When moviegoers took a chance on this new ‘killer with a knife’ movie that had just come out on October 25, 1978, aptly called Halloween, they were treated to a rare example of experimentation that would catch audiences completely off guard. It opened with a first-person view of someone outside a house, looking in on a girl and her boyfriend as they took advantage of the fact there were no adults around. This person walks into the house, picks up a knife (showing small kid hands seemingly dressed in a clown costume), hides to let the boyfriend leave after what was a worryingly brief sexual encounter, puts on a mask, and then goes to his sister’s room where we learn his name is Michael and that he intends to stab his sister to death.

This wasn’t a giallo movie where the audience was allowed moments of voyeur when the camera moved to the killer’s point of view, an important creative decision in its own right that would define a unique style of horror filmmaking. This was an introduction to the story’s monster, Michael Myers, and we had all been invited to witness his first kill. The rest is history.

The monster’s POV shot is not an entirely uncommon occurrence in horror. Movies like Deep Red (1975) and Friday the 13th (1980) are but two examples of works that have employed this style to great effect, especially in how they set up death sequences. Then we have An American Werewolf in London (1981), which kept the wolf largely hidden behind the camera, with only flashes of it throughout that helped build up anticipation for a finale where the monster was finally allowed to be in front of the camera. Predator (1987) would stand out by showing the titular creature’s unique ability to hunt using heat vision, which we also got the chance to see in first-person. The PS2 video game Siren (2003) would take things a step further by allowing the player to “sightjack” the ghosts that follow the main character for brief periods of time.

The keyword here is brief, and all its synonyms. These movies would dip in and out of their POV sequences for moments at a time. The effect could outstay its welcome if used too much in one sitting. Two recent movies, though, have taken it upon themselves to prove that this approach can remain effective for the entirety of their runtimes, Steven Soderbergh’s Presence and Chris Nash’s In a Violent Nature, and they’ve extended an open invitation for fresh new takes on POV horror.

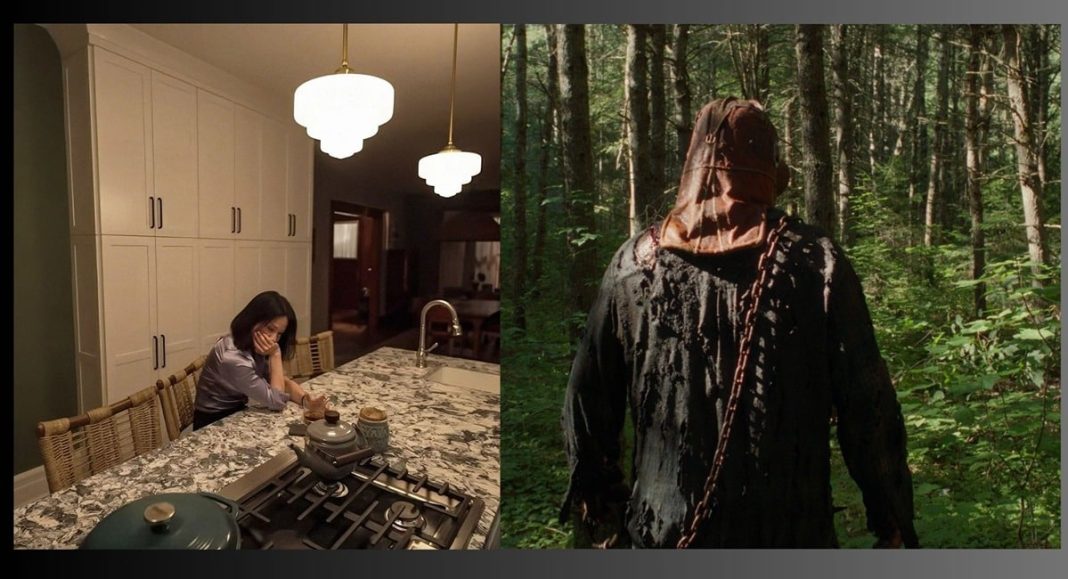

Presence takes the POV of a ghost haunting a house. A new family moves in and immediately begins airing out their dysfunctional ways in front of this invisible entity. The ghost reacts to them accordingly, moving things around and showing its anger when it deems it necessary. In A Violent Nature follows a Jason Vorhees-like slasher as he stalks a group of archetypal, young victims in the woods. We learn a bit about the supernatural killer in snippets of lore that are dropped here and there. The camera hovers a short distance behind the killer for most of the movie, meaning we get to see the back of his head a lot. Kills feel more brutal because of this. They’re uncomfortably close to the camera and go hard on the method behind the slasher.

Both movies find ways to quell worries about the new form rather quickly. One of the main worries about In A Violent Nature, for instance, was that it would end up being boring. What could Jason actually be doing when he’s not killing? Standing behind a tree waiting for a horny teen to walk by? While it does have a lot of walking, Violent Nature does manage to keep things interesting with the slasher overhearing conversations, or taking his mask off in a way that’s used to build upon the character’s myth.

Presence is also never boring. The ghost is always on the lookout to get a better sense of the family it is haunting, and it stays distressingly close to each member as they talk about some of the most personal and painful things they’re going through. There’s intention behind the ghost’s eavesdropping. It’s as if the ghost is studying them, aware of the idea that the family might actually be haunting it.

While both these movies do several things right, I hope that they inspire more movies of their kind that address their shortcomings. For example, Presence doesn’t have a particularly potent scare factor. It’s more a family drama that’s experienced from the POV of a disembodied third party. In fact, the way some of the family drama scenes play out, you forget you’re seeing anything through the eyes of a ghost. It often looks like a regular movie with fancy camera work. It’s a missed opportunity, and a very disappointing one because the movie could’ve easily committed to exploring the mechanics of the haunting and what a spirit does to make its presence known as it had all the necessary elements to do so.

In A Violent Nature, on the other hand, follows through with its concept, but it sidesteps one of the supernatural slasher’s most mystifying abilities: teleporting long distances for a kill. Michael Myers, Jason, and countless other 80s slashers have been known to come out of nowhere after having been shot, stabbed, or pushed off the roof of a house to catch their victims as they’re running away from them. The only one that leaves no questions unanswered on this matter is Freddy Krueger because he stalks his prey in a dream world, where he can manipulate anything to his liking.

Director Nash simply shies away from this for an extended car ride scene that betrays the POV concept by latching the camera onto the slasher’s remaining victim. To a point, it’s as if he didn’t exactly know how to explain it and so decided not to. The movie does try to leave this aspect up for open interpretation, with a final shot that puts the burden on the audiences to conclude whether the slasher is close by or not despite the impossible distance between him and the victim. But this wasn’t the time to hold back. It was the moment to go all in to potentially give us something special.

That said, I’m glad these movies exist. They’re both door openers with big neon arrow signs pointing to the entryway. The possibilities are endless, and it’s up to upcoming filmmakers, seasoned filmmakers, and everyone in between to give it a shot. The POV shot doesn’t have to be an identity concealer anymore. Now, for the price of a movie ticket, you can become the monster, and you’ll get a taste of what it’s like to be the thing others run away from.