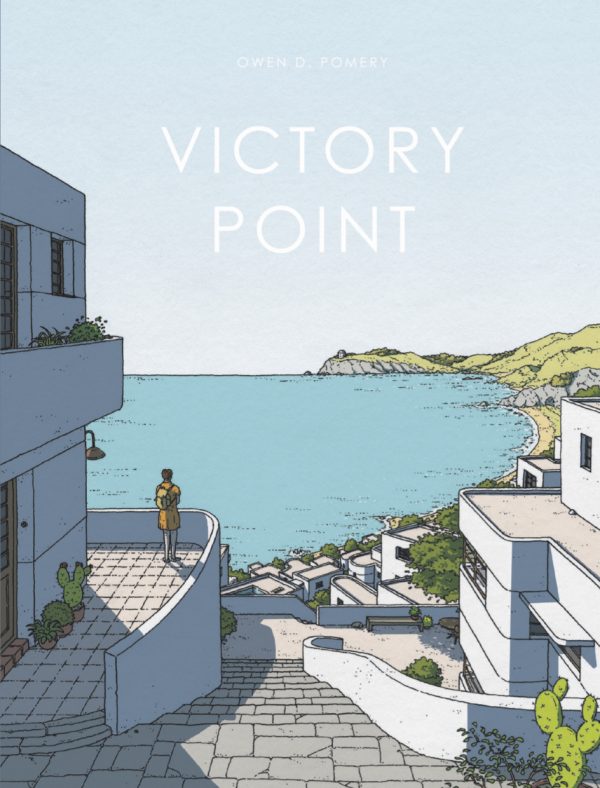

Victory Point

By Owen D. Pomery

Avery Hill

Most people live small lives. By that, I’m not referring to the importance of the lives, but rather the visibility. These lives don’t broadcast or even scream. They don’t attract attention in general. As such, the changes that come to them are often achieved through an unassuming process that doesn’t get noticed and doesn’t hold a press conference that it’s taking place. The process is internal and the results might be impactful of an area larger than the small life itself, but typically the person who is the object of the result is usually overshadowed by it and happy to be so, and the impact can be described as local in geographic, political, cultural, and psychological terms.

That’s the kind of life that Ellen lives in Owen D. Pomeroy’s Victory Point, an unassuming little book about quiet goals and humble plans amidst the enormity of where Ellen comes from, itself a collection of the same.

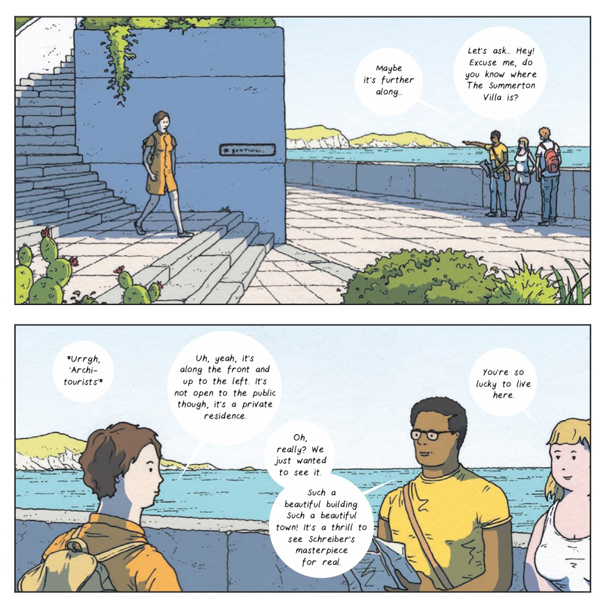

Ellen lives in London, works in a bookstore, and one day takes a train to her hometown to pay a visit with her dad to check on his well-being. Almost immediately Ellen runs into former schoolmate Gemma, and a quick catch-up illustrates how out of sync Ellen feels in Victory Point and with the people she knew there. That’s possibly a result of the way the town appears and how that represents the stunted quality Ellen feels there — chosen as the site of an architectural makeover in 1933, Victory Point was to become a modernist vision, though the effort was cut short. With one-third of the village transformed and the rest the same as it had always been, Victory Point became a tourist oddity and tangible manifestation of the inability to move forward completely. Victory Point is a monument to hesitation.

That may not entirely be true, though. The rest of Ellen’s visit consists of more interactions with a variety of people, including her father, and each gives a perspective on what being in Victory Point means to the person Ellen encounters. For some staying there is just what you, for others you go seeking an oddity, an aberration, and you may just find an answer with that. For her father, Victory Point is a place with an emotional connection where he happened to end up. You can never predict where emotion will take command of your daily life and wrap itself around you. As Ellen talks about her life working in a bookstore and relates her dreams and goals in the context of her current existence, she has trouble envisioning a way forward, but the mistake she makes is to assume that everyone in Victory Point stays put because they can’t think of any other choice.

While most of us live small lives, it sometimes feels as though there aren’t stories small enough to depict them correctly, but of course there are, and Victory Point is one of them. From Pomery’s calm, polite dialogue to the depth that the conversations reach to the way he draws Ellen’s wanderings around Victory Point, this is a small book in the best possible sense. There’s so much silence around the quiet, with the cold grandiosity of the village architecture taking control of the panels as Ellen walks around, matched by a secluded beach and a grassy cliff with an unassuming observatory on it.

Actually, that observatory is the key to the story in many ways, but its quiet is deceiving. It’s proof that there is sometimes drama to be had, but that the bombastic moments are fleeting and even if we try to keep the emotion of them alive, they only really resonate inside us. And they do so during our small life, which can’t help but contain their larger impact and make them something more manageable, something that fits us rather than overtakes us.