[Previous chapters: Introduction, 1 – Prehistory, 2 – Marvelman Rises, 3 – Marvelman Falls, 4 – Intermission: 1963 to 1982, 5 – Prologue to Warrior, 6 – A Warrior is Born, 7 – A Warrior Stumbles]

By 1984, things were starting to fall apart at Warrior.

Alan Moore’s Marvelman is threatened by Dez Skinn’s Big Ben

I had withheld an episode of Marvelman from Warrior because I hadn’t been paid for the previous one. I knew Warrior had serious financial problems but I simply wasn’t willing to work for free. In the time I withheld the episode Alan and Dez’s ‘fragmenting’ relationship hit a terminal crisis. (I’m not going to go into detail but I was in the middle, heard both sides and realised a reconciliation was impossible).

There was no heroic melodrama or valiant struggle for creators’ rights, just practical business decisions muddied by ego and legacy building. Dez had invested heavily in Warrior and was struggling to keep it alive. To add to his financial woes, DC started to poach his contributors. Pros, simply climbing the ladder of professional advancement and financial security, or rats deserting a sinking ship – the ship that had, in part, made their advancement possible?

Just look at the published chronology and factor in the delay of production time to create a timeline. Alan Moore got his break with DC in 1983. His last Captain Britain was June 1984, the last Marvelman August 1984. In actual fact I had finished my final Marvelman months earlier than his last Captain Britain but held it back because I hadn’t been paid for the previous episode. As creator Alan could get ahead on Marvelman scripts whereas Captain Britain was usually a rush after waiting for scripts (and page count) approval.

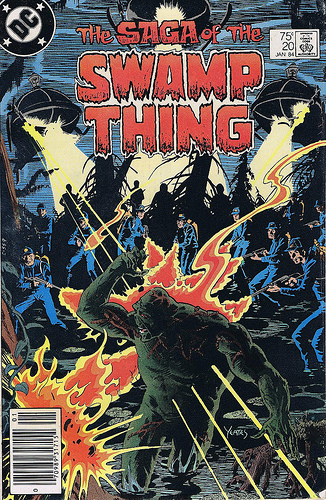

Details aside, Alan clearly quit both Captain Britain and Marvelman at virtually the same time but claims external, unconnected reasons for both. Isn’t it simpler to accept that with Swamp Thing and new offers from DC – which were far better paid – the volume of work increased to a point where choices had to be made. I know I, amongst many other creators, was hoping for a call from DC.

It’s generally thought that the two Alans fell out at this time over their work together, or over one or the other refusing to work on one of their mutual projects, or over Moore refusing permission for Marvel to publish his work on Captain Britain in the US, but that wasn’t until a bit later on, and they were certainly still talking after both strips finished, according to Davis,

I decided to write Captain Britain myself after Alan quit but my plan was derailed just a few months later when I was offered an Aquaman miniseries by DC. During a conversation with Alan about the reliability and practicalities of working for DC, especially their imposing ‘work for hire’ document, he asked me to consider Jamie Delano as a writer on Captain Britain – since I would quickly hit deadline problems with the addition of DC work.

I agreed. Alan later came over to my house with Jamie, in part to introduce Jamie but also to see the last episode of Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Black Stuff which he had missed – this was in the early days of VHS and Alan may not have had a recorder. Jamie’s first Captain Britain appeared in January 1985.

The Marvelman strip had run in seventeen of those twenty-one issues, amounting to 112 pages, drawn by either Garry Leach or Alan Davis; there was a further ten-page story in the Warrior Summer Special 1982, drawn by Steve Dillon and Paul Neary, as well as Alan Davis; and there had been four other Marvelman related stories – the two-part Warpsmith story in #9 and #10, drawn by Garry Leach, a five-page Young Marvelman story in issue #12, illustrated by John Ridgway, and a twelve-page Marvelman Family story called The Red King Syndrome in issue #17, also illustrated by Ridgway. All these had been written by Moore. In total, Marvelman and related stories had run for 154 pages, from March 1982 until August 1984, a period of just two-and-a-half years. In that time Moore had gone from being virtually unknown to the most famous comics writer in Britain, and probably in the world, a position he undoubtedly holds to this day.

Warrior itself continued on, but with its most popular strip gone, its days were numbered. Part of the problem was inherent in the way the magazine was set up – creators’ rights had a downside, as well as an upside, certainly from the publisher’s point of view. If the creators owned their strips it meant that, should they be late with their work, or simply cease doing it altogether, there was really nothing the publisher could do but carry on without them. And if two creators owned a property between them, and fell out, then there was little chance of retrieving the situation if they didn’t make up their differences. There was certainly no mechanism for removing the creators and replacing them with other writers and artists, as could be done if the titles were owned by the publishers.

There were also the ongoing financial problems. Despite its huge critical acclaim, Warrior had never been a profitable venture, and had turned into a black hole that consumed all the money that Dez Skinn threw into it, without any appreciable difference to the situation. With some of his best features gone or missing in action, Skinn began to use reprints and outsourced European material, further adding to the slide in quality, and to the disquiet of its readers. Warrior was on a slippery downward spiral from which it simply could not recover. Skinn told me,

Like Warren’s magazines, 2000 AD and the rest, Warrior lost some contributors after a few years. That’s inevitable. You showcase new talent and bigger players lure them away. It’s the downside of being a small publisher. But Warrior and my shops (I had opened a second one in King’s Road, Chelsea) needed each other to survive. Each promoted the other and as it was all Quality, the money went into the same bank account. Profit wasn’t the issue to me, I enjoyed what we were doing and just wanted it to continue.

But any big publisher would have cancelled Warrior when the issue #1 final sales figures came in. I just cancelled the Summer Special! The original shop was ticking over, I had very low overheads, so it worked. I couldn’t afford a car, a nice home or any luxuries but I only cared about my all-consuming passion, attempting to improve an industry I’d dedicated my life to.

But then the Quality shop manager dropped the biggest clanger imaginable. I’d been in a contra arrangement with comics’ distributor Titan, where we supplied them with Warrior and they supplied our shop with US comics. It worked fine until one Saturday Titan boss Mike Lake phoned me and said, ‘I’m really sorry but there’s been an accounts mix-up with the contra. You actually owe us £25,000 more than the Warriors you’ve supplied.’

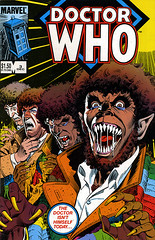

When I investigated, I found the shop was grossly overstocked. As an example, to take the Doctor Who

Baxter reprints then being published, which were up to about issue #10 at that time. I said to the manager, ‘How many copies do we order?’ He said, ‘A hundred.’ I said, ‘Do you know how many we sell on average – TEN.’ We’d ninety per cent leftovers in the back room and he hadn’t even noticed. Multiply that by the amount of titles he was ordering each month through sheer guesswork and you soon get to that £25,000 imbalance.

So it was a combination of things, Titan accounts mismanagement, Quality ordering mismanagement and me not keeping a closer eye on everything. Suddenly I was totally out of money and deeply in debt.

This was the time that Marvel UK chose to write to Quality Communications, via their lawyers, to express their disquiet about Marvelman. The following exchange of letters between Marvel UK’s lawyers and Dez Skinn was printed in Warrior #25 and #26:

Dear Sirs,

We act for Marvel Comics Limited and Marvel Comics Group, a division of Cadence Industries Corporation of the USA.Marvel Comics Limited has since the early 1970s published and sold periodicals throughout the United Kingdom incorporating and/or bearing its corporate name and/or registered trade mark ‘Marvel’ and/or the names of the ‘Captain Marvel’ and ‘Marvel Superheroes’ characters which are themselves registered trade marks in the UK. Marvel Comics Group is the registered proprietor of the above mentioned trade marks. Our clients are and have been for many years closely associated and identified with the above characters and the registered trade marks derived from them in the eyes of the general public.

We understand that in June 1984 you published a periodical entitled ‘Marvelman’ and bearing the additional description ‘Special No. 1’. By using the name ‘Marvelman’ in connection with that periodical, you are representing that that periodical is a product of, or associated with, our clients, which is not the case. You are, thereby, wrongfully taking advantage of the substantial reputation and goodwill which our clients have established under their respective corporate and divisional names and under the names of the several ‘Marvel’ characters referred to above. You are confusing the existing and potential customers of our clients and this has caused, and is continuing to cause, damage to our clients’ business.

Therefore, unless we receive by 12 noon on Monday, 1st October your unconditional undertaking to cease using the name ‘Marvelman’ or any colourable imitation thereof (including ceasing to use that name on or in connection with your business and periodicals published by you and on all stationery and trading documents used by you) we will recommend that our clients commence High Court proceedings against you immediately thereafter claiming an injunction to restrain any such use and damages for passing off your business as that of, or associated with, the business of our clients. We are sending copies of this letter to each Director.

Yours faithfully

Jaques & Lewis

26 September 1984

Dear Mr. Watson,

I am in receipt of your letter dated 2lst inst in connection with the above mentioned fictional character who has appeared in Warrior since March 1982 and, more recently, in Marvelman Special Number 1, May 1984. I am personally well aware of the existence of both Marvel Comics and their recently re-launched publication Marvel Superheroes. In my capacity as Marvel’s editorial director several years ago, I initiated the launch of the original Marvel Superheroes. The intention of Quality Communications is meant to be complementary to other comics’ publishers by increasing the newsstand coverage for all, in a dwindling market. Our desire is not to confuse the existing and potential customers of your clients. In much the same way your client often mentions Marvelman and Warrior in their publications’ reviews and letters columns; always favourably, as a recommendation to their readers. In fact, your client recently flattered us by including the likeness of Marvelman in several of their own comic strips.When your client recently launched a new comic, Big Ben, sending us a press release to this effect, though we had been featuring a character with the same name since early 1982, we reserved our position on possible litigation, feeling it more important to retain our good working relationship.

Nevertheless, the character Marvelman, who has not been named on the cover of Warrior since issue 16, on sale January 1984, ceased appearing in the magazine in issue 21, on sale August this year.

In connection with the Marvelman Special, all Marvelman strips were updated reprints of stories which appeared in the weekly Marvelman British comic of the 1950s and 1960s with full acknowledgement being given to their creator and copyright holder, and a full royalty paid to him.

I can only repeat that both my desires, and those of Quality Communications, are not to confuse the public into believing we are associated with Marvel Comics. In fact a disclaimer appears alongside the Marvelman strip within Warrior, tearsheet attached, and the cover of the Marvelman Special boldly stated the character was back in his own comic after 20 years, long before Marvel UK commenced trading.

For the continued good will of both publishers, I would hope this matter can be settled amicably, but if you feel this reply is not satisfactory, our solicitors are Howard Kennedy, [address removed]. All correspondence should be marked for the attention of Alan Banes.

Yours faithfully,

D.G. Skinn

Managing Director

Dear Sir,

Thank you for your letter of 26 September. We note what you say but, with respect, this does not detract in any way from the request contained in our letter of 21 September.We do not know whether or not it was your intention to imply in your letter to us that you would cease using the name ‘Marvelman’ or any colourable imitation thereof but, if this was your intention, it is not immediately apparent from your letter.

For the avoidance of doubt, we propose giving you an opportunity to restate categorically in writing the undertaking requested in the final paragraph on page one of our letter of 21 September and to deliver the same to these offices by 12 noon on Wednesday, 10 October 1984.

If that unqualified undertaking is not given by you in the manner set out above, we would suggest that you refer the papers in this matter to your solicitors as we will then be taking our client’s instructions as to the further action to be taken in this matter.

Yours faithfully

Jaques & Lewis

8 October 1984

Dear Mr. Watson,

We are in receipt of your letter of October 2nd concerning our publication of the above-mentioned character.I personally must admit to a certain amount of confusion over your repeated mention to recommend High Court proceedings against us to your client, Marvel Comics.

My letter of September 26th was intended to inform you of various facts about which you may not be aware, to enable you to fully appreciate the situation before making any recommendations to your client.

To that end, I feel I must mention that the two instances you cited, ‘Captain Marvel’ and ‘Marvel Superheroes’ are not current publications, so I cannot understand your reference to confusing customers or causing damage to your client’s business. Neither can I find either to be registered trade marks.

However, we have no plans to publish any further magazines which would feature ‘Marvelman’ as part of the title, such as the ‘Marvelman Special Number One’ which you specifically named in your original letter of September 2lst. I would hope this prevents any confusion your client feels may exist.

Such confusion is not in our interest and certainly not our intention, given the trade feeling towards your client, according to various wholesalers we have spoken to.

In connection with the character ‘Marvelman’ appearing within our publication ‘Warrior’, we have been doing so for almost three years, having received no reaction whatsoever from the wholesale trade, from readers, or Marvel Comics or their representatives concerning confusion. Given Marvel’s own recommendation for our material in print several times, and their visual inclusion of Marvelman within recent publications’ storylines, we feel entirely innocent of passing off our business as that of, or connected with, your client.

Considerable expense was involved in securing and relaunching the 1950s and 1960s registered property, which has since won many awards for its originality, but until you have cleared up this matter with the copyright holders we would prefer not to resume publication.

Your client is well aware of the copyright situation concerning ‘Marvelman’, employing the same freelance creators as ourselves, but I must insist that if your client sees this as a genuine problem, the matter is resolved quickly as we cannot realistically withhold an unfinished lead feature indefinitely.

Yours faithfully,

D.G. Skinn

Publisher

29 October 1984

Dear Sirs,

We are in receipt of your letter of 8 October 1984.Once more you have failed to deal with the main point in a direct and unqualified manner. The only reasonable conclusion to be drawn therefrom, and we so do conclude, is a refusal by you to deal with the requests we have made.

Your reference to the use of the character, Marvelman, in comic strips is irrelevant.

Our clients, as you well know, are the registered proprietors of the word ‘Marvel’ in respect of the publication by them of magazines. You have published a magazine boldly entitled ‘Marvelman’ and, for the reasons we have already made clear to you, we have asked for your unqualified undertaking not to do so again. In your letter of the 8th inst., you vacillate. Whilst stating you have no plans to publish any further magazines entitled ‘Marvelman’ you go on to say you will not hold back from so publishing indefinitely.

It is quite clear that unless you give us the unqualified undertaking already requested our Clients will be obliged to seek this remedy by such proceedings as we advise them are appropriate.

We therefore finally ask for your written unqualified undertaking not to use the title ‘Marvelman’ on or in connection with any of your publications. Unless we so hear by first post on 5 November 1984, our Clients will, without further notice, proceed as appropriately advised.

Yours faithfully,

Jaques & Lewis

2 November 1984

Dear Mr. Watson,

I am in receipt of your letter dated 29th October, in which you request a reply by first post Monday November 5th. Considering the three weeks taken by you to reply to my previous letter, you must realise it is impossible for me to give you any kind of legally binding undertaking in such a short period.I can only repeat what I stated in my last letter, which you again have ignored apparently; Quality Communications Limited has no intention of producing any further magazines bearing the title Marvelman. We have no desire whatsoever to be confused with your client’s publications, the majority of which began publication after our own.

It is furthermore apparent to the majority of people working in the somewhat specialised field of comics that if anything, your client has been attempting to move into our own, older market, seemingly unsuccessfully because presumably of their lower budgets, with the short-lived ‘Daredevils’, utilising our major contributors, and now ‘Captain Britain’, reprinting material I co-created four years ago.

Finally, Marvelman was registered during the 1950s which in all sincerity I hope you have advised your client.

Yours faithfully,

D.G. Skinn

In certain ways, it suited Dez Skinn to publish these letters. It allowed him to explain away the absence of Marvelman from the pages of Warrior without having to reveal the real reasons for that absence. It gave him a very handy scapegoat for the forthcoming demise of Warrior, and there was no doubt a certain amount of cold comfort in being able to point an accusing finger at his old employers, who really were making his life very difficult. When he printed the letters originally, Skinn included the address of Jaques & Lewis, Marvel UK’s lawyers, just to make their lives a bit more difficult, which I have removed.

There are all sorts of intriguing insights to be found in, and inferences to be drawn from the letters, not least of which is where Skinn says,

Considerable expense was involved in securing and relaunching the 1950s and 1960s registered property, which has since won many awards for its originality, but until you have cleared up this matter with the copyright holders we would prefer not to resume publication.

This once again opens up the question of what exactly it was that Skinn was alleging he did to secure the rights to Marvelman, although it may just have been bluster, to try to shore up an otherwise legally ambiguous position. The same can probably be said for this statement:

In connection with the Marvelman Special, all Marvelman strips were updated reprints of stories which appeared in the weekly Marvelman British comic of the 1950s and 1960s with full acknowledgement being given to their creator and copyright holder, and a full royalty paid to him.

Here we have Skinn apparently acknowledging Mick Anglo as creator and copyright holder of Marvelman, although he later said he never believed this to be the case. And is Skinn having a little dig at Marvel UK when he says,

Such confusion is not in our interest and certainly not our intention, given the trade feeling towards your client, according to various wholesalers we have spoken to.

It’s also intriguing that the character of Captain Marvel is mentioned in the first letter as being one of the properties that Marvel felt were being infringed upon by Marvelman, as he was of course a direct copy of a different Captain Marvel.

I can’t help wondering if, much like DC suing Fawcett over Captain Marvel, part of the reason for Marvel UK’s actions could have been jealousy over the huge critical success one of their ex-employees was having with another publication, and with a character that reflected their name, at that? And if Marvel had actually taken Quality to court at that time, it’s possible that the actual ownership of Marvelman would have been settled, saving a lot of perplexity for future generations.

Cracks were starting to show in the subscription side of things as well. Subscription copies of Warrior #25 were so late going out that they were sent out with copies of #26, which had arrived by the time they were ready to post. Reasons given in a letter that accompanied those issues included the fact that copies only reached their offices at the same time as retailers got theirs, meaning they arrived in the office in the middle of the Christmas period; the labelling computer refused to work properly, leading to in excess of eight hundred envelopes being addressed by hand, and all of the staff having to turn their hand to fitting out and decorating the company’s new shop in Chelsea, Quality Art.

There’s another insight into some of the problems they were having in a letter by Benedict S. Cullum to issue #44 of Dave Langford’s long-running Ansible fanzine, published in September 1985:

I’m halfway through a subscription to Warrior and was dismayed, on returning home from college, to find I’d received no copies since Easter. I rang up Quality and learned that the Marvel/Quality action was over; that the writer involved (Alan Moore, I think) had reluctantly agreed to change the name of his Marvelman strip; that Warrior was currently being redesigned; and that the reason for this was the return of issues 25 & 26 by the wholesalers.

It seems that WH Smith wholesale love Warrior. WH Smith retail, though, don’t know where to put it, won’t take it, and leave the wholesale department to return forty thousand copies to Quality with the message that they’ll stock it, perhaps even SELL the odd copy, provided Quality change the format. It’s not a juvenile publication and with its present design cannot be marketed elsewhere on their shelves.

The last rally of the interchange between Marvel UK’s lawyers and Dez Skinn was printed in Warrior #26, cover-dated February 1985, which was to be the last issue of the magazine, so the redesign never did happen. Apparently there was no further correspondence after this point, however. Besides the legal letters in #26, there was also a bittersweet piece about how successful many of the creators had been in getting work with American comics’ publishers, and an intriguing little snippet referring to the possibility of a team-up between Marvelman and Captain Britain, although this was then ruled out in the first sentence.

Although when I originally envisaged this book, I hadn’t any intention of doing direct interviews for it, this changed when I realised that a lot of what I needed to know wasn’t already out there to be quoted, so I’d need to take a direct hand by asking the questions I needed answers to.

I’ve already quoted from interviews with Alan Moore and Alan Davis, so it seems fitting to leave the last word on the fate of Marvelman at Warrior to the magazine’s creator, publisher, and editor, Dez Skinn.

The version for public consumption was that ever-so-handy Marvel legal letter. Amusing because by me (deliberately) running their full address I know a lot of amateur lawyers wrote to them in our defence. I even heard various tales of fan boycott of Marvel titles because of their pettiness towards us. But I should have seen it coming; they actually launched a UK weekly named Big Ben, about The Thing, after we’d published a character of the same name. Sad really.

Of course this wasn’t helped by finances being at a low ebb and me being unable to pay Alan Davis on time for his previous episode. Both Alans continued to contribute to Warrior individually after Marvelman stopped so I can’t really take the fall for that one. So if it wasn’t me that they were unhappy working with, it must have been each other. I’m putting this in a logical rather than personal way, because there’s been more than enough personal feelings, assumptions and hazy memories over the decades as it is.

And, finally, on Warrior itself:

The experiment worked. Warrior showed what creatives could do, it allowed them to flex their muscles beyond the straitjacket of everybody else out there (and actively encouraged them owning their own material). No number of additional issues could have better proven the point. I was broke at the end but I survived. Job done!

Warrior was no more, and Marvelman was homeless once more. Elsewhere, though, things were waiting to happen…

To Be Continued…

Pádraig Ó Méalóid is a middle-aged Irishman. He has been fascinated with the story of Marvelman for a very long time, and has written a book about it, which is currently looking for a publisher.

I’m surprised there’s been no mention of Grant Morrison’s Marvelman pitch to Dez Skinn (and Alan Moore’s alleged reaction to it). I know it doesn’t impinge on the copyright issue directly, but it does cast some light on what was going on behind the scenes.

What’s fun about being in the audience is I don’t know any of these people personally, so I can have whatever opinion of them I like without having to worry about hurt feelings.

I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with Dez Skinn through some messages on a blog and he was really very polite and open to discussing the questions I had. He’s always struck me as a very open person about the entire Warrior time and I’m sure he’d make a great teacher.

I know we’ll never see the Moore stuff reprinted by Marvel because besides not knowing who owns the rights, there are the issues of Big Ben and the Warpsmiths being involved. I feel guilty about saying this, but I’m beginning to think it’s funny how badly this exploded on Marvel. They bought a very expensive quitclaim deed from hucksters and then bragged to the world about it.

Good question, Kate, as usual!

The thing is, there’s are so many side-branches to the Marvelman story that I sometimes had to choose what to keep in, and what to exclude. With Grant Morrison, the fact that he never actually got to write for the strip is what decided me not to include that.

I did deal with it in November 2012, in a piece called Alan Moore and Superfolks Part 3: The Strange Case of Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, and Morrison himself responded, in a piece called The Strange Case of Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, As Told By Grant Morrison. For my money, there are too many inconsistencies in the whole story for me to wish to include it here – for instance, the statement that Dez Skinn offered Morrison the opportunity to take over writing Marvelman, which Skinn must have known was not within his permission to grant. To grant to Grant, as it were. That and the fact that, in the end, this was just someone who wanted to write Marvelman, but was never in the frame to do so. It’s an interesting sidebar to the Marvelman story, without doubt, but it doesn’t really fit in this version of the story.

There is a longer version of all this, though, which does include it, along with various other things that don’t make it into this version which is, remarkably, the short version of events…

I do take your point but I think the Morrison story raises two questions relating to the general story.

First, it raises the question of how the rights situation would have been affected if a party had come aboard on a quasi-work for hire basis for one strip. Presumably Morrison wouldn’t have got a cut of Marvelman as a whole, but would he have retained the rights to this story in particular? That would seem to me to be the case, and was presumably what applied to the non-Leach/Davis artists who worked on the Warrior strip.

Second, according to Morrison’s account, Moore was very possessive of Marvelman in this period. Was this his general disposition or had he taken a particular dislike to Morrison and/or his ideas? Furthermore, since Moore was unhappy with the Warrior situation could he have possibly considered passing the poisoned chalice on at this point – maybe even selling his share to Quality or to a new writer? He would do the latter happily enough only a couple of years later. I’m sure that Skinn would prefer to retain his services rather than take a punt on a new writer for the strip, but was shutting MM down really the only alternative once he and Moore had fallen out?

Chris: the strange thing is, when I started working on this in earnest, I was pretty much writing a purely research-based work. But, along the way, I’ve ended up corresponding with an awful lot of the people involved, and meeting a few of them, as well. I spent a weekend in Northampton, where we met up with Alan Moore a few times, and another weekend at an event called WarriorCon 1, where I spent a lot of time in the company of Dez Skinn. I’ve discussed the ins and outs of the rights to Marvelman with lots of different people, both on and off the record, and you can’t help but be influenced by all that. One thing that I found out I wanted to do, which hadn’t been on my original agenda, was to vindicate Dez, and to tell the truth, as best I was able, about what happened with Marvelman under his watch. He was a man with a burning vision, which didn’t necessarily go as he wished it. But he definitely doesn’t deserve the level of vilification he has suffered all down the years, often from people who don’t know what they’re talking about. I don’t know if I’d want to go into business with him, but my world would have been a very different one if he didn’t exist.

Kate: The thing is, you are speculating about hypothetical situations, which is almost the polar opposite of what this series of pieces is about. Morrison wasn’t taken on as a writer, so the whole situation is moot. Alan Moore had a very definite idea in mind when he started writing Marvelman, and he knew exactly where it was going, and what was going to happen. And it was his first serious long-form comics work. It’s not that he had any dislike for Morrison, but rather that he knew exactly what he wanted to do, and did not want anyone else interfering with it. And, anyway, it was Moore’s writing on the strip that had made it what it was, which was obvious to all, and changing writers at that point wouldn’t have been a wise move.

It’s entirely possible that Dez Skinn might have liked to be able to assign a new writer to Marvelman, but wanting to and being able to are not the same thing, and again we’d simply be speculating, which is not what I wish to do here. The facts are hard enough to pin down as it is, without hypothesizing about situation that didn’t happen, and couldn’t have happened. Obviously, it’s a free world, and there’s almost infinite amounts of space on the Internet, so I’d welcome seeing your own speculations on this, but it’s not something I’ll be pursuing here myself.

Moore didn’t sell his share in Marvelman, but instead gave it to Neil Gaiman when he was done, who then shared it with Mark Buckingham.

The artists on the Marvelman strip in the Warrior Summer Special were paid Warrior’s going page-rate, to the very best of my considerable knowledge, but didn’t own any rights to the characters. They would have owned rights in their own work, though, as Warrior generally only bought first publication rights.

So, is V For Vendetta creator owned? I was under the impression it was a DC property.

V For Vendetta WAS creator-owned until Moore signed on with DC to finish the story. Should have read the fine print on the contract, mate…

This is a terrific series, Padraig. As a serious MM obsessive, it answers a ton of questions. Really looking forward to the next installment. Every Comic Con I hope Marvel will finally announce that they’re reprinting the old stuff and Gaiman is finishing his story arcs.

Thanks. There’s an extra post coming up today, at noon – well, noon somewhere, anyway, but 5pm where I am…

“So, is V For Vendetta creator owned? I was under the impression it was a DC property.”

Technically, I believe that DC owns the rights to publish it in perpetuity, but if it goes out of print then any rights they have would revert to Moore and David Lloyd. That is, same as ‘Watchmen’, but with a different Dave.

Comments are closed.