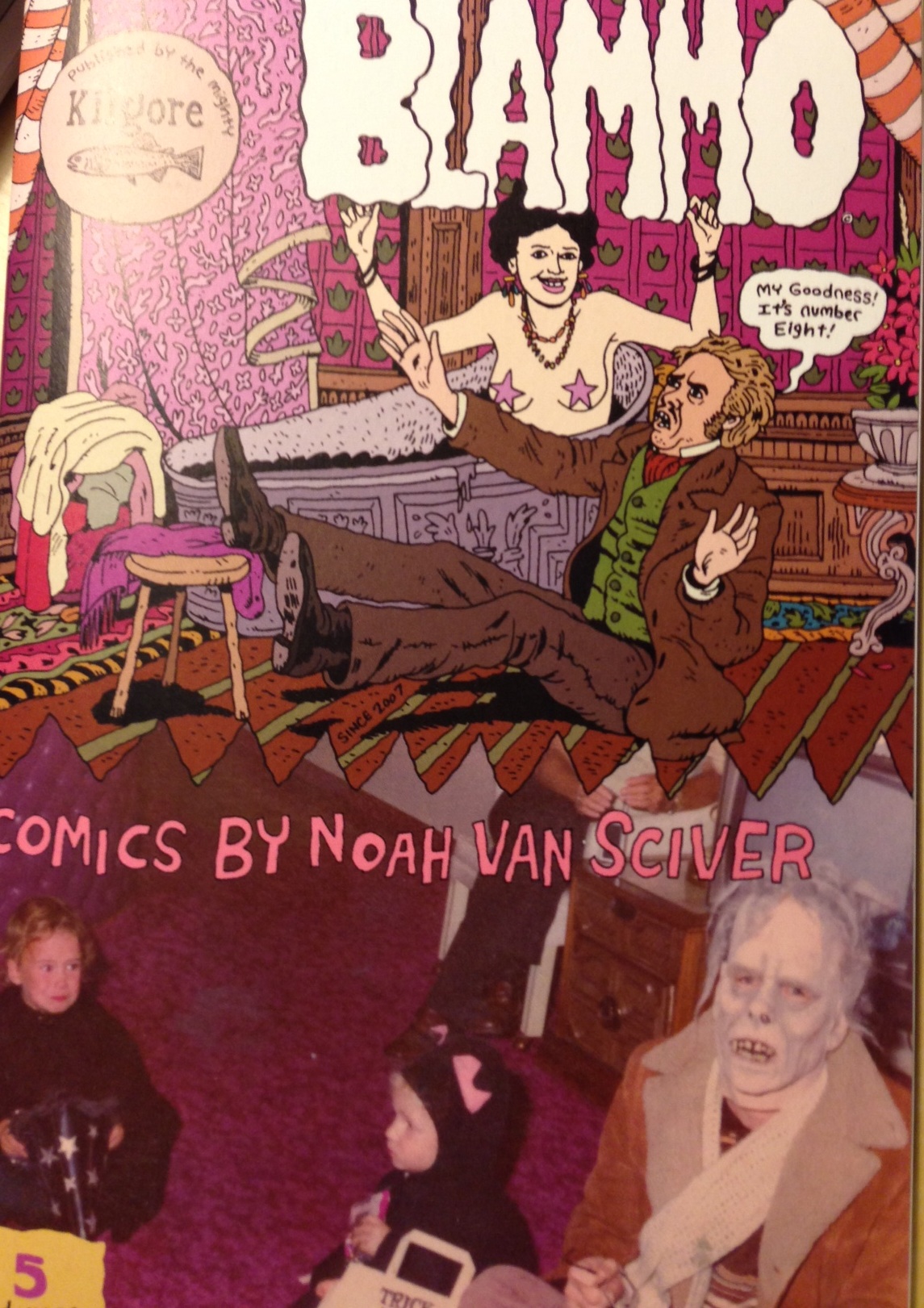

Noah Van Sciver possesses one of the most original voices in indie comics. There’s little doubt about that. But he’s been on a strange road of personal exploration that has led to some big successes and currently he’s taking stock of what he wants to draw and how, while also continuing to work on new long form comics on The Expositor website with Joseph Remnant. In 2012, Van Sciver produced two longer form works, 1999 from Retrofit Comics, and the critically and reader-acclaimed Lincoln bio THE HYPO in hardback from Fantagraphics. During this period, he considered working “full time” as a comics artist, but the experiment left him with some questions, particularly since it led to the postponement of his long-running personal anthology BLAMMO, nominated for an Ignatz Award in its sixth issue. He wasn’t able to produce BLAMMO yearly as per tradition, and with BLAMMO 8 now in print, he says in the book, “At some point I came to the conclusion that I could never be a full-time cartoonist. I gave it a good shot, but I don’t want to burn out. And I want to draw only what I want to draw”. It’s brutal honesty from Van Sciver, but makes you wonder if the production volume necessary to be a “full-time cartoonist” is the problem when his work, and ideas, are excellent and necessary to keep pushing the envelope on indie comics today.

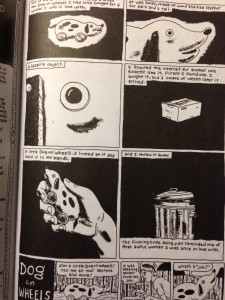

BLAMMO 8 is what Van Sciver “wants to draw”, so taking a cue from it shows a wide range of his ideas and talent, and illustrates his need to bring diversity to his work, something that even producing long-form works is not necessarily doing for him. Anthologies are clearly what he feels meet his personal needs, and it’s a wild, carnivalesque ride in BLAMMO 8 through Van Sciver’s imagination. All of the stories strike their own balance between stark panels, often emphasizing a person or an object to suggest psychological impact and an organic density of detail that’s intentionally claustrophobic and renders the worlds of the stories active, almost predatory. One of my favorite features of BLAMMO 8 is the introductory, and recurring, motif of the wooden dog confessor, “Dog on Wheels”. The dog is explained as the exact replica of one the narrator gave to a woman he loved once, so replacing it to consider the strange toy more fully, he finds that it seems to demand him to tell “his secrets” to it. It’s an ersatz object, disturbing to the narrator, and the reader, but it points out the intense loneliness of the individual as more characters continue to return to it as a confessor throughout the anthology.

In the long-form story “Expectations”, containing a wide array of characters and intense “slice of life” experiences, objects also play a totemic role, this time a figure of a devil. We get closer to the significance of objects like this in Van Sciver’s comics in a panel that reads “And sometimes no matter how close you are with somebody you’ll have to let go of them. And you should. Don’t try to hold on”. The objects are often proxies for relationships, highly-charged and symbolic, that physicalize the idea of holding on or letting go for the “collectors” in the story “Expectations”. This is something that the visual medium of comics can do so well, presenting a physical sense of objects and the resonant roles they certainly play in our lives.

“Charles the Chicken Gets Tough” and “The Wolf and the Fox” are also stories about relationships, but the terms are transformed into non-human counterparts with the same themes, maximizing the impact through ascending to fable. There’s nothing limiting about telling an honest to goodness realistic story about human beings, but transferring the ideas to cartoony or animal figures does make a lasting impression on readers. The transfer can get around having to include heavy contextual detail to make relationships feel “realistic” while paring down the conflicts to their key elements. Charles, trying to resurrect his lost friend in desperation, finds that neither heaven or hell are as faith-destroying as loneliness, while Van Sciver’s Wolf (based on the Brothers Grimm), beautifully rendered in medieval fable style with ornamental framing by the way, finds that a dominating relationship is no relationship at all.

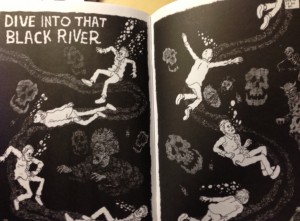

The crowded, intricate details of “Punks vs. Lizards” show off very pointedly what Van Sciver wants to draw, stories of humans under pressure and the freedom to get as weird as he wants in terms of high school settings, unlikely violence, and even idiosyncratic dialogue. At one point, a lizard-fighter declares regarding a pair of reptilian monsters, “What a cute couple. Let’s destroy them!”. The sheer energy of the artwork on this story says a lot about Van Sciver’s ability to “get real” as an artist with the stuff of his imagination. The most fantastic elements of BLAMMO are often the most detailed and self-possessed in their rendering. This is the kind of autonomy that shorter works, and anthologies offer Van Sciver. The double-page psychological spread near the conclusion of BLAMMO 8 seems to argue the same point, “Dive into that Black River”. It would make an excellent fine-art poster, heavy with enough archetypal meaning to speak to any reader. As a central figure, alarmed and concerned, drifts past phantoms, fears, and possibly loss, he comes to equally disturbing conclusions. It’s a narrative in only two panels with only one text box, and so could never become, in its simple, focused impact, a long work, but the anthology format gives it a place to reach readers and gives Van Sciver a chance to draw what he most wants to draw.

BLAMMO 8 is a tour through the most pressing storytelling needs of an indie creator on the move, trying to decide the modes that suit his work best, but it’s also a highly compressed intensive labor that, even if composed over time, represents a substantial new body of work. His commentary on the role of BLAMMO in his life provided in the book suggest that it contains some of the things that are most strongly on his mind right now and the things that he’s simply itching to draw and that’s exciting for readers because its so direct, personal, and unfettered.

Hannah Means-Shannon writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress. Find her bio here.

Comments are closed.