliar with Moore’s name, bear in mind that much of Moore’s early work, including the Frantic piece he did for Dez and the Sounds strips where Pressbutton originated, were produced under pseudonyms.

Comments are closed.