By Gregory Paul Silber

The “Fighting Fascism in Fandom” panel at New York Comic Con on Saturday started with a disclaimer from moderator Diana M. Pho reiterating NYCC’s anti-harassment policy. She also warned that direct confrontation harassing the panel would be met with “staff taking any action they deem appropriate, including expulsion from New York Comic Con with no refund.”

It may sound like a harsh way to begin a panel at a comic book convention, but in this case, it was appropriate. Unfortunately, as many members of fan communities, especially those from marginalized backgrounds, know all too well, fascist hate movements like Gamergate and Comicsgate have been growing within “geek” spaces and fandoms for years. Those who speak out against bigotry are often targets of harassment, so firmly establishing that such ideology was not welcome, and that such behavior would not be tolerated, was necessary.

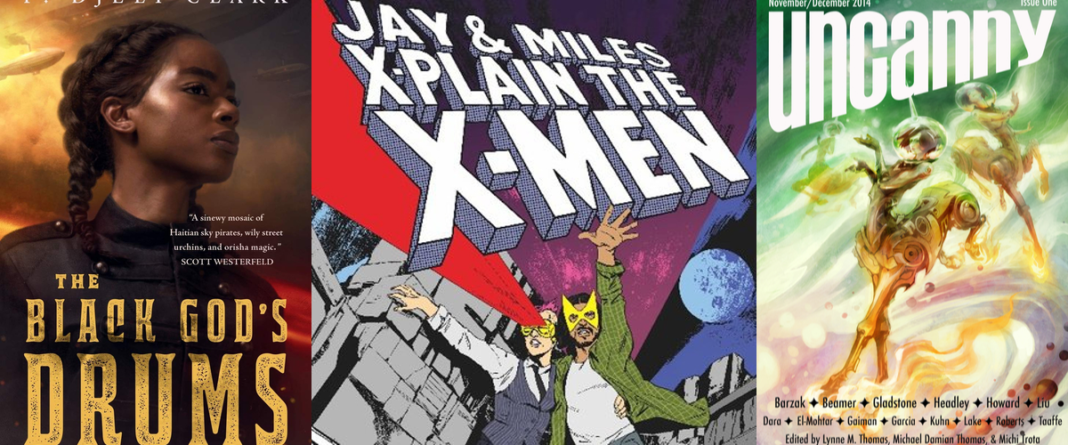

Pho followed the initial announcement with an apology that “we live in the dumbest timeline,” and the shift to levity was met with laughter from the audience and panelists. These included New York Times bestseller and Nebula Award-winning author P. Djeli Clark, writer and Jay and Miles X-Plain the X-Men podcaster Jay Edidin, Hugo Award-winning writer and editor Mimi Mondal, Hugo award-winning author and disability advocate Elsa Sjunneson-Henry, and author and mental health advocate Zin E. Rocklyn.

Pho kicked off the discussion with a definition of fascism, and asked the panel why “fandom language” has become a conduit for it. Edidin claimed that beyond being a conduit for fascism, fandom helped shape the way fascism operates today, with Gamergate creating “the alt-right and fascism playbook.” He further explained that fandom has long been an organizing force for uniting people separated geographically with shared interests. This could be a force for good, however. He cited Star Trek fandom as the first major fandom movement, an early celebration of a “fundamentally political” piece of fiction.

Sjunneson-Henry explained that fandoms can help bring together people who feel like outsiders, another positive element of these communities that can manifest in harmful ways. Edidin added that “symbols and points of identification” offered by fandoms can also be appropriated in powerful ways.

Rocklyn said that “colonialism and white supremacy has been part of our world for the last 500 years,” so marginalized people are now demanding spaces that were denied to them “by white supremacy, and not by merit… to be very honest with you, straight white dudes are feeling victimized, because their inherent power in white supremacy is now being challenged.” She added that they’re “scrambling to get their power back,” which has “warped” into fascism. The internet helps bring them together through sites like 4chan and 8chan and “Pepe the Frog, for which I’m glad that the creator sued.”

Clark described how from a historical perspective, “destroying fascism became a thing, right? But we also made it cartoonish.” It became such a symbol of evil in fiction like Hogan’s Heroes and Star Wars that he wondered if we “lessened the threat.”

Chu suggested that “we made it too easy. Too obvious… too black and white. ‘Nazism is bad.’” Yet when it comes to fandom, it’s not always so obvious. Fascism “crept in” on fandom, and by the time we realized, “it was too late.”

Mondal also believed that it’s been “harder to notice fascism.” Sci-fi and fantasy fans often already see themselves as outsiders, so they’re “already rebelling against the mainstream.” She compared it to her youth in which she developed an interest in rock music. “It’s so hard to distinguish abuse from people who are rebellious in that community… there was some sexual harassment that went on in that community, and you could not talk against it, you sounded like a conservative. Or it was made to sound like you were being conservative.”

With the definition of fascism discussed thoroughly, Pho asked the panel how one might define anti-fascism. Sjunneson-Henry quickly and firmly provided her definition: Radical unabashed inclusion of people from marginalized backgrounds of a wide variety. That includes disabled people. That includes people of color and queer people. That includes Jews. That includes Muslims. You include everyone so that it isn’t possible to shut people out.” This was met by applause.

Edidin agreed, adding that spaces need to express these principles “clearly and explicitly from the start.” He added that “some of us respond by trying to find people to be better than. Some of us respond by trying to find ways to include everyone.”

Rocklyn said that it’s important to remember that “white people listen to white people… white people do need to speak up. When you are seeing symbols of oppression toward marginalized folks, you need to say something. We as marginalized folks have had enough of talking. We will aggressively make sure we are inclusive in spaces but at the same time, white folks talk to white folks. You need to reach out and understand not only that fascism is growing, but it’s growing from a system of white supremacy that has always been there, and white supremacy is not just for white people. I need people to understand that because white supremacy can be carried out by anyone who would like to align themselves as close to whiteness as possible.” She used the example of Latinx people “voting for Trump and wondering why they get deported.”

Clark said “I’m not going to debate my humanity with people… it’s not going to happen. You’re wasting your time. He went on to explain how fascists often persist by “denying who they are.” We need to expose them because “they’re gaslighting us.” This needs to be called out before it gets worse. He used the example of medievalists getting hijacked by white supremacists. “It’s been there all along, but it’s also been festering.”

Chu suggested that he might be “an optimist,” but naming fascism is important, and so is education. He returned to Rocklyn’s example of the “Latino guy waving a Trump flag who gets deported. He didn’t quite think this through!” He added that “a lot of these guys lob onto the aspects of fandom and society that accept them… how do we reach these people?”

The panel followed up this discussion by clarifying why these questions remain important. The consensus was that the onus should not be on marginalized people to have to continue asserting their humanity, as they can’t change who they are. People from more privileged backgrounds need to do more to educate themselves, and if they find themselves at fault, even accidentally, they need to work harder to own up to their mistakes. At the same time, the well-being of marginalized people pushed out of fan communities do to mistreatment should be prioritized over rehabilitating the reputation of the people who harmed them.

This reads like North Korean propaganda. Lack of pics tells me the panel was probably delivered to a largely empty room.

Comments are closed.