With comics having reached a hitherto unseen level of respectability, that’s the cue for the comics literati to go back to the begining and argue about how the whole thing works…or doesn’t.

In a simultaneously rambling and incisive interview, Tom Spurgeon asks Fantagraphics publisher Gary Groth about all the matters of the day—publishing deals, young cartoonists and their expectations and storytelling ability, Spain Rodriguez. It’s full of pull quotes, but I’ll pull this one on the nature of comics:

SPURGEON: You always struck me as a guy that maybe didn’t have a special connection to comics as comics.

GROTH: That’s not true. I do love the form. I love the drawing. One thing I would love to do — one thing I love about comics is the line. It’s so important. I could see analyzing nothing but the line. You could blow up 30 cartoonists — Segar, Jaime, Crane — just blow up their line. I think that’s so big of a component for the expressive nature of comics. I think everyone acknowledges this, perhaps subliminally. But probably not as much as they ought to. Not as much as they do content. But in a way, it is content.

And that brings me back around to something I’ve been avoiding talking about, all the various responses to Eddie Campbell’s essay The Literaries, which I tackled a bit here but then the argument went round the bend and in only a few paragraphs, AN AMERICAN IN PARIS (the movie) and Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” had both been declared substandard and I threw up my hands, grabbed my glove, and went home.

While my back was turned, Robert Stanley Martin—who is known for his strong message board postings—came back to put down the “let comics be comics” crew::

That’s right, folks. If you’re reading a comic for the overarching story, and judge it by how effectively it tells that story, or even to what extent that story is worth telling at all, then in the view of Eddie Campbell (and Dan Nadel and Kim Thompson and Jeet Heer and Tom Spurgeon and Heidi MacDonald and numerous others), you’re reading and judging it wrong.

Part of me just wants to point to Eddie’s article and its reception among the comics-cultist crowd as Exhibit A as to why none of these people should be taken the least bit seriously as critics ever again. They’re of course entitled to their enjoyments, but they are so preoccupied with their abstruse little fixations that they seem completely divorced from the impulse that guides people to becoming audiences for cartoonists and other storytellers in the first place. The reason I can’t entirely dismiss the essay is because I’ve seen similar arguments in a field outside of comics, where they’ve been around for six decades and don’t appear to be going away. They can be found in film criticism, where they are a key part of the auteur theory.

For the record, if I enter a room and Robert Stanley Martin is standing on the right side, and Eddie Campbell, Dan Nadel, Kim Thompson, Jeet Heer, and Tom Spurgeon are standing on the left behind a wall of crocodiles, I will drag myself on bloody stumps, if need be, to get to the left side of the room.

The whole discussion led to a roundtable of such grave import that it caused Noah Berlatsky to quote both a Russian poet and Steven Grant, and Jones, one of the Jones Boys, to wonder whether Borat was funnier than Aristophanes.

I don’t normally give much time to the Hooded Utilitarian drumming circle, but the fundamental question—are comics to be judged only on narrative or on a mix of narrative and art or on some other quality?—is a bit silly, but definitely something to examine just in case there’s a test.

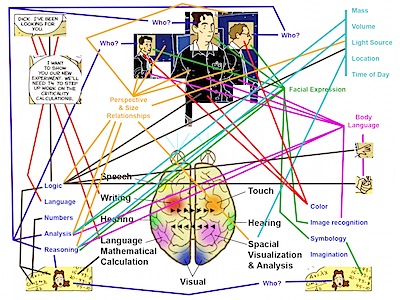

Campbell put it all on the line again with a subsequent post entitled Campbell’s Rules of Comprehension in which he analyzed a random comics page from near a hand —in this case from Bryan Talbot’s GRANDVILLE, and noted how it stacked up against his own storytelling rules for civilian comprehension:

Occasionally I see a well-regarded comic wander across the view of a regular person. It happened on my travels recently when I was a houseguest of a friend, a 70-year-old lady who makes her living as an artist. While I was there she was working on some etchings to go into a limited edition anthology of poetry on the subject of war. I mention this simply to show that this person understands pictures. The mail arrived and among it there was a volume of Bryan Talbot’s Grandville, which her husband had bought. She opened it and checked it, in order to let him know by phone that it had arrived. While idly looking at the pages she confessed to me, after putting down the phone, that she didn’t know how to read these graphic novel things. I took a quick look and said, “My first thought is that I can completely understand what you’re saying, because I can see that the author in this case has broken at least three of the basic rules of comprehension.”

Campbell’s rules were given an interesting reading by Neil Cohn, who has been gathering studies on how we read comics from behavioral and neurological viewpoints. NOW we’re getting somewhere.

Overall, I found that American comics used far more panels showing multiple interacting characters than Japanese manga, which used overwhelmingly more panels of single characters or close ups. This would support that American books use more sequences following “Rule #1” [All the information necessary to understand the drama of a sequence must be contained in every panel of the sequence.] than Japanese books. This difference has an impact on comprehension. Being provided with only parts of a scene (single characters) forces you to infer the larger scene. This requires more machinery in the narrative grammar (what I call “Environmental-Conjunction”), i.e., the rules in people’s heads that allows them to comprehend sequential images. Yet, this does not necessarily lead to poor comprehension. Rather, it simply reflects a different grammar along with the need for a different type of fluency. Neither is better or worse. Just different.

If you haven’t thrown down your pencil in despair by now, Cohn’s post actually has a lot of interesting info on studies that show how people read comics, absorb information and so on.

As someone whose comics making career rarely got beyond checking to make sure that Huey’s shirt or cap was colored red, and not green or blue, I did not find this to have very practical applications.**

So who to give the final word to? Why Colleen Doran of course!

Art may be easy, but stop lying to people Gurus of Art Twee. GOOD ART IS RARE AND IT IS HARD.

** How did I know this? Because of the beautifully elegant pictograph that an editor named Bob Foster had over his desk that read

Huey

Dewey

Louie

“I was like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

~Isaac Newton

Over all, I think it’s too soon to look for all of those hard and fast rules, that unifying theory. In truth, I don’t think there is one. I think out of all the storytelling mediums, comics are the one with the most undiscovered potential. They utilize and engage more of our senses, through interactive psychic connections. They do not suffer from the limitations of language, like books do. (Don’t jump on me for that. I love books.) They can deliver multiple units of thought, simultaneously, without the restrictions of time that movies or plays have. Movies can’t really engage you at all. They are simply an assault on your senses, leaving you at the mercy of the people whom make them, within the limits of showtime, as they manipulate you. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it gives you no room to engage the movie back. It is what it is, from the moment is starts, until the moment it’s done, and it plays on, with or without you. Cut the power, and it’s over. Comics (and books) lay inert until a reader picks them up. They are our tree falling in the woods, and we need to be there, for it to make a sound. The reader’s mind has to meet it half way, activating those sounds, smells, and voices, making still pictures move. We, as readers, can exist outside of time and space. Like I said before, there is so much potential in that; so much undiscovered country. How can we possibly define that, yet? Who has the right to wag their finger, when non of us could possibly be competent enough to know the terrain of those said countries? To do so, is to let the air out of our tires, before we can get out of the driveway. I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Reading all this reminds me of the generally held belief about humor: If you want to kill a joke, analyze it.

Maybe Campbell’s 70-year old friend, “who understands pictures”, couldn’t read the book because she didn’t “understand” pictures + words + narrative conventions.

Maybe he should have given the book to a 7-year old, and see what she could make of it.

I think Eddie made some very good points. Must 7 year old’s understanding of anything is going to be limited, no matter how well a narrative is laid out. They just don’t let it bother them. Sure, you can kill a joke by explaining it, but you have to understand it, to know just the right way to deliver the punchline. As a creator, writer, or artist, you have a responsibility to know why you do the things that you do, or else how can you expect your reader to? Never make it hard for your readers. Eddie was very clear in saying that these were his rules, but not thee rules.

Forgive my typos. I’m working and commenting, at the same time.

That’s a whole other ballgame. Torrent has nothing to do with vocabulary or medium.

Bookmarking all this for my graphic narratives course in the fall . . .

Rob, may I recommend Eddie Campbell’s links of Comic Book Craft…

http://eddiecampbell.blogspot.com/2007/05/comics-craft.html

“For the record, if I enter a room and Robert Stanley Martin is standing on the right side, and Eddie Campbell, Dan Nadel, Kim Thompson, Jeet Heer and Tom Spurgeon are standing on the left behind a wall of crocodiles, I will drag myself on bloody stumps, if need be, to get to the left side of the room.”

That’s a great line!

Love the shout-out to Bob Foster . . .

RDaggle is on to something, to quote the text:

“…I mention this simply to show that this person understands pictures…. While idly looking at the pages she confessed to me, after putting down the phone, that she didn’t know how to read these graphic novel things. I took a quick look and said, “My first thought is that I can completely understand what you’re saying, because I can see that the author in this case has broken at least three of the basic rules of comprehension.”

This seems to be exploting the fallacy that someone who “understands pictures” is an expert on all forms of graphics. This is comparable with assuming that a Shakesperian actor could immediately grasp the nuances of Kabuki or Noh drama. While there is considerable overlap in required skills, the means of expression and context is radically different.

Now consider, if that Shakesperian actor were to make a new version of a Kabuki play, which might seem avant-garde to the general public, but be received by the Kabuki as tone deaf, boorish, and passe. In far too many cases this is what happens when “hip” artists invade comics.

Personally, I do not create to be understood. I find Picasso’s “Guernica” difficult to interpret. It can be read in a number of ways, yet it is definitely great art by a genius. Harold Pinter’s work is obscure and confusing. Some Jimi Hendrix solos sound like feedback noise. All of these people are great artists. I’m looking at a Georgia O’Keefe picture on my wall. I have no idea what it is. I think it is a picture of ice, but it could be clouds or lily pads. Perhaps it is all of these things. She is a great artist.

Bookmarked, Christopher Moonlight! Gracias!

@monopole

I understand what you’re saying, but I don’t think your example applies to Eddie’s rules. You’re speaking of exclusive vocabularies (which can be trumped by universal themes, by the way) where Eddie is speaking of natural tendencies of the brain, which he has designed approaches that he hopes will cater to them. A good example is in his theory about how the eye naturally follows word balloons.

Bloody stumps aside, Heidi, do you see yourself as a critic who impugns ordinary, “let’s-read-a-story” narrative as against some more abstract measure of narrative excellence? (My translation of what I *think* Martin is saying.)

I would think that you’d at least be in the middle of the room if just Domingos and Tong the Tedious were on the right side.

Speaking as one who was an English major many many years ago, art/comics/film criticism isn’t necessarily for lay audiences, it’s to give people who are interested potential deeper insight into the art and, perhaps, provoke further ideas and insights. But it doesn’t detract anything from the original piece of art or one’s enjoyment of it (regardless of what level they’re reading it), so I don’t see why people get uptight about it. As an artist, I appreciate Groth’s appreciation of the joy derived simply from the unique line of a cartoonist. Again, that doesn’t take away from the rest of the art, but it’s an insight worth considering.

We should be glad that comics are layered enough to be looked at so many levels. Yes, it’s just “entertainment,” but most artists try to transcend that in some way and such critical analysis honors that.

Comics are a meeting of words and pictures, so both should be viewed together. It’s the synthesis. Even if a story has no words, there is still a story, a thing to connect the pictures. And a story without pictures is not a comic. I think this boils down to folks still subconsciously seeing their sequential artisan fanaticism as juvenile. It’s not that complicated. There are countless aspects that can be weighed, but focusing on any singular aspect betrays what the medium is all about.

@Kyle Baker: actually, Picasso’s Guernica is rather easy to comprehend and there is but one way to interpret it: as a cry against war.

“An American in Paris” always got a bad rap from certain film buffs, mainly because it beat “A Streetcar Named Desire” in the 1951 Best Picture Oscar contest. And “The African Queen” wasn’t even nominated!

Also because it supposedly isn’t as “cinematic” as the next year’s “Singin’ in the Rain.”

But “American in Paris” is undeniably a great movie. And “Strange Fruit” is a great (and important) song. It’s not necessarily the first Billie Holiday song I’d like to hear — and she didn’t exactly “enjoy” singing it — but its greatness can’t be denied.

I have to admit much of this goes totally over my head, but as far as reading and understanding comics goes: my parents were immigrants to the UK, my mum had no English whatsoever- when I picked up Tintin at the library when I was 7 or so, I had zero problems in following it.

I understand the passion behind dissecting and analysing this stuff, but I think sometimes it can get really over wrought :)

just like any other field, understanding art is about education. Taught or self-taught. You won’t understand Math just by sitting in front of an equation written on a blackboard. Same for Picasso. Or graphic novels. Quality of narration also counts of course. Tintin or some manga work for youngsters because it’s pure, broken down to basics approach to narration.

You could teach yourself to read with comics in the 50s because captions and bubbles exposition overlapped graphics.

You can’t do that anymore because most of today’s writers and artists are glorified fanboys who don’t know squat about the basics of narration.

Most of today’s successes in popular art appeal to emotions and not to intelligence, like FIFTY SHADES, Michael Bay’s movies, Warren Ellis’ or Mark Millar’s comics spring to mind.

Which is why you will never see a good novel by a modern comics writer.

I’m looking at you Neil Gaiman.

Comments are closed.