[Previous chapters: Introduction, 1 – Prehistory, 2 – Marvelman Rises, 3 – Marvelman Falls]

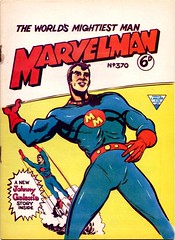

The Miller family received a major setback in 1966 when Leonard Miller, the company’s founder and namesake, died at the comparatively young age of sixty-seven. From that point on his wife, Florrie Miller, took over as managing director, although the company never produced any more comics, having in 1963 sold the asbestos printing plates for a lot of their comics to Alan Class Comics, another London based comics publisher, also specialising in American reprints. However, it seems likely that the Marvelman work was not included in this deal. The Millers found themselves with another setback in 1970 when they were prosecuted under the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955, for distributing certain American horror comics. The irony of this was that it was partially due to the Millers themselves, particularly Arnold Miller, that this act was brought into being in the first place.

In it, he drew attention to a ‘recent comic’ issued by the Arnold Book Company. Entitled Haunt of Fear, it ran to only one edition in Britain. This comic was the one most quoted in the entire British campaign, along with a related publication, Tales from the Crypt. (Indeed, when the Home Secretary strode to the dispatch box to introduce the Bill’s second reading on the 22nd February 1955, he borrowed a copy of the latter to carry with him.)

[There’s a larger version here, if that’s too small to read.]

Lord Mancroft, Under Secretary, Home Office, moved the second reading of the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Bill.

He said that at the request of Lord Jowitt he had put examples of horror comics, with which the bill was solely concerned, in the library of the House, and peers who had examined them would share his astonishment that anyone should want to read such boring, uninteresting nonsense. But their views were not shared by a large readership who were undoubtedly harmed by them.

[…] Earl Jowitt said that at one time six specimens of horror comics were placed in the library, but when he went there this morning, only three were left. (Loud laughter.) He had studied them and never in his life had he come across more disgraceful, discreditable, and abominable publications than those.

The names of the people responsible ought to be made public. One of the comics was printed by the Arnold Book Company of 2, Lower James Street, Piccadilly. […] He hoped that those persons were thoroughly ashamed of the publications they had issued. They were so thoroughly disgraceful that the House would be failing in its duty if it did not assist the Government to take steps to stop them.

The Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, 1955 was passed into law on the 6th of May, 1955 with the core of the act being this,

This Act applies to any book, magazine or other like work which consists wholly or mainly of stories told in pictures (with or without the addition of written matter), being stories portraying –

(a) the commission of crimes; or

(b) acts of violence or cruelty; or

(c) incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature;In such a way that the work as a whole would tend to incite or encourage to the commission of crimes or acts of violence or cruelty, or otherwise to corrupt, a child or young person into whose hands it might fall.

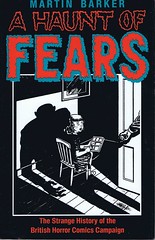

The act was originally due to run for only ten years, but it was renewed in 1965 and, to the very best of my knowledge, is still in effect today. There were various comic titles put forward to the Attorney General to be considered for prosecution as the years went by. However, in all those years, from 1955, when the law was first enacted, until now, there was only one case ever actually pursued under the act. This was in 1970, when L Miller and Co Ltd, along with a newspaper shop manager and a distributor, were successfully prosecuted for making a number of titles available to the public. According to Martin Barker in A Haunt of Fears,

Although various applications were made to the Director of Public Prosecutions, it is not clear when the first prosecution was made under the act. The Williams Report asserts that there were several successful prosecutions. However, it may be that the earliest was not until 1970, when L Miller and Co, the last survivor of the 1950s reprinters, was prosecuted at Tower Hamlets Magistrates Court for putting out a series of comics (part reprints from the 1950s, part newly and poorly drawn originals) called Tales from the Tomb, Weird, Tales of Voodoo, Horror Tales and Witches Tales. Because it was said to be the first prosecution under the 1955 act, Miller was fined only £25.

By 1972, it seems that the remaining Millers decided that the L Miller & Co (Hackney) Ltd had run its course. Florrie Miller was over seventy years old, and Arnold’s time was taken up with his film work. Len Miller, who founded the company, was six years dead, and the prosecution in 1970 for importing horror comics must have been a shock to them all. It was time to call it a day, and they decided to put the company into voluntary liquidation. Steve Holland, in a post on his excellent Bear Alley blog in November 2006, said,

The decision was made at a meeting of directors on 21 June 1972 and the company was officially wound up on 24 September 1974. […] It was a decision made by the directors (Florrie Miller, Arnold Miller and Doreen Lewis), debts and wages were paid off and the company was shut down.

And that was that. By the end of 1974 L Miller and Co (Hackney) Ltd was no more. Its property was sold off, and the plates for most of its comics had already gone to Alan Class Comics over ten years previously, when the Millers had stopped publishing comics. However, there still remains the question of what happened to the small quantity of original work that Miller commissioned, and in particular the question of what became of the rights to the Marvelman properties.

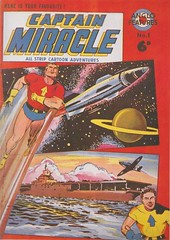

One thing is certain, which is that they couldn’t have remained the property of L Miller and Co, as the company was now no longer in existence, so – obviously enough – couldn’t own anything. And in all the intervening years since the company closed down in 1974, nearly forty years ago now, it seems that nobody has come forward with any paperwork or other proof to show they had bought or otherwise gained the rights from the Millers before they finished up. So, what became of the rights to Marvelman? Did any of the Millers decided to keep the rights for themselves? Did the rights somehow revert to Fawcett Publications in America, as the characters were a direct copy and continuation of their Captain Marvel characters, quite possibly with their explicit knowledge and agreement? Were they simply abandoned? Or did the rights belong to Mick Anglo and his company, Mick Anglo Ltd, who claimed to have taken a major role in facilitating the transformation of Captain Marvel to Marvelman?

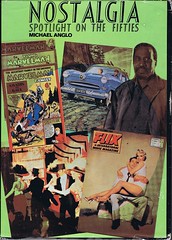

One possibility is that he knew that the Millers had wound up their company, and that the Marvelman properties were without clear ownership at this time, and took the opportunity, whilst writing about Marvelman, to add a copyright notice to the page of artwork he was including in his book. At that time, fourteen years after any of the Marvelman characters had last been published, and five years before Dez Skinn would revive the character in the pages of Warrior, he may have been the only interested party who had any sort of possible claim on Marvelman.

I don’t even know for sure when the copyright notice on the artwork was actually added, other than it must have been at some point between 1954, when the comic was published, and 1977, when Nostalgia was published, Although I’m inclined to think that it was more likely to be towards the latter year, rather than the former. And it’s worth bearing in mind that, when George Khoury asked Anglo about the ownership of Marvelman in 2001, he said, ‘I don’t know; that was Miller’s sort of thing’. If Anglo had wanted to claim the rights to the original Marvelman, this would have been the ideal time to have done so, with no other claimants in evidence, but he didn’t do so. His actions seem to show that he believed he owned some sort of rights, but he appears to never have unequivocally stated this in words.

So, who owned the copyright to Marvelman once L Miller and Co Ltd closed down? Was it Fawcett Publications, as the character was a copy of their Captain Marvel? Or perhaps Arnold Miller, who had been present throughout its heyday? Or Mick Anglo, who liked to tell the story of how he rescued the Millers from their dreadful crisis in 1953? Did DC have any claim, as Marvelman was a copy of Captain Marvel, who was a copy of their Superman character? Or was the copyright abandoned once the Millers closed down, leaving Marvelman in some sort of legal limbo, and therefore possibly in the public domain? Eventually, I’m going to attempt to answer some of these questions.

[The issue of the copyright notice on Young Marvelman #38 is covered in more detail in two posts on my own blog, if you’re interested: Marvelman Copyright: I Found My Smoking Gun and Marvelman Copyright: Same Comic, Different Gun.]

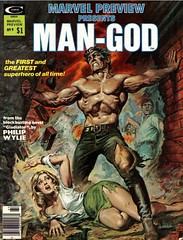

On the other side of the Atlantic, DC had continued to aggressively protect its most famous and valuable asset, Superman. In June 1959>MLJ Publications, publishers of Archie Comics, trying to get on the bandwagon of the Silver Age revival of interest in superheroes, had published the first issue of a comic called The Double Life of Private Strong, created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, which featured a character called Lancelot Strong, who fought crime under the name of The Shield. His father, a scientist called Dr Malcolm Fleming, had developed a method to create a superhuman by means of expanding the mind, a technique he used on his young son, Roger. After Roger’s father was killed by enemy agents, he was found and adopted by a farming couple called Strong, who raised his as their own son, and renamed him Lancelot. When he reached his teenage years, Lancelot discovered that he had unrealised super powers, like strength, flight, invulnerability, super vision, and so on. DC thought that this was all too similar to Superman’s origin and powers, and sent MLJ a Cease-and-Desist letter, and Private Strong never got beyond his second issue. However, it seems to me that the character’s origin owes at least as much to Philip Wylie’s Hugo Danner in Gladiator as it does to DC’s Superman.

On the other side of the Atlantic, DC had continued to aggressively protect its most famous and valuable asset, Superman. In June 1959>MLJ Publications, publishers of Archie Comics, trying to get on the bandwagon of the Silver Age revival of interest in superheroes, had published the first issue of a comic called The Double Life of Private Strong, created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, which featured a character called Lancelot Strong, who fought crime under the name of The Shield. His father, a scientist called Dr Malcolm Fleming, had developed a method to create a superhuman by means of expanding the mind, a technique he used on his young son, Roger. After Roger’s father was killed by enemy agents, he was found and adopted by a farming couple called Strong, who raised his as their own son, and renamed him Lancelot. When he reached his teenage years, Lancelot discovered that he had unrealised super powers, like strength, flight, invulnerability, super vision, and so on. DC thought that this was all too similar to Superman’s origin and powers, and sent MLJ a Cease-and-Desist letter, and Private Strong never got beyond his second issue. However, it seems to me that the character’s origin owes at least as much to Philip Wylie’s Hugo Danner in Gladiator as it does to DC’s Superman.

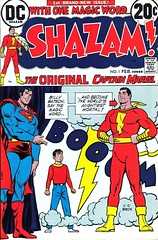

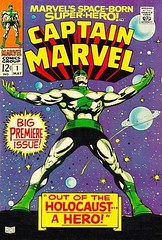

MLJ had published an earlier character called The Shield in the 1940s, which was eventually licensed to DC for their Impact Comics line, which ran between 1991 and 1993. Earlier on, DC had in much the same way licensed Fawcett’s Captain Marvel. After Fawcett ceased publishing Captain Marvel comics in the 1950s, they were left with a group of characters that they could no longer use, as part of the agreement they reached with DC stated that they would never publish those characters again. However, there was apparently no block on them licensing them to others, other than the fact that DC would go after whoever else published them, for the same reasons that they’d gone after Fawcett. Unless, of course, the company publishing them was DC themselves. And that’s exactly what happened in 1972.

In the summer of 1965 an eleven-year-old Alan Moore was on holiday with his family at the Seashore Caravan Camp in North Denes in Great Yarmouth, a popular seaside holiday resort on the coast of Norfolk which the Moore family visited every year (as seen in this photo shamelessly lifted from George Khoury’s The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore – that’s Alan on the right, with his cousin Jim), and he was looking for something to read. The distribution of comics in the UK at that time was, to say the very least, haphazard. While there were certainly regular weekly titles from publishers like DC Thomson and Fleetway Publications that could be expected to turn up when they were due, there were also lots of other old comics and annuals that would turn up in shops pretty much at random. There were distributors, like Miller, for instance, with warehouses full of old comics – their own, those of other small British publishers, and those that they had imported – that would be sold in job lots to newsagents, particularly in seaside holiday spots like Great Yarmouth, where they’d get bought up by bored children on summer holidays looking for something to read on rainy days, instead of going to the beach. And this is exactly what happened.

In the summer of 1965 an eleven-year-old Alan Moore was on holiday with his family at the Seashore Caravan Camp in North Denes in Great Yarmouth, a popular seaside holiday resort on the coast of Norfolk which the Moore family visited every year (as seen in this photo shamelessly lifted from George Khoury’s The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore – that’s Alan on the right, with his cousin Jim), and he was looking for something to read. The distribution of comics in the UK at that time was, to say the very least, haphazard. While there were certainly regular weekly titles from publishers like DC Thomson and Fleetway Publications that could be expected to turn up when they were due, there were also lots of other old comics and annuals that would turn up in shops pretty much at random. There were distributors, like Miller, for instance, with warehouses full of old comics – their own, those of other small British publishers, and those that they had imported – that would be sold in job lots to newsagents, particularly in seaside holiday spots like Great Yarmouth, where they’d get bought up by bored children on summer holidays looking for something to read on rainy days, instead of going to the beach. And this is exactly what happened.

This is how Moore described it to George Khoury in Kimota! In 2001,

I’d probably been about 11, and I’d gone on holiday to Yarmouth, which is a seaside resort in England, and I was looking for comics to spend my money on. Sometimes you get a different sort of comics turning up in a different town because the distribution system was much vaguer than it is now. I remember that there were a bunch of Marvelman annuals and for once there was nothing better to buy; I picked them up and I found them a lot more charming than I had remembered. There was something about them that I quite liked.

He hadn’t originally been a fan of Marvelman, however, as he says, again in Kimota!,

I think when I was around seven, which would have been 1960 – I’d have been six or seven – was when I saw my first American comics, when I saw my first The Flash and the first Superman/Batman comics that I used to pick up. It would have been around this time that I’d seen Marvelman. But Marvelman, even then, just seemed a flimsy imitation. These were sort of black & white flimsy, coloured, cheap little comics – although I didn’t know about Captain Marvel at the time, didn’t realize that Marvelman was a reinvention of Captain Marvel for copyright reasons. I think that I always kind of sensed that there was an inferiority to the product. I liked the idea of there being an actual British superhero, I just didn’t think that he was very good.

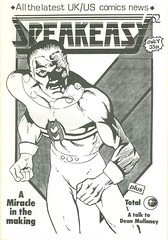

There’s a slightly different version of these events in an article called Miracleman: It’s a Miracle in Speakeasy #52 (ACME Press, 1985), in which Moore says,

In about 1966 I read some Marvelman album reprints and I knew a little bit about comics – I knew that Marvelman hadn’t been printed for about two or three years and that Marvelman had vanished… It occurred to me then ‘I wonder what Marvelman’s doing at the moment?’ three years after his book got cancelled. The image I had in my head was of an older Mickey Moran trying to remember the magic word that would change him back to Marvelman. If I had done it at the time, I would probably have done it as a Mad-style parody strip.

There was one other pivotal purchase at this time, as described once again in Kimota! ,

Around the same time I picked up one of the Ballantine reprints of Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad which has actually got the Superduperman story in it, and I remember being so knocked out by the Superduperman story that I immediately began thinking – I was 11, remember, so this would have been purely a comic strip for my own fun – but I thought I could do a parody story about Marvelman. This thing is fair game to my 11-year-old mind. I wanted to do a superhero parody story that was as funny as Superduperman but I thought it would be better if I did it about an English superhero. So I had this idea that it would be funny if Marvelman had forgotten his magic word. I think I might have even [done] a couple of drawings or Wally Wood-type parodies of Marvelman. And then I just completely forgot about the project.

Moore describes much the same version of events to Kurt Amacker in a September 2009 interview on Mania.com,

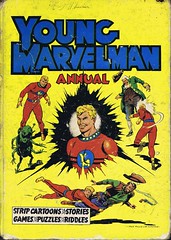

The origin of the [reinvented] character, as far as I was concerned, was, as a small boy I’d been visiting Yarmouth with my parents, which is a British seaside resort that we used to go to every year. And, I remember that the little seaside bookstores used to sell comics and books that would, presumably, have been on a different distribution circuit. And, sort of, you’d get titles turning up that you wouldn’t get at your newsagent and bookstores at home. I had picked up a copy of a Young Marvelman annual, which was a strange hard-covered thing that would be completely unfamiliar to an American audience. But, this was a collection of Young Marvelman and Marvelman strips by Mick Anglo. I also picked up a copy of one of the Ballantine paperbacks of Harvey Kurtzman’s brilliant Mad. It was the one that had Superduperman. Since I picked up these two things on the same day – and bearing in mind that I was 12 – it occurred to me that maybe I could do a brilliant parody like Superduperman, but of an English superhero. So, I started to imagine a kind of a parody of Marvelman, where he had forgotten his magic word. I don’t know where I was going to do this obviously derivative piece of work, and it never happened. But the idea did kind of lodge in my mind.

(The Mad reprint volume that Moore picked up was almost certainly The Mad Reader, originally published by Ballantine Books, New York, in 1954, and republished innumerable times since then. This is the volume that reprints Superduperman.)

My greatest personal hope is that someone will revive Marvelman and I’ll get to write it. KIMOTA!!

His wish was about to come true.

To Be Continued…

(As ever, you can find larger versions of all the images in this post here.)

In it, he drew attention to a ‘recent comic’ issued by the Arnold Book Company. Entitled Haunt of Fear, it ran to only one edition in Britain. This comic was the one most quoted in the entire British campaign, along with a related publication, Tales from the Crypt. (Indeed, when the Home Secretary strode to the dispatch box to introduce the Bill’s second reading on the 22nd February 1955, he borrowed a copy of the latter to carry with him.)

In it, he drew attention to a ‘recent comic’ issued by the Arnold Book Company. Entitled Haunt of Fear, it ran to only one edition in Britain. This comic was the one most quoted in the entire British campaign, along with a related publication, Tales from the Crypt. (Indeed, when the Home Secretary strode to the dispatch box to introduce the Bill’s second reading on the 22nd February 1955, he borrowed a copy of the latter to carry with him.) I’d probably been about 11, and I’d gone on holiday to Yarmouth, which is a seaside resort in England, and I was looking for comics to spend my money on. Sometimes you get a different sort of comics turning up in a different town because the distribution system was much vaguer than it is now. I remember that there were a bunch of Marvelman annuals and for once there was nothing better to buy; I picked them up and I found them a lot more charming than I had remembered. There was something about them that I quite liked.

I’d probably been about 11, and I’d gone on holiday to Yarmouth, which is a seaside resort in England, and I was looking for comics to spend my money on. Sometimes you get a different sort of comics turning up in a different town because the distribution system was much vaguer than it is now. I remember that there were a bunch of Marvelman annuals and for once there was nothing better to buy; I picked them up and I found them a lot more charming than I had remembered. There was something about them that I quite liked. In about 1966 I read some Marvelman album reprints and I knew a little bit about comics – I knew that Marvelman hadn’t been printed for about two or three years and that Marvelman had vanished… It occurred to me then ‘I wonder what Marvelman’s doing at the moment?’ three years after his book got cancelled. The image I had in my head was of an older Mickey Moran trying to remember the magic word that would change him back to Marvelman. If I had done it at the time, I would probably have done it as a Mad-style parody strip.

In about 1966 I read some Marvelman album reprints and I knew a little bit about comics – I knew that Marvelman hadn’t been printed for about two or three years and that Marvelman had vanished… It occurred to me then ‘I wonder what Marvelman’s doing at the moment?’ three years after his book got cancelled. The image I had in my head was of an older Mickey Moran trying to remember the magic word that would change him back to Marvelman. If I had done it at the time, I would probably have done it as a Mad-style parody strip. Around the same time I picked up one of the Ballantine reprints of Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad which has actually got the Superduperman story in it, and I remember being so knocked out by the Superduperman story that I immediately began thinking – I was 11, remember, so this would have been purely a comic strip for my own fun – but I thought I could do a parody story about Marvelman. This thing is fair game to my 11-year-old mind. I wanted to do a superhero parody story that was as funny as Superduperman but I thought it would be better if I did it about an English superhero. So I had this idea that it would be funny if Marvelman had forgotten his magic word. I think I might have even [done] a couple of drawings or Wally Wood-type parodies of Marvelman. And then I just completely forgot about the project.

Around the same time I picked up one of the Ballantine reprints of Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad which has actually got the Superduperman story in it, and I remember being so knocked out by the Superduperman story that I immediately began thinking – I was 11, remember, so this would have been purely a comic strip for my own fun – but I thought I could do a parody story about Marvelman. This thing is fair game to my 11-year-old mind. I wanted to do a superhero parody story that was as funny as Superduperman but I thought it would be better if I did it about an English superhero. So I had this idea that it would be funny if Marvelman had forgotten his magic word. I think I might have even [done] a couple of drawings or Wally Wood-type parodies of Marvelman. And then I just completely forgot about the project. The origin of the [reinvented] character, as far as I was concerned, was, as a small boy I’d been visiting Yarmouth with my parents, which is a British seaside resort that we used to go to every year. And, I remember that the little seaside bookstores used to sell comics and books that would, presumably, have been on a different distribution circuit. And, sort of, you’d get titles turning up that you wouldn’t get at your newsagent and bookstores at home. I had picked up a copy of a Young Marvelman annual, which was a strange hard-covered thing that would be completely unfamiliar to an American audience. But, this was a collection of Young Marvelman and Marvelman strips by Mick Anglo. I also picked up a copy of one of the Ballantine paperbacks of Harvey Kurtzman’s brilliant Mad. It was the one that had Superduperman. Since I picked up these two things on the same day – and bearing in mind that I was 12 – it occurred to me that maybe I could do a brilliant parody like Superduperman, but of an English superhero. So, I started to imagine a kind of a parody of Marvelman, where he had forgotten his magic word. I don’t know where I was going to do this obviously derivative piece of work, and it never happened. But the idea did kind of lodge in my mind.

The origin of the [reinvented] character, as far as I was concerned, was, as a small boy I’d been visiting Yarmouth with my parents, which is a British seaside resort that we used to go to every year. And, I remember that the little seaside bookstores used to sell comics and books that would, presumably, have been on a different distribution circuit. And, sort of, you’d get titles turning up that you wouldn’t get at your newsagent and bookstores at home. I had picked up a copy of a Young Marvelman annual, which was a strange hard-covered thing that would be completely unfamiliar to an American audience. But, this was a collection of Young Marvelman and Marvelman strips by Mick Anglo. I also picked up a copy of one of the Ballantine paperbacks of Harvey Kurtzman’s brilliant Mad. It was the one that had Superduperman. Since I picked up these two things on the same day – and bearing in mind that I was 12 – it occurred to me that maybe I could do a brilliant parody like Superduperman, but of an English superhero. So, I started to imagine a kind of a parody of Marvelman, where he had forgotten his magic word. I don’t know where I was going to do this obviously derivative piece of work, and it never happened. But the idea did kind of lodge in my mind.

now when i check the site and there isn’t a new one of these, i get sad.

From here on in, the plan is to have a new part online every Sunday. We hope…

Great work.

50s Britain seem to be very fast with laws and prosecuting literature which the government didn’t find suitable for the masses, not just in comics. Like the trial for the crime novels of Hank Janson.

But is the Harmful Publications Act really still valid? The idea that saner minds were at work a few decades later at the outrage for things like IPCs Action is nice, but seems rather unlikely. Which publisher would have risked a legal battle with the prosecution of Her Majesty?

Funny to think that Arnold Miller’s sex-pics have ended up getting DVD releases by the British Film Institute.

That brings back a lot of memories. In the 60s not only could you find things on holiday that you’d never see at home, but even back at home there were enormous differences in what particular shops would carry. All newsagents carried the mainstream UK children’s comics but beyond that there were wide variations in what was stocked. On the one hand there were respectable newsagents that wouldn’t stock anything, whether homegrown or imported, which might be classed as ‘trash’. When original US comics appeared in the 60s after the import ban was lifted some shops only sold Dell or Archie or Gold Key, but not DC or Marvel, and many didn’t carry any imported comics at all. At the other extreme there were newsagents which carried the full range of the material imported and published by L Miller, Thorpe and Porter and their even less respectable competitors. Not just comics but imported romance, western and sci-fi story magazines, and through to men’s ‘sweat’ magazines with cover illustrations of nazi’s or communists torturing semi-naked women and remaindered US nudist magazines, all alongside every kind of homegrown ‘adult’ material.

The attempt by some shops to keep trash at bay wasn’t entirely successful of course. It was one of the respectable newsagents that sold me my first scary comic – Thorpe and Porter’s 1961 UK edition of Classics Illustrated ‘The Story of Ghosts’. (The cover of this so creeped me out that I had to hide the comic where I couldn’t see it). And a few years later the first EC comics I ever saw were in the Ballantine Tales From The Crypt paperback which, of all places, I found in the remaindered paperback section in Woolworths.

L Miller’s prosecution actually had a big impact on me at the time. In 1965 I’d bought my first copy of Warren’s Famous Monsters of Filmland and the wardrobe doors to monsterkid Narnia magically swung open. I became obsessed with horror films, but since I was still too young to sneak in to see them, initially I had to content myself with the magazines about them. This developed my taste for horror and scary stuff generally, and I’d pick up horror comics as I came across them, but my dedication to the horror film magazines, particularly the Warren’s and Castle of Frankenstein, remained dominant. The erratic nature of non-mainstream distribution soon became apparent. Even those newsagents which carried a broad range of magazines wouldn’t carry every issue of any given imported title. The same applied to imported comics of course. Unlike UK magazines or comics you couldn’t place standing orders for imported titles because the shops themselves had little idea what might turn up. Smaller shops just had a spinner rack or two which they expected the wholesaler to keep stocked – these generally only carried the worst imitations of the Warren magazines and the cheapest remaindered comics but once in a while you might get lucky. Obtaining every issue of something meant cycling round a whole circuit of shops. And then suddenly in 1970 they vanished. You couldn’t find new horror film magazines anywhere in North East London. I figured there had been some kind of official crackdown. At about the same time the UK experienced one of its periodic moral panics about sex and violence in films. (Oddly enough Mike Reeves’ ‘Witchfinder General’, which Arnold Miller line produced, was one of the films that had stirred this up). In response, the minimum age for entry to X certificate horror films was raised from 16 – which I’d just reached – to 18. Radicalized by all of this monstrous injustice I began reading the underground press and discovered underground comix. . . .

Only years later, after reading Martin Barkers book, did I realise that the horror film magazines had ceased being distributed at exactly the same time as the Warren and Eerie horror comic magazines – following the raid and prosecution of L Miller and Co. (There was a bit of crossover between the two kinds of magazines – Warren had tested the waters for Creepy and Eerie by publishing comic stories in its horror film titles, and some of it’s competitors followed suit). I’m not sure that L Miller actually distributed the Warren Magazines – I think that may have been Thorpe and Porter – but neither company would have forgotten the climate of the debate when the 1955 act had been passed, and the prosecution evidently had the ‘chilling effect’ desired.

The Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955 is indeed still in force, but hasn’t been cited in a significant case since 1980, and even then only in passing and not as part of the main prosecution.

For a look at some of the ways that Alan Moore’s early work seems to have been influenced by “The Mad Reader”, see my essay at http://loopyjoe.livejournal.com/638.html

The newspaper article mentions Sir Alan Herbert (MP 1935–50) tangentially. From his courtroom fictions (Misleading Cases, also collected as Uncommon Law) I wouldn’t have expected him to come within a bargepole of supporting any kind of censorship.

Comments are closed.