By Sara L. Jewell

Andrea Shockling is an artist based in Pittsburgh and Astoria. She’s worked on Broadway and in regional theatres and universities across the country as a painter, scenic designer, and educator. Now she mostly works for herself.

Her hand painted and mosaic murals can be seen in businesses and homes in California, New York, and Pennsylvania, and her artwork and graphic design has been featured in traditional gallery shows, regional magazines, corporate publications, and on websites.

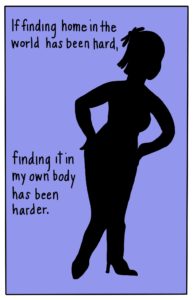

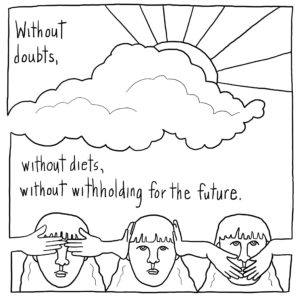

For the last few years, Shockling has been working, often collaboratively, on the comic series Subjective Line Weight. This comic is “an ongoing project featuring women from all over the country sharing stories we’re not often supposed to tell: fears and failures about our bodies, the shame of weight gain or weight loss, societal expectations of beauty standards, eating disorders, extreme (and expensive) lengths we go to in order to feel beautiful on the outside while neglecting the inside.”

In addition to collaborating with other creators on Subjective Line Weight, Andrea Shockling also makes memoir and diary comics. At New York Comic Con 2019, The Beat sat down with Shockling to talk about her work, the appeal of comics, body representation in art, and more.

Warning: Parts of this interview — including images — discuss weight loss, dieting, and bariatric surgery, as well as body dysmorphia and eating disorders. If any of these topics are triggering, proceed with caution.

Sara L. Jewell: Alright, so I wanted to just start off with generally [asking] why you’ve chosen comics over other mediums — what appeals to you about them, particularly?

Andrea Shockling: So, it’s interesting because I came to comics after doing theater and I think there’s a tremendous amount that they have in common. They’re both collaborative. They both sort of use visual moments to enhance storytelling; obviously, in theater, you have like the temporal aspect, but you still talk about the environment. You talk about the world-building. You talk about the stage pictures, and I think that there’s a lot that comics and theater have in common in terms of vocabulary.

So when I stopped doing theater I was still looking for an outlet for storytelling, and comics was an obvious choice because I’ve always been a comics reader. I was familiar with the medium but it seemed almost like… storyboarding would be like the kind of connective tissue between those two. It seems like a very kind of obvious step. And one of the first stories that I needed to unpack myself was dealing with after my mom died.

Jewell: [Was that] Mom Privilege?

Shockling: Yeah. So that first kind of grief-unpacking was a combination of words and pictures with a less sequential focus and more [of an] illustrated prose or poetry kind of comics style, you know, very typical in autobio right? Where the panels are not restrictive because sometimes there are no panels. But it was like a very raw form of expression. And I realized, like, wow, this is exactly where I need to be right now. And it just felt really comfortable, so that’s what I’ve been doing since. It’s awesome.

Jewell: You mentioned that you have been reading comics for a while. Do you remember the first comic you ever read or the first one you really responded to?

Shockling: You know, I’m — I’m 40. So like the early 90s stuff is kind of prime for me. I read … like all of the original X-Force. The early ’90s really spoke to the masses when it comes to comics and that, I think — for a lot of us — introduced us to at least the IP in the Marvel Universe that, you know, a lot of us are familiar with. But I also read Elfquest like way too early.

I had an under-the-table, helping-out job at a used bookstore and we got a bunch of Elfquest in and I was like immediately fascinated with this, because I had been really interested in and read a lot of fantasy prose. So, “Oh, here’s this comic and it’s not really kid appropriate — there’s a lot of elf sex.” Yeah but whatever, you know there’s also a lot of not-elf sex — stories and stuff. But I think it was an important comic to show me that comics were not just superheroes. It was probably the first creator-owned content that I was ever exposed to.

Jewell: I’d like to talk a little about your process making a comic. Specifically, where do you start? Do you start with the words, with the images, something else…?

Shockling: That’s a complicated question. I’m working on a graphic novel right now — a memoir about my mom. It’s what Mom Privilege has morphed into. It’s called A Dangling Conversation and it’s being pitched right now. And the process on that was much more formal than I’m used to with my autobio stuff.

I guess I would say I have three sort of distinct processes. If it’s my autobio stories like Fat, the bariatric diary that I’m working on, I’m breaking the space down first, then the writing, and then the thumbnailing, which is a somewhat unconventional approach. If I’m working with somebody on Subjective Line Weight, I do an interview or we have a conversation and so I have, like, the written content, and I sort of thumbnail/edit the words and then move on to the pictures.

For Dangling Conversation, I did a full outline, which was a brand new process for me and an incredible learning experience because it absolutely forced me to make decisions earlier in the process than I would have. But because it’s such a greater volume of content, I needed that information sooner. Then I did traditional thumbnails and then I scripted. That’s why I need an editor, always, because if I’m working by myself, I have like multiple irons in the fire. And having a good freelance editor when you’re doing inventive stuff on your own helps you ensure that the process doesn’t get corrupted.

Jewell: So, you characterize your Subjective Line Weight comics as women’s “stories about our bodies we’re not supposed to tell.” While all of these stories situate the narrative in the body, there’s quite a variety present. Why are these stories all stories that weren’t “supposed” to be told?

Shockling: I think that most people have a complex relationship with their body and how it fits in amongst other bodies. And we as a society are not great at providing a forum for kind of reconciling your feelings about your body compared to others, yet that’s how we initially judge people. When I say judge people, it’s like the first thing that you see about a person is their physical body. And that sets the tone for many further interactions, be they positive or negative.

We don’t have a lot of control over the things that we’re given in terms of ability, disability, height, oftentimes weight, traditional standards of beauty… There are certainly extreme measures that you can take, you know, plastic surgery, etc. But by and large, we don’t have a lot of control over what we’re given, and yet it plays a tremendous amount of importance in our paths through our lives. And I think for women especially because the societal beauty standard is so pervasive — in advertising, in television, in all media! From a very, very young age, we are aware of how we do or do not conform to that.

We’re supposed to, like, “take one for the team” if you don’t fit in with those beauty standards, [and] you’re not supposed to question that. I realized that there are all of these stories that people have about their own relationship with their body or the way that another external relationship has impacted how they feel about their body, and we don’t make space for those feelings.

I would say that most of us are not extraordinarily beautiful, right, like the percentage of the population that is a supermodel is quite small. I would say that most of us struggle with feelings of inadequacy or feelings of not having the body that we should or that we want or whatever. And we’re not really allowed to acknowledge that; we’re just supposed to, you know, buck up or — or, we’re supposed to constantly be working towards the ideal. You know, either one is fine. If you’re not happy with your body and you just keep your mouth shut, whatever, but if you’re not happy with your body, you better be working on making it as damn close to the ideal as possible.

And there’s so many mixed messages and it’s so psychologically damaging, and the end result is that you don’t realize that everybody else around you is feeling similarly. One of the best results of Subjective Line Weight has been that more and more people come up to me or contact the contributors themselves and say, “I relate so strongly to this story. This same thing happened to me.” Or, you know, “here’s this similar thing that happened,” or whatever, because when one person is brave enough to step up and be like, “Hey, this is bananas and this is my story,” then you realize that it’s not normal, right? Like, it’s okay that you’re having some dysfunctional feelings about how you fit into the world, because it’s a complicated place and we don’t make it easy for people who don’t fit the ideal.

As affirming and relatable as these narratives are for people who are suffering from a culture of body shaming and selective body positivity, as well as the way that intersects with race and gender, do you feel like it’s also changing the minds of people who are perpetuating harmful ideas about what a healthy or attractive body “should” look like?

Shockling: That’s a kind of fascinating twist to what the expectation might be to sharing stories like this, like, “Who are you doing it for?” And right now my focus is on the voices of the people who have experienced that, like, trauma, essentially. That for whatever reason, their body wasn’t what it was “supposed to be” in a particular situation: they were too fat for a concert, they were too fat for a diagnosis, they were too male when they should have been female…

There’s so many of these extreme examples in these stories of like, not being the right thing at that time and I’m less concerned about the changing the minds part. Giving a voice to the feelings of women who have had those experiences is the first step, and making sure that those voices are counted has to come before any sort of sea change in the way that people treat one another or the acceptance of somebody whose body isn’t the norm. That’s a lovely goal, in the long term. But I think that we’re not there yet. And so I wouldn’t be surprised if somebody was like, “But well actually, you know…” There’s always going to be a response to a story… It could be, “Let’s listen to the other side.” You know, that sort of nonsense.

But I think that that’s a kind of lovely eventual place where we can actually change other people’s minds, through comics?! That’s awesome. The closest that I’ve come to that sort of thing is I’ve had many people thank me for being so candid about things that are hard to admit. So that’s a little bit different than giving voice to it. Like, most of the women who have said that are coming from a perspective closer to a traditional standard of beauty. They’re thinner or they’re prettier. I would say that the women who appreciate the new perspectives aren’t experiencing those things themselves, but I don’t think that those women needed much of a nudge — they didn’t need their minds changed. So not as much of a flip; it’s more about context.

Jewell: How did you end up connecting with the other narrators of the Subjective Line Weight comics?

Shockling: So, some of them are friends and then it was like friends of friends and then friends of friends of friends. It’s people who have read other stories and contacted me…it was really word of mouth. I have occasionally reached out to people and said, like, I would love to hear your story or love to help you share your story. But most of the time people contact me and say, I have something that I think fits this project.

I sort of put new stories on hold this past summer because I was focused on my own story. So looking ahead, it’ll be interesting to see what kind of new perspectives I can add to the collection, because there are definitely things that we haven’t touched on yet. But I’m also interested in getting back toward some of the original stories about fatphobia and things like that, that kind of reflect my own feelings about that issue in particular.

Jewell: You write in Subjective Line Weight’s introductory comic about the body as a “locus of control” — is that a theme you’ve seen re-emerge with your collaborators?

Shockling: Yeah, absolutely. There’s a definite connection between your body health, and your mental health, and your environment health. Anecdotally, I feel really strongly about the transition that I’m going through and what I have in my capacity to control and how wide I can make the ripple effects around me. The wider that I can make that, the less anxiety I have. But I feel like that connection is something everybody probably experiences.

But the access to make those controlled changes diminishes when you don’t have, like, thin privilege or you don’t have health privilege… anything that is making your day-to-day existence more complicated. If you have a physical disability or a mental illness, your ability to affect change is going to be less. Each one of the women I have spoken with so far has been at a transition point or has recently completed a transition, and has seen both how her body can affect change and how she can affect change on her body. And I think of that transition as more of the through line.

Throughout our lives, our bodies change tremendously. When you take a single moment and you really look at your body in that moment: what control do you have over it and what control can you influence for moving forward with additional changes? I think that the story of our bodies’ transitions is the through line with all of this.

Jewell: Something that really impressed me in looking through your work is even just within Subjective Line Weight, you really change things up a lot in terms of your visual style. There are really distinctive approaches to each of these comics and even reading some of your other comics, there’s a difference — not necessarily in terms of polish, but in detail and fluidity. How do you develop each of these comics visually to achieve a distinctive style?

Shockling: One of the things I used to do with Subjective Line Weight is to look at tone or the environment of a story and pick a style that helped push that narrative. I mean, the obvious example is there’s a story in the first volume from a dancer talking about an eating disorder and it’s done in the style of Degas. That was a fun exercise, but I think ultimately less successful as a comic. I have mixed feelings about that because I sort of love the different approaches to Subjective Line Weight, especially in the first volume, and some of the later stuff has become too reliant on a “house style.” So then I said, “Wait a second, they’re looking too similar,” and I kind of went back to that approach.

So one of the later ones that I did was a very visceral story about body dysmorphic disorder that’s a little bit gross — well, grotesque, I think, is a better word for it. I was initially hesitant with that case to share it with the contributor, because I didn’t want her to feel ugliness from it, but it was a difficult topic. But she loved it. She was like, “This is exactly it, this is right from my mind.” So, in that situation, it was a little bit collaborative. A lot of the other ones are not.

One of the beauties of Subjective Line Weight is that most of the time, I’m not working with comics creators. There’s a couple of exceptions, but you know, people who are not writers or who are not comics people are going to just be like, “This is awesome! Thank you! “So when I have this little nugget of potential collaboration, I love that. That makes it even more fun.

But I think the different styles goes back to finding the right tone. It’s almost mini world-building for each story, but it’s about the tone and it’s about the color palette being somewhat limited. It’s about the shape of something being more prominent. So it has, I think, evolved from just being something like, “It’s dancers, so let’s do Degas” into something a little bit more sophisticated. One would hope.

Jewell: Are you reading anything in particular right now that you’re really enjoying? Or is there something you’ve recently read that you really recommend?

Shockling: Man. I picked up a couple of things from SPX, but because I know I’m still in this stage where I’m hand-selling most of my work, I’m very hesitant to leave the table and I end up missing out on all the awesome things! I have started but have not yet finished Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up With Me, and it’s delightful. I read Kiss Number Eight, which is really fantastic. I just finished Guts, which everybody should read…

So, I had gastric bypass surgery on August 9 and had this stack of books that was going to be part of my recovery, because, “Oh my goodness, I’m gonna be bedridden!” It turns out I wasn’t. And I was up and about like super fast and I haven’t gotten through my stack of books. So it’s sort of a yay-boo. Like, I’m thrilled I’m doing great, but I have all this really good content that I have to force myself to sit down and read. And it’s a weird thing to make comics and stay up on comics.

Jewell: So in closing, I’d love to hear what you’re currently working on, if you can talk about it, and anything else you’d like to add!

Shockling: So, A Dangling Conversation is a graphic memoir about my mom and a surprise discovery about her that I made after she died, and then my subsequent investigation into this part of her life that I knew nothing about. That’s being pitched right now and has been a big focus most recently. This fall, my goal with Subjective Line Weight is to recollect it and get it out for wider distribution. I think it’s at a pretty critical point right now where it can either just continue like [it is] into whenever, or it can actually ramp up and get wider exposure. And I would love for the latter to be where that project ends up. That involves doing some re-drawing and reconfiguring of some of the earlier chapters.

And then Fat, the bariatric diary, will be collected. There’s a publisher interested in that, which is super exciting but looking at when’s the end of that? Like it’s an ongoing thing! My six month surgery appointment is in February and I think that’s probably when I’ll do a final — at least thus far — kind of chapter, and and do some other reflecting on that whole process. I’m also pursuing a strong desire to continue doing nonfiction comics. And I would love to work with a writer, whether that is science or history, or…I have a love of all of that, but that that’s kind of my next dream step. I’d like to find a good collaborator for that.

Subjective Line Weight is ongoing at andreashockling.com, where Andrea also homes her other work. To keep up with Shockling on social media, follow her on Twitter or on Instagram.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Comments are closed.