Gory horror comedies can be tricky to pull off, especially given their propensity to go into mindless slapstick territory and stay there. When they work, though, they allow audiences to seamlessly mix in screams with laughter to create unique takes on horror. Peter Jackson achieved this with his films Dead Alive (also known as Braindead, 1992) and Bad Taste (1987), both gleefully violent movies that find humor in exaggerated forms of violence (in Dead Alive a priest uses his karate skills to fight decaying zombies with easily detachable limbs). Sam Raimi did it with Evil Dead II (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992), building up his Ash character as one of the funniest badasses in the genre. Osgood Perkins has his own great horror comedy in The Monkey, in which death just piles up in spectacularly gory ways.

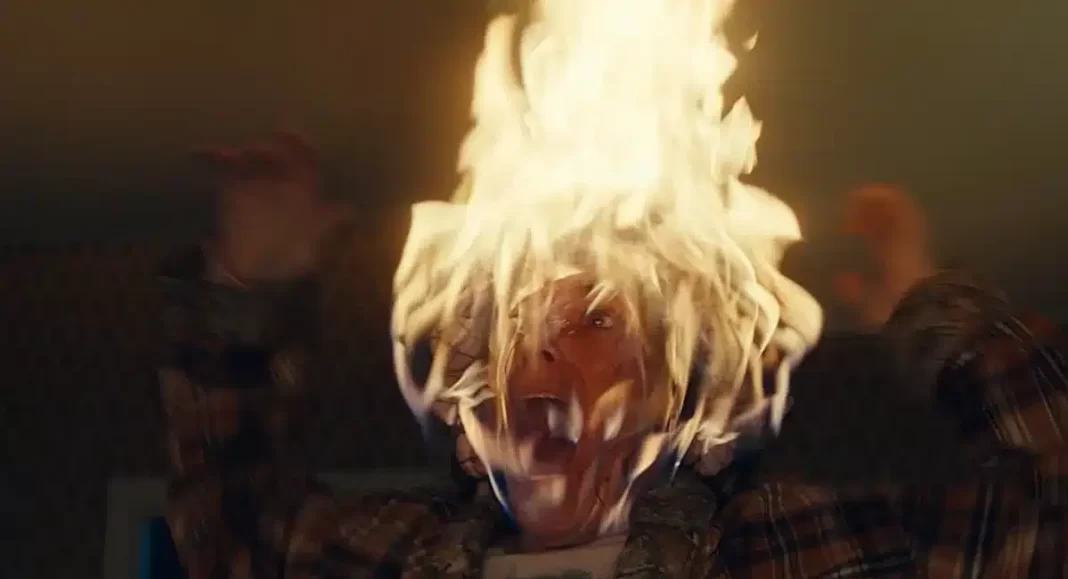

One of the main reasons why The Monkey works is because each of the many deaths that occur onscreen are expertly crafted and shot to make the funnier bits shine through as explicitly as it can. A great deal of this is owed to the movie’s VFX supervisor Edward Douglas and his team. They all managed to craft a series of deaths that borrowed more from the Looney Tunes rather than Lucio Fulci (though he would’ve been proud of what he saw had he been around for it), but with an eye to incorporate both styles of violence.

The cartoonish elements here are injected with generous doses of blood that guarantee continued shocks to the senses throughout. If Elmer Fudd shot Bugs Bunny in the face in The Monkey’s world, his features would be completely rearranged so that skin flaps, brains, and broken bones would get the punchline across. There’s not a wasted death sequence in sight in The Monkey, which means Douglas and team had plenty of canvases to experiment with to make them as gruesome as possible.

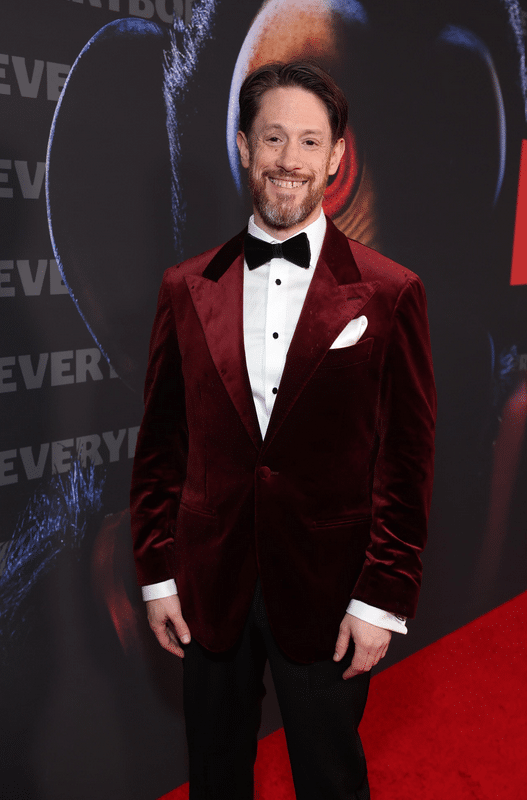

The Beat sat down with Edward Douglas (whose work includes the video game Mass Effect 2 and Need for Speed: Most Wanted) to talk the mechanics of making death funny and how it differs from the way violence is shot in more serious projects.

RICARDO SERRANO: There are a few key differences in tone and violence to be found in the original Stephen King short story the movie’s based on. That said, how did the source material influence the look and feel of the big screen version?

EDWARD DOUGLAS: My leaping off point was Osgood Perkins’ script, at every point. This is an Osgood film. It’s his adaptation and it shows how his love for the King story, and he’s spoken on record about how he wanted to evolve it and put his own stamp on it. It’s a dark film and it’s a hilarious film, this last part being different from the source. But everything we did was based on Oz’s vision. It really grounded us in terms of how to support him and help him create the film he wanted to put out there.

SERRANO: You worked with Perkins before, on Longlegs. How do those two experiences differ? Was there a shared language there you fell back on?

DOUGLAS: We absolutely had a shared language on The Monkey. But it was also an evolution of our work together. And it wasn’t only like this for me. Most of the Longlegs crew moved on to The Monkey, from producers to our assistant director to our production design team and the props team. Even though this one is a very different film tonally, it’s still very much an Osgood film. We were able to continue close relationships while nurturing the language we shared beforehand. That he wanted to come back and do another film with the same people was an amazing show of trust for us.

He did establish what was different. Longlegs was a dark, ominous, brooding film rooted in satanic horror and things like The Silence of the Lambs. It’s a procedural, and there’s not one bit of any of that in The Monkey. He was very clear early on about tonal references and one of the guiding ideas here would be Looney Tunes. It also had a bit of Gremlins in there when it came to excesses and the gratuitousness, but I remember he had talked about how he wanted it to feel like a 1980s Robert Zemeckis film on acid. The number of times we talked about the blood and guts cannon was absurd. At one point we discussed how much blood actually fits in one person. In this movie, it’s at least three times the amount.

SERRANO: How did this figure into conversations about practical effects vs. CGI? Was one style better suited to the story or was the combination necessary to get the most out of the concept?

DOUGLAS: There was never a conversation about practical versus CGI. It was always a conversation on what is the most effective tool to create this moment. Often for me, it’s about understanding the vision of the shot or sequence while working with the director and the script at the same time. It’s finding the most effective and the most efficient way of creating a particular scene that achieves the goal. And sometimes that means we’re going to create something on set that will go for a lot of the distance. We then add or combine pieces together in visual effects later to achieve what we visualized.

For me, visual effects for The Monkey was about looking at the things that could happen, making them ridiculous, and then figuring out how to do them with buckets of blood and gore. We’re here to help tell the story for the director when it comes to things that are impossible, impractical, too expensive, or too unsafe to film. If we want people to run around with their heads lit on fire or their bodies falling apart, we need to weigh our options and get creative.

SERRANO: It sounds like being a VFX supervisor is kind of being an orchestra conductor. You might go “blood on this wall, body parts falling down from up there.” Is that how you see it?

DOUGLAS: I always feel like I’m helping someone tell a story. I do like the idea of orchestration. You really are dealing with multiple moving parts while trying to figure out how to achieve what is impossible to film for real. This means working with every department, the director of photography, the production designer, the special effects team, the stunt team, the editor, and the producers. Sometimes there are things that we would love to film for real, but it doesn’t make sense practically or we know that if we can achieve it and make it look good with enough visual effects, then we do the more sensible one (or not). Sometimes it’s about how to show better use of our resources rather than, say, building an enormous set that we may only see once in the entire movie and only very briefly.

Every film brings its own challenges, and that tells you how you’re going to be working with the team. A lot of my job is helping everyone visualize what the end product will be. That could be through storyboard, concept art, anything really. We then make sure all the pieces are in place. My background is actually in cinematography. I then moved into virtual cinematography and virtual storytelling in video games. Those experiences all made me see every single thing available to me as a potential tool, a resource I can use somewhere to do my part in building a larger narrative.

The Monkey is now available on VOD.