Here in the city, there was a man I call “Uncle Frank”.

I met him just a few months after Danica and I opened our store. He walked in with a bottle of wine he had purchased to drink with his wife over dinner – a trip he admitted to making quite often.

After a few pleasantries and a bit of chatting, Uncle Frank asked if we’d be interested in purchasing some comics he had.

“They’re leftover from when I used to run a comic shop myself,” he said, “They’ve been in my basement for decades, and I was wondering if you had the time to look at them?”

We exchanged information, and later in the week, I’m in the basement of Uncle Frank’s sprawling house that overlooks the Groat Ravine. It’s filled with all kinds of knickknacks collected over a long life. The comics are buried among other treasures that we dig through, including boxes of different songs he’s co-written (which a search through the internet proved to be true). Uncle Frank casually talks about his music career and walks through a few stories that I can’t confirm in the slightest. At one point, we come across a gold record. He treats this like everything else he comes across, with a clear fondness that he floats past, never stopping to elaborate because he’s already onto the next thing he’s remembering.

After a while, we finally feel like we’ve uncovered every box that has comics in them. While I slowly go through the box, Uncle Frank tells me about how he used to run his comic shop in the 70s.

Originally, he dealt in selling metaphysical books, but figured there would be a market in single issues. He said he approached a local magazine distributor and worked out a deal with them. He’d go to their building every week when the comics would come in, and he’d nab the comics and quantities he was interested in carrying. Uncle Frank claimed that this system worked for quite some time. Folks began to realize he could get specific comics in with regularity, and the magazine company didn’t seem to mind the increase in volume they were moving. Things were good… until they weren’t.

According the Uncle Frank, he showed up to pick up comics one week, and the magazine distributor told him the deal they had was off due to it “messing with their system”. He asked if he could nab this week’s books as a capper to their previous agreement, and they obliged. While he was happy he was able to get one last “shipment”, he was upset that he’d have to disappoint his customers soon.

“So I picked up the phone and I phoned DC,” Uncle Frank told me, “And when I got ahold of them, and I told them my situation, they were mad, they said ‘fuck them’. They have me talking to this guy, he says he’s Carmine Infantino, and-”

“I’m sorry,” I interrupted, my hands stopping their gentle stroll through dusty books, “Carmine Infantino?”

Uncle Frank regarded the name with casual fondness as the gold record. He did this a lot, dropping something wild but only because his brain had produced the tidbit. The man didn’t seem to have an ego about any of his life, just a calm sense of contentment.

“Yeah, and he makes me a deal, to let me distribute their comics, over the phone,” Uncle Frank said plainly, “And so I figured if that worked, I better phone Marvel and get those too.”

He relayed this information, sitting in a big, comfortable chair as I dug through long boxes. I would occasionally come across many key books in this collection and point them out to him.

“Oh wow, Giant Size X-Men #1,” I would say, “This one is worth a bit of money.”

Each time, Uncle Frank would wrinkle his brow, repeat the name of the comic, and then relay memories of the business surround that book, such as, “People seems to like that one. I remember trying to get more of that one when I could because they liked it.”

Then he would take a small pause and, with no hint of playfulness or irony, guess at the price.

“Figure that’s worth… $250 maybe?”

After the third or fourth book like this, I told Uncle Frank that we’d be selling his collection on consignment instead of buying it outright. At the prices he was guessing, we could have made a lot of extra money, with him being none-the-wiser. Instead, I listen to Uncle Frank’s stories, about how he got into underground comics and started distributing single issues to all kinds of stores in Edmonton, head shops, used book stores, music shops, and so forth, in addition to his own store. At that point, I had been working in a comic shop in the city for about 9 years and had never seen any of the old undergrounds, but here were boxes of them.

When I’m done looking, I ask Frank if he’s comfortable with me taking the long boxes to the shop to process them and sell. I ask him if he wants anything written down. He does not.

“You seem okay,” he said, “And that’s good enough for me.”

It takes two trips to load the comics into the car, carrying boxes up several flights of stairs and through the front of the house. Frank would tell me about his wife and his family when I needed to stop for a few moments.

When I finished the last load and get ready to leave, he stopped me.

“Hold on,” he said, “That was a lot of work.”

He opened one of the kitchen cupboards and produced an incredibly large bag of roasted nuts that he and his wife had seasoned and roasted themselves. He filled a small sandwich bag and gave me a bunch.

“You need to eat,” he insisted.

I take the bag and leave, filled to the brim with stories that… I can’t even begin to confirm, but just feel true in my guts. Stories about a history that has always fascinated me, but I had only been able to scratch the surface of in my time behind the counter.

The comic book industry was always a passion of mine, but there was something about Uncle Frank’s strange, breezy way of describing how he cobbled together comic distribution in Edmonton that had me craving more. I spent the next few years trying to dive into the history of the industry and the direct market specifically.

Through the years, I’ve amassed quite the collection both physically and digitally, ranging from histories of specific companies to the nitty gritty of comic retail and everywhere in between. I devoured books like Comic Shop by Dan Gearino, where I learned about Robert Bell and Phil Seuling. I read about literal children pooling their money together or borrowing from their parents to run small comic shops and the weird, nebulous handshake deals that led to the first direct market distributors emerging. There was also a tale where a young Bill Schanes was approached by a distributor rep who started a meeting by opening up a briefcase that had a bottle of whiskey, a couple of shot glasses, and a gun. Schanes, who was in high school at the time of this meeting, refused the whiskey. Schanes would go on to be the Vice President for Purchasing for Diamond. He started his shop when he was 13 with his brother, who was 17.

The stories of the direct market are wide and varied. You have the wild formation, the folks like Uncle Frank and Seuling and others cobbling together a system, wrangling many actual children and starting direct distribution. You have the refinement of that system, which evolved to do away with much of the “direct” aspect as the business grew. You had many distributors melt away until there was one, and you had the retailers who tried (and sometimes succeeded) in help steer large companies and distributors in helpful directions.

All through this, good work was done. Good work, by good people, all trying to do their very best.

In the coming weeks and months, I will be celebrating many aspects of the direct market. Wild and unwieldy, it was something that the industry needed when comics were struggling to appear on the racks of newsstands like they had in their heyday. The direct market was a haven and a life raft. It wasn’t perfect, but nothing really is.

That said, today I’m not here to celebrate the direct market. I’m here to bury it.

The time has come to say goodbye.

By Brandon Schatz, with edits and contributions by Danica LeBlanc

In the final edition of The Retailer’s View, I described the times we’re living in as “post-normal”. The chaos caused by climate change is taking root and getting worse. The pandemic is still not over, and at this point, despite our fervent wishes, there doesn’t seem to be a timeline for things to settle.

In reply, the structures we’ve built as a society have revealed their many faults. For some, these faults have been apparent their whole life. For others, these faults have come as a surprise. The systems we’ve put in place were not meant for the strain or scrutiny they are currently under. Late-stage capitalism is collapsing. Health care systems are collapsing. The direct market… is collapsing.

For that last point, I want to be clear: when I talk about the “direct market”, I don’t mean “the comic industry”. People often conflate the two, and I take great pains to separate them. They are different entities.

The direct market, as an idea, was built in the ’70s as a means to satisfy collectors, and to provide a new means of solid distribution. The newsstand was abandoning the medium, and the comics that were distributed were done so without quantity control in the picking of titles. A mutually beneficial solution was made whereby publishers could sell product on a non-returnable basis to a rabid fanbase, while said fanbase developed shops where content and quantity could be curated.

Today, things have changed significantly. Gone are the days of publishers scrounging for a way to find an audience. Hollywood is hungry for content, and our industry is full of concepts being developed on the cheap. In the grand scheme of things, DC and Marvel and others don’t need to go around making handshake deals and selling comics directly to teens. There are millions upon millions of people loving the stories that come from this medium.

They just aren’t reading the single-issue comics.

The reasons for this are legion. Where once there was a time where you had to make sure you were in the right place at the right time to catch your favourite show or buy your favourite comic, almost everything we’ve ever loved is now available for us to experience within the span of five clicks or taps. Content across all mediums has become an unending torrent.

The way people want to consume media has been completely changed. If we have to wait for the next installment of something, we want it as quick as possible. To fill the time, we seek out something we loved from the past, even as we amass a pile of unread books, unwatched shows, and unheard music or podcasts. If we love a thing, we want that thing to be a fire. We need it to be brighter than all the others, to eclipse the urge to just go with a tried and true favourite.

We are a society that no longer wants print single issues.

Now, before you go breaking a monocle, please know that when I say that, I don’t mean that as an absolute statement. I don’t mean every single person on this earth is done with the format. Far from it. I mean the larger collective, the masses, do not want print single issues. In the coming weeks we’re going to be talking about this in depth, but for now, I’m going to give you some quick numbers that I want to use as a conversation point.

A few months ago, I dug through all the sales data that I could find from Comichron’s yearly wrap ups, and I went and grabbed every single print single issue SKU (individual items offered, including variant covers) Diamond offered from 2011-2020. (For the 2020 data, Diamond still had order codes for all of DC’s books, and Comichron accounted for sales outside of Diamond.)

I smashed those numbers against each other for a while, getting numbers for the amount of $ generated per SKU, running that against the average cost for all the books total, in order to discover the estimated average of copies sold per individual SKU offered.

Before I share those numbers I want to note this: due to a TON of different reasons, this shows nothing more than an estimated trend. There was no balancing done for how a 1:500 would effect the numbers both as it’s own SKU or how it would increase the orders of another, for instance. Regardless, I think this paints a picture of the increased effort retailers are having to deal with. If each SKU represents a certain amount of time and effort, you’d want each item to be generating as much interest as they can, right?

Estimated Copies sold per SKU

2011: 9,152

2012: 10,490

2013: 8,396

2014: 5,129

2015: 4,797

2016: 5,136

2017: 4,248

2018: 3,698

2019: 3,512

2020: 3,620

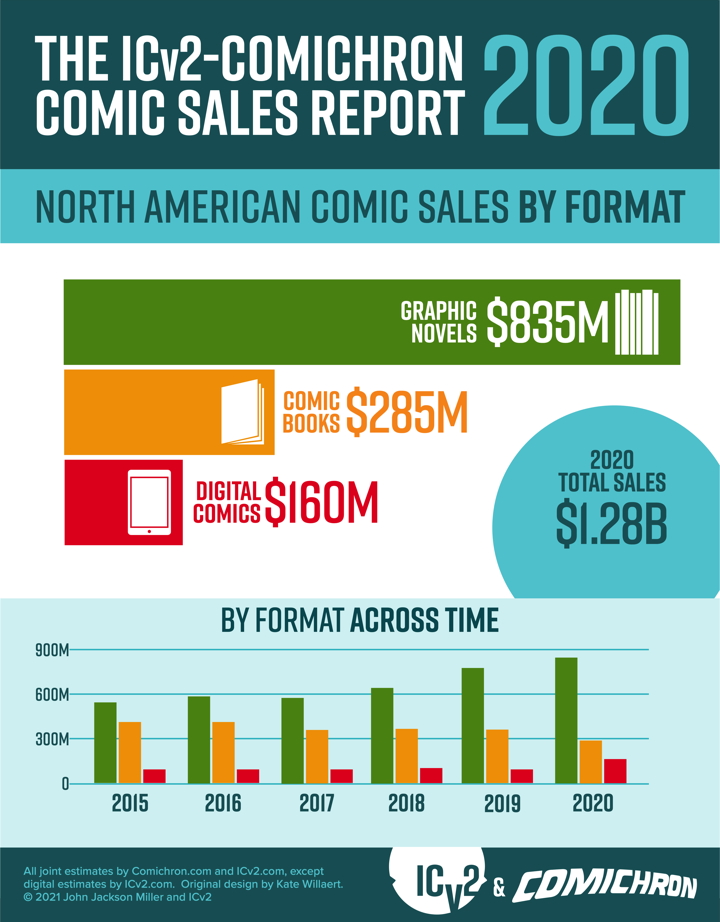

What you see there, is an estimated measure of effort increasing for the results that the industry is seeing. To that end, look at what single issue sales have done over the past six years.

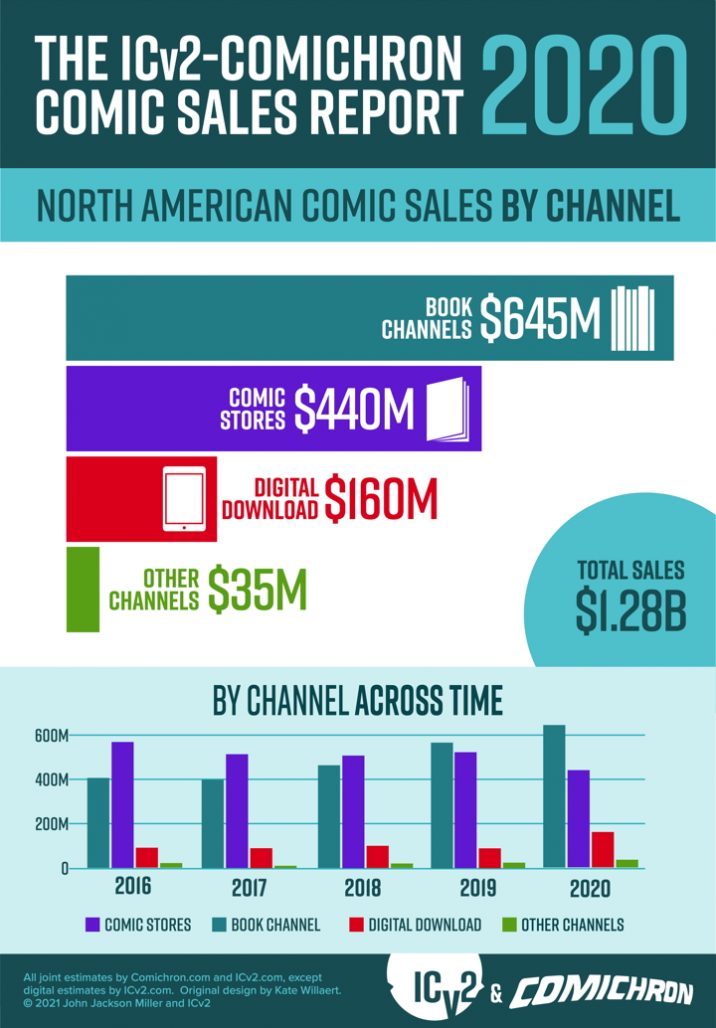

Now compare that to the industry as a whole.

Now look at the past couple years of sales specifically through the traditional direct market channels.

The industry is saying something. The people are saying something.

And yes, I know many comic book stores actually account for a good chunk of the orders in the “book channel” column as many stores are ordering from book channel distributors to get that stock in. I would suggest that this proves that many comic stores themselves have identified the lack of strength in what the direct market has to offer today, in choosing to work so readily outside of it.

Things aren’t changing. Things have changed, and they changed a few years ago. Everything that’s happening now? It isn’t the cause, it is the effect.

When we have heat domes and hurricanes and flash floods and wildfires… we see these things as causing a change in our lives, whereas they are truly an effect of how we’ve been running this world. Change will come more rapidly as a result, because things have to change, but the fact of the matter is, the cause is in the past, and it is immutable.

The pandemic is similar. People were warning us for years that the next big problem would be a pandemic. Heck, part of the reason vaccines were produced so quickly were because certain folks were and are maintaining the building blocks needed for quicker development to prevent something worse from happening. But again, the pandemic isn’t the direct cause of all the changes we’re experiencing. What we’re experiencing is the effect of the US terminating integral programs to monitor disease in other nations, and the supply chain shortages are the effect of a society built on exploiting a mass of workers to the point where we’re willing to make them sick during a pandemic to get our comforts, and the rippling effects from there.

We passed the point of no return a while back, and what we’re experiencing now is an acceleration that will not end until there is a reckoning. And even then, change will come slow due to the momentum that’s already been built up.

In a very small way, the same thing is happening within the comic book industry. The direct market is a structure that has not been relevant for a while. Shops have been buying outside of it for quite some time in order to keep things running.

The publishers have seen this coming, and have jumped in many different ways, resulting in a fracturing of distribution. You’re also seeing more attempts at other dominant markets such as what’s been accomplished over at WEBTOON (a subject for another column) and the YA graphic novel market.

As time marches on, the direct market, such as it is, will not be along for the ride. Something new will be in its place. Or rather, something new already is. Privately, I’ve been calling this new thing “The Indirect Market”, as a nod to the past and an identifier of the complexities this new market has. This system has multiple distributors and more flexibility. It focuses more on story than collecting. Much like the direct market, it lives and breathes through the efforts of those working within it to make it bigger and better.

It isn’t perfect. It needs work, and I’m hoping to do some of that work here.

For the past few months, I’ve been digging through old issues of Comics (and Games) Retailer, gleaning messages from the past. The run starts a little before Marvel buys Heroes World and then rockets through to the dominance of Diamond before finally sputtering to a close as the internet becomes a more and more dominant source for more timely information.

What I love about those magazines are the touchpoints where retailers and others are all looking at a shifting business and trying to figure out a path forward. I was lamenting the fact that not many retailers seem to be doing this now. Most seem to be content with picking fights or dropping complaints in a quick hit on social media and calling it a day. I can understand this, as that’s all many of us have time for these days. (And beyond that, many of them have already done their time chronicling. Brian Hibbs, somewhat solely, continues to do so today.) Then a few people in my life (including Danica and Heidi) reminded me that I do have a platform for this kind of thing, so I’m going to use it.

With The Indirect Market, I hope to chronicle the living history of this accelerating shift. My intent is to tackle this in two ways. The first is the biggest: the columns you’re reading now. Including this one, I have blocked out the time to write nine columns before the end of the year to kick this off with as much groundwork as I can possibly lay down. In the coming weeks, I’ll be talking about Substack, WEBTOON, Panel Syndicate, Marvel’s shift to Penguin Random House, online store and subscription options, alternative distribution methods, supply chain issues, and more. I’m going to encourage other retailers to provide rebuttal as they have the time and inclination, though I’d suggest they do so by contacting me directly if they have the information, or by approaching Heidi to run an article. The more perspectives on these changes, the better!

Second: as a test to see if I could keep up with a writing schedule, I started a Substack revolving around this idea as a place to test out bits and pieces and vent about more personal aspects of retailing. A few weeks later, the Substack deals with comic creators started being announced, and I knew it was time to kick things off properly.

The plan will be for ideas that have percolated and gelled to appear over here as full columns. The development and much of the “day-to-day” will be chronicled over on that Substack. I haven’t decided on a schedule for that newsletter yet beyond “there seems to be enough content to send”, but the column over here will happen twice monthly (with only one in December) as of 2022.

This is ambitious, but I think someone needs to be watching all of this and writing things down. You might not want that person to be me, and on that point, we agree. I hate my writing and I’d be far more content putting the words down and deleting them all with shame over and over and over again (or as I like to call it “my writing style”). But for now, I’m who we have.

NEXT TIME…

I’ll be back a week from today to talk about comic creators and companies finding success in monetizing their projects online, and what a retailer should be doing about it.

Until then!

PROGRAMMING NOTE: Hibbs and I seemed to have stumbled into a “dueling banjos” type situation with these columns this week, along with commitments to more frequent updates. This wasn’t intended, but it seems these changes have lit a fire under both of us.

If you want to see this kind of thing happen LIVE, then keep you calendar clear for this coming Monday…

On Monday Sep. 27th at 7PM, @Comixace, @anthonyha and I will be talking about the state of comics retail with @savagecritic and @soupytoasterson, live on Twitter Spaces. https://t.co/kHcrmC1HdZ pic.twitter.com/tIuKPPDMG1

— Brian Heater (@bheater) September 14, 2021

I don’t have time today to read this until full but you are echoing things I have been thinking for some time just from skimming. You should check out the book Of Comics And Men as it is a great history lesson behind the rise of comic books from their beginnings in the 1920s through 2010.

I feel the DM day has set even though it isn’t dead yet. The newsstand system only lasted about 50 years so am not surprised the DM is in the era it is. Natural evolution of readership is happening again and how we consume comics will continue to evolve. The next 5 to 10 years is going to be a wild time. A form of the DM will likely survive but it will not be what it was in the 90s or 00s ever again.

Will be following your articles with great interest.

Congrats on the new series!

I’d draw one distinction: where you divided overall comics units sold by SKUs, comics units by distinct comics releases (merging all covers) obviously yields higher numbers (in 2019, around 15,500 copies per release). A per-project count means more for publishers, while for retailers, SKUs are obviously a more relevant metric, in that, as you stated, it relates to processing and handling times.

That said, it’s undeniable that for a significant portion of the retail base, having more SKUs is something that makes them more money. A nuisance for a store that does not participate in the aftermarket can be a profit center for one that does — and in many cases, as we know, the shops themselves are funding the creation of their own variants. Viewed by those stores, a smaller number of copies per SKU in the greater universe might not necessarily be a negative thing, as long as it’s transformed into more dollars at the other end. Markup is something the Comichron/ICV2 annual report pointedly doesn’t track, so that portion of the periodical business will always be underreported.

We do already know that periodical sales are very definitely booming in 2021, even as graphic novels are. My estimates had pointed to that earlier in the year, but Diamond’s numbers in June and July confirmed it. Barring some major event (and we’ve seen major events lately!) I can’t imagine that the 2021 periodical dollar figure will be anything but up in the next annual report.

As you contemplate the death spiral of single issues, consider Japan.

How have current distribution methods affected the weekly sales of the huge phone books that once fed the entire manga ecosystem?

Over in German, Micky Maus Magazin was once a million-plus readers weekly, sold almost exclusively from newsstands. Now? 405K, biweekly.

And, of course, what will comics shops look like 10, 20 years from now?

Do they revert to the pre-comics magazine dealers selling old copies of Life and other paper ephemera, a giant room filled with back issue bins?

Do they become specialty booksellers?

Do they become hobby shops and/or pop culture retailers, selling physical goods aimed at casual fans and hardcore aficionados?

Looking forward to future columns, Brandon.

Anecdotally, my experience discussing comics with an older coworker regularly circles back around to the single issue vs trade paper back format topic.

He stands solidly on single issues whereas I favor TPBs and I generally attribute that to nostalgia. Where he grew up saving weekly allowances to visit newsstands and pickup his issues, gradually evolving into purchaing directly through individual distributors, my experiences have been rooted in purchasing from secondary and used markets where its possible to get more bang for your buck with TPBs. Added to that, the ability to avoid the additional 10 – 15 pages of advertising is a huge draw for purchasing consolidated volumes over single issues for me.

Financially, he could, like your ‘Uncle Frank’, sell a handful of first issues from his collection and buy my entire library of TPBs, but I enjoy the ability to hand off a whole volume (or series) to friends or nieces and nephews and not have to give them detailed instructions on how to avoid handling wear and tear. Being able to easily share great stories from my hobby is a huge plus and has helped me pass my love for comics on to others.

Looking forward to the next column!

Comments are closed.