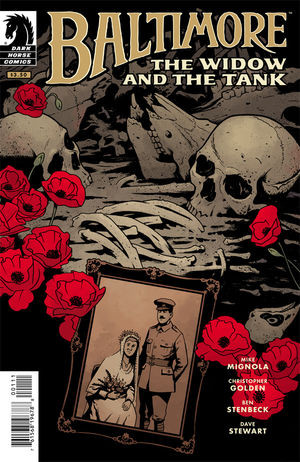

Lord Henry Baltimore, Vampire Hunter, is more strictly speaking the hunter of a specific vampire, as THE WIDOW AND THE TANK one-shot reminds us. For such a goal-oriented guy, he certainly leaves plenty of ash-piles along the way, not to mention the corpses of other creatures he may happen to encounter. Writers Mike Mignola and Christopher Golden team up yet again to present two shorts in a single volume, something of a departure from the earlier longer arcs concerning the exploits of Baltimore searching for his one-eyed vampire nemesis Haigus, though it forms an interesting pattern in storytelling from longer arcs to more recent one-shots like THE PLAY, to this issue containing two even shorter stories. It doesn’t reflect a lack of stories to tell about Lord Baltimore, but instead the variety of stories possible in the life of a man who’s a chronic wanderer with an elusive goal.

Baltimore is a more tragic figure than even Mignola’s internationally known Hellboy despite Hellboy’s part in destined apocalypse. Baltimore’s apocalypse has already occurred in the loss of his previous life and loved ones; in his quest for vengeance he seems more like a dead man walking, though occasionally the ideals behind his quest surface and raise questions for the reader. In “The Widow”, Baltimore carries out a brutally relentless execution of vampires who, having returned as soldiers from the war (WWI), exist now as the vampirical spawn of vampire king Haigus himself. It’s true that they terrorize the village in Lincolnshire they inhabit, and the story is careful to point that out, but if Baltimore’s true target is Haigus, why bother with the small fry? Because that’s what he does. Baltimore appears to have a unilateral modus operandi that not a single vampire who crosses his path will remain in action. But in this case, there may be a secondary motive in the fact that they descend from his hated enemy Haigus.

[Spoilers lurking ahead!]

But there’s more to this story than another stepping stone along the path to revenge for Baltimore. For the reader, the story of the “widow” who conceals her vampire husband, allowing him to feed off of her, is puzzling. This situation introduces a strong human element, and teases out the grey areas in the role of the victim. Mrs. Yeardsley is clearly an abused spouse, shedding tears over her husband’s predatory behavior, but she also reflects the values of the time, 1916, by standing by her man in the face of Baltimore’s accusations. In some ways, she’s the one most in need of being set free, but instead of a hero, she gets Baltimore, who’s happy to play savior on the side as long as it doesn’t interfere with his all-consuming trajectory. In the end, he’ll be both her savior and her executioner since she, too, has become a vampire.

Something that remains intriguing about Baltimore is his exact viewpoint about the relationship between the living and the dead. When the reader views Lieutenant Yeardsley preying on innocent victims, he seems like a monster who should be dispatched, hardly a shred of humanity remaining. But his “widow” is still replete with enough humanity to remain loyal to her husband. However, Baltimore has no compunction in introducing her to a “beautiful day” which reduces her to ashes. Baltimore’s behavior undercuts any reverence for his role while generating respect for a driven man, one who pursues a relentless course in the face of an ambiguous world. For Baltimore, the only good vampire is a dead one, and that keeps his character recognizable and intensely interesting for readers because we don’t fully understand how a person can be so absolute in their actions.

“The Tank” introduces many of the same elements, but also reinforces the wonder aspect of Mignola and Golden’s gothic post-war world where unknown monsters can spring up, all under the shadow of Haigus and his kind. The role of good is just as unclear, however, in “The Tank” as in “The Widow”, which makes it an excellent companion piece. While the widow showed admirable human traits of loyalty, here a vampire camping out in an abandoned tank actually offers Baltimore shelter from other, more powerful (albeit diminutive) monsters. What an unlikely moment in Baltimore history! “The Tank” opens with the pleas of a child for Baltimore to kill the vampire who is preying on his friends, a compelling scene in a country tavern. The child inspires Baltimore to declare, in typical fashion, that he is a hunter of only one vampire: Haigus. What motivates Baltimore to rid the abandoned WWI tank of its undead inhabitant? Is it pity for the child or a chance to learn more about Haigus’ whereabouts? It’s this kind of room for interpretation in Baltimore’s characterization that makes him interesting. He seems to be doing heroic things to make the world safer for innocents, but his words and occasionally even his actions suggest that his motivations are purely personal. It isn’t actually about making the world a better place as it is about making it a world without Haigus.

There’s a fairly iconic moment depicted in “The Tank” when Baltimore, astride the abandoned tank, says to the cowering vampire inside: “Did you think you could next in there forever, eating errant children and passersby, and no one would ever come after you?”. Waiting with his spear, chatting with his quarry, Baltimore really steps up to the medieval monster-hunter tradition that goes back far into the realm of folktales, particularly in European mythology. The vampire might as well be a troublesome troll under a bridge. But Mignola and Golden throw a twist into the tale by pitting Baltimore and the Vampire against the same more deadly foe, inducing the vampire to offer aid. Baltimore is unphased by this, and bluntly refuses help, even finishing off his would-be ally once he’s killed off enough marauding goblins to achieve his own safety.

Could this be some metaphor for war-time enemies failing to find common ground? Poppies are a dominant image in the comic, and it’s possible that finding the vampire in the tank (a wartime weapon), refusing his help, and even killing him reads like an inability to overcome old enmities caused by war itself. There is one final uncertainty in the comic, however, which again places Baltimore’s words in contrast to his actions. In the most gruesome panel, the vampire, being eaten from the inside out by goblins, stares up at the approaching Baltimore, who has just sworn to kill the vampire if the goblins don’t. Baltimore actually ends up putting the vampire out of his misery, the way a soldier might feel the need to end the terminal suffering of a dying man, even a soldier on the opposite side of a conflict. The layers of possible meaning construct several different potential narratives for the reader, a remarkable achievement in such a short format, that helps explain why these two stories were paired together in the first place. They both throw down the gauntlet on moral ambiguity, always present in Baltimore stories, but here placed unapologetically in the foreground.

Because the stories are short and the plots are kept simple, readers also get a chance to see Baltimore operating in more of a close-up. His silences, and his actions become more significant and raise more questions than a sprawling action-driven plot might. It’s a focus that his character deserves, particularly with the success of 14 comic issues over time. He’s no longer an ancillary idea from Mignola and Golden, but a viable scion of the HELLBOY universe in his own right.

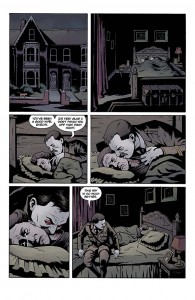

Like any project that Mike Mignola is involved in, artwork is given room to breathe and is held to a high standard. Ben Stenbeck’s artwork is evocative, uncluttered, gives the successful illusion of historical period, and is also versatile in handling the grotesque in a manner that harmonizes with Mignola’s designs. Dave Stewart’s colors make the book work as a Baltimore tale. The series has always been grounded in sepulchral hues, with so many shades of grey and lavender that it must drive a colorist crazy to still manage to evoke difference in shades between panels. But Stewart finds a way to introduce subtle contrasts in “The Widow” that suggest the world of faded photographs as well as the life of a woman living in the dark. The opening artwork in “The Tank” is a little surprising, but a refreshing statement, both in Stenbeck’s depiction of natural settings and in Stewart’s use of brighter colors for countryside and daytime scenes. The red of poppies associated with the fallen of WWI, however, is the most striking feature. A feature associated with artwork in Mignola’s HELLBOY but also present in THE WIDOW AND THE TANK is the well-chosen panel “moments” in battle scenes. There’s an economy in blow-by-blow action that makes this Baltimore comic highly readable without downplaying the major role of physical combat in the series.

The various aspects of comics storytelling that fit together in this one-shot suggest a well-oiled machine of a team who understand what goes into making a sophisticated comic. BALTIMORE comics have done well so far, and this one-shot doesn’t show any signs that the character or well of potential plots have lost their edge. In fact, Mignola and Golden take the opportunity to examine Baltimore’s action and motivations more closely, giving added depth to the character and the world he moves in. As THE WIDOW AND THE TANK shows, Lord Baltimore may be single-minded, but that doesn’t mean that his stories can’t contain hidden depths.

Title: BALTIMORE: THE WIDOW AND THE TANK/Publisher: Darkhorse/Creative Team: Mike Mignola, Christopher Golden, writers/Ben Stenbeck, artist/Dave Stewart, colors/Clem Robbins, letters.

Hannah Means-Shannon writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress.

Mignola and everyone who works on the Hellboy universe at DH are really a gift to comic fans. It seems that everything fans complain about is actually handled well at DH. You get a lovely amount of characters, progressing storylines and there actually is a huge pay off if you read everything because it actually does all tie together. Or you can take great little one-shot stories like this.

I agree- it’s not just that the universe of all the comics is technically consistent but that it feels the same- even with diverse artwork and various writers. It’s real universe building and quite a feat.

Comments are closed.