Cartoonist: Lonnie Garcia

Publisher: Silver Sprocket / $15.99

July 2024

The putty in Putty Pygmalion is technically expired when Derryl the radish gets his hands on it, but nobody’s supposed to do any of the stuff he has planned. It isn’t Derryl’s devotion that brings the sculpted Peter the dog to life; Lonnie Garcia has flipped the script on inspiration and adaptation. Derryl purchases grace online. The factory-sealed lot he acquired off the internet contains both the clay kits and liquid components that can, when combined, create life. Derryl the radish (illegally) combines all the kits to make what he believes to be the perfect companion. For him. But Peter the dog is his own person. In Derryl’s house, that’s a problem.

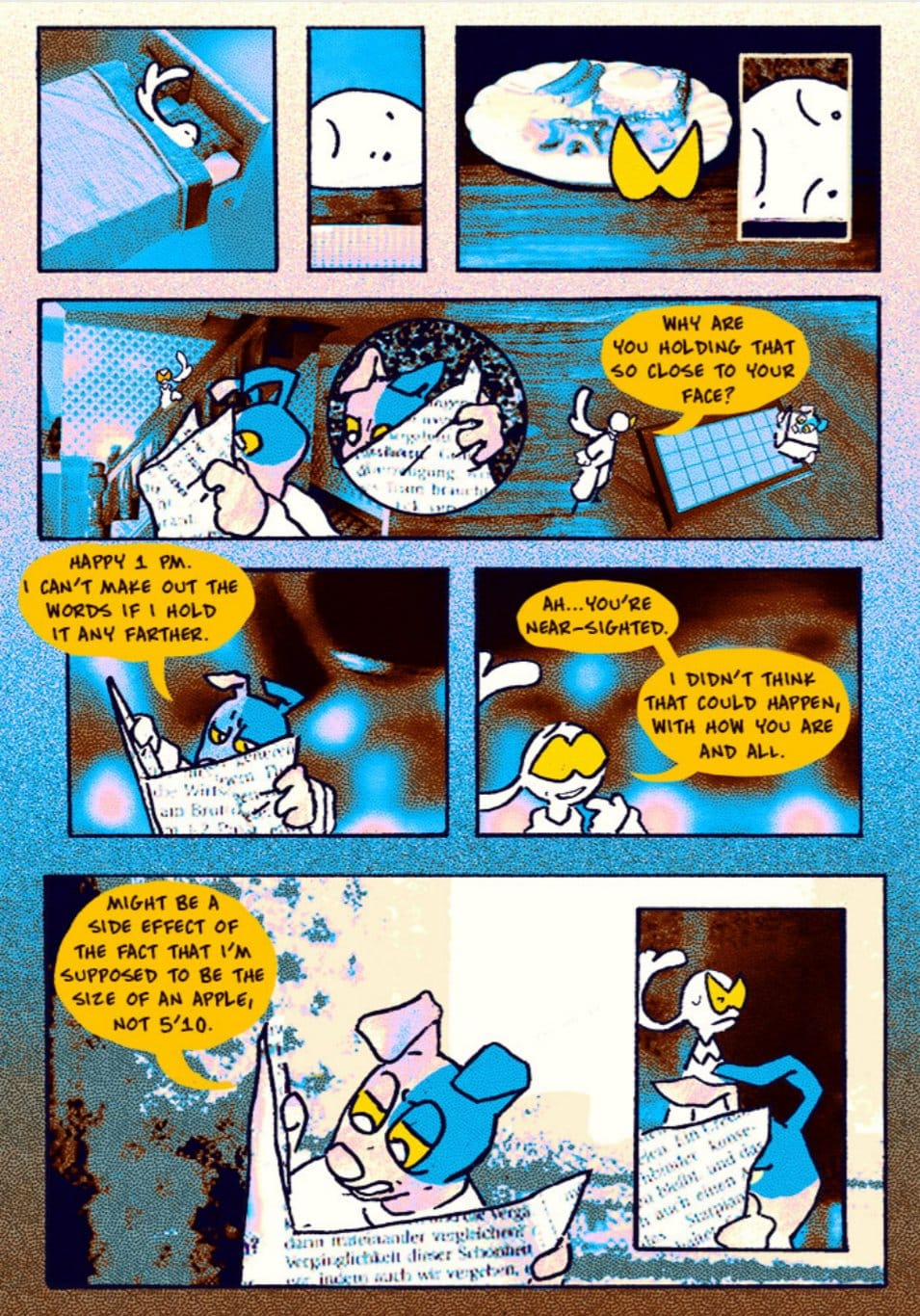

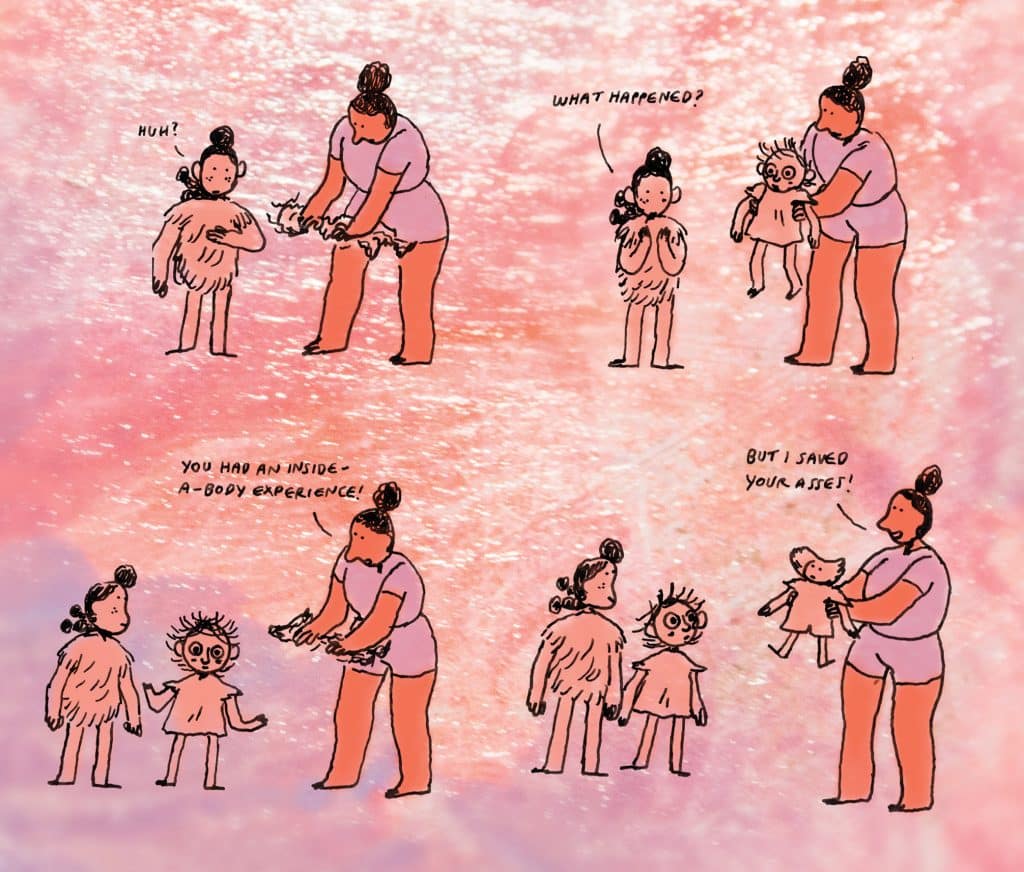

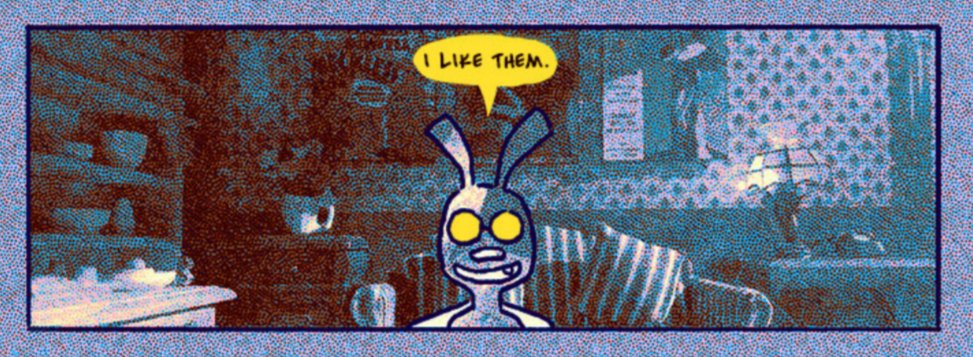

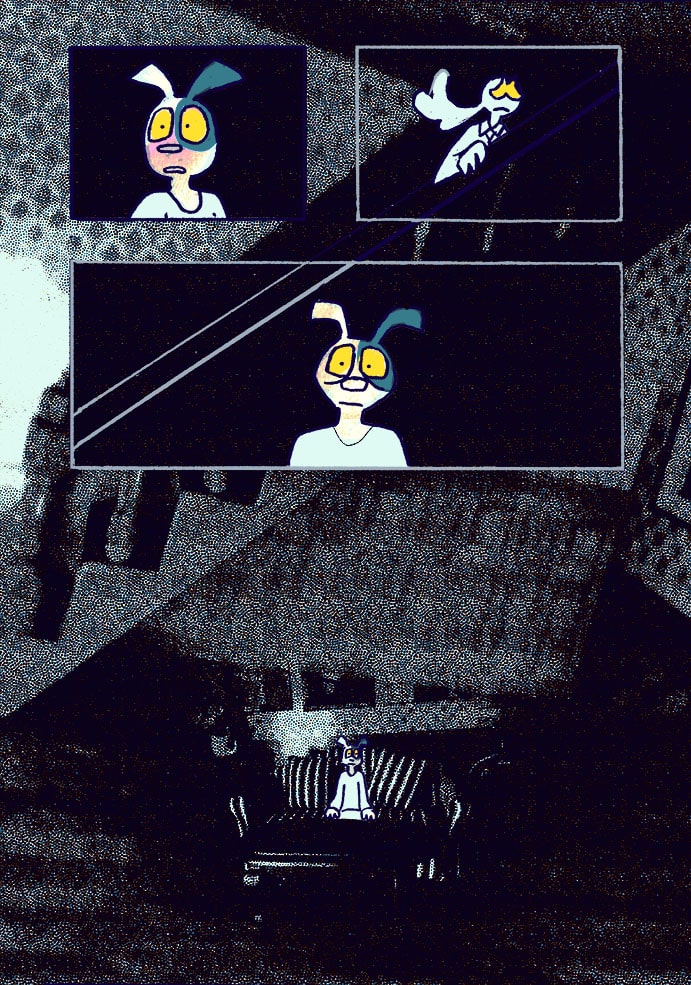

Derryl’s house is not what we’re used to seeing in comics. It’s real. Garcia’s approach is part illustration, the characters, sound effects, and emanata stuff like motion lines, on top of mixed-media: photographs of the rooms the characters occupy, or digital washes of color and woozy background manipulations. The heavily stylized digital artwork and wildly chaotic hand-drawn characters come together like a Popeye animation cell on a 30s setback tabletop shot and it is wonderful and strange. Garcia shoots photographs of a real location, then combines photos with drawings into panels, and then panels into digital layouts. People and what they say on top, flat, and imagery beneath that falls away into three dimensions.

But Peter and Derryl also fall away, into darkness. Putty Pygmalion is a Sam Shepard affair. Two men in a terse room, closed doors, ripping each other apart with words.

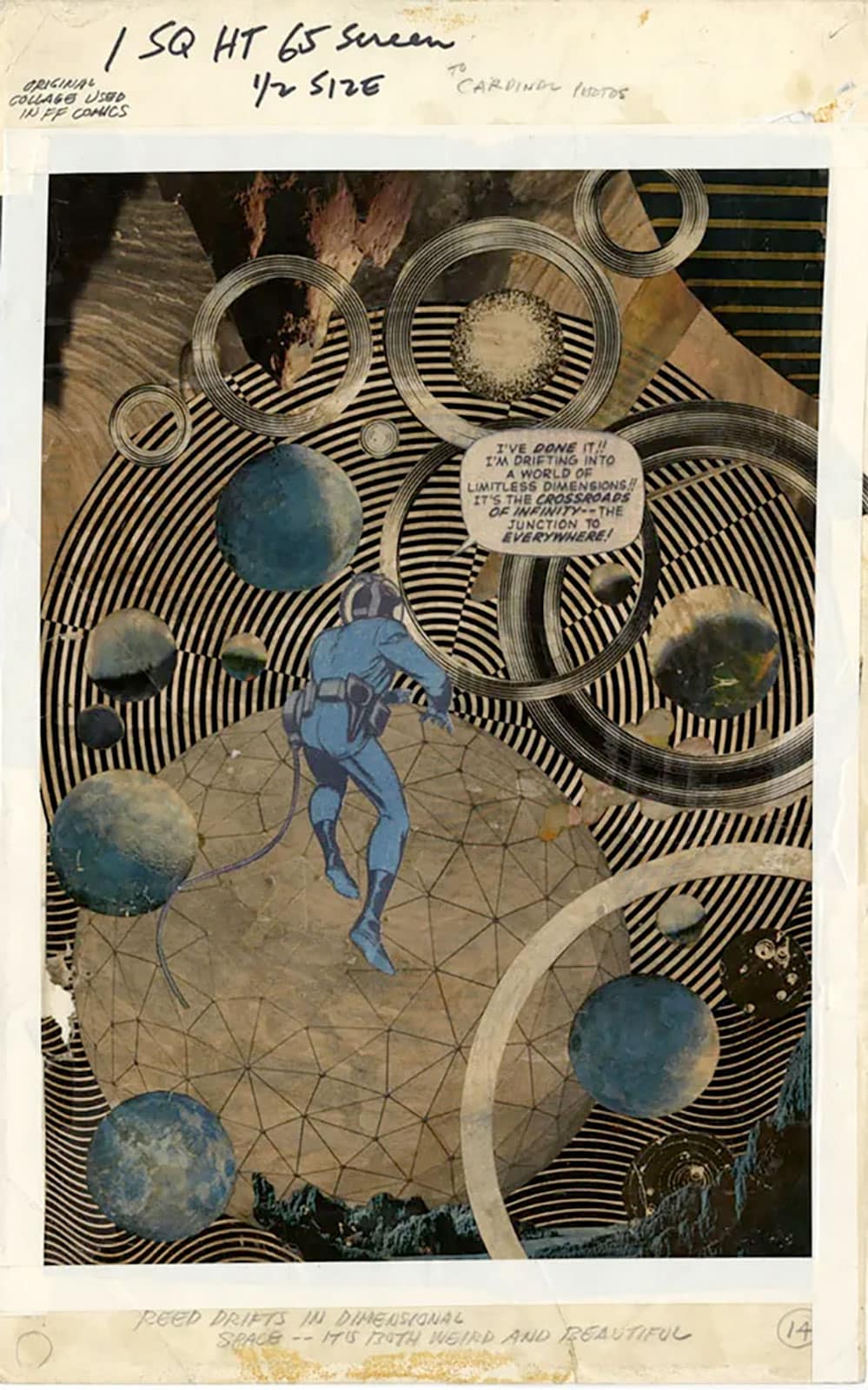

By elevating the characters up to this layer of the comics stratosphere, Garcia’s work brings to mind Disa Wallander, which is not something you can say about a lot of cartoonists. Wallander’s Becoming Horses also lifts the characters up to the same layer as the speech, and forgoes hand-drawn scenes in each panel for abstract imagery used in collage, and photography textures. Often there are no panels at all. There’s a sense in both Wallander and Garcia’s work that the characters are traveling through another world (because aesthetically, they are). Like Jack Kirby’s collage comics, the late sixties Fantastic Four issues.

And so Putty Pygmalion presents another infrequent opportunity, to consider the stratospheric categorization in comics. Speech and what Mort Walker called “emanata” (like the stars that float around a bopped noggin) exist in a contradictory, conceptual space. Peter hears exactly what Derryl is saying, but he can’t see the words we read. The idea exists, but the lightbulb doesn’t- not for the character who experiences it, only for the reader observing. Arguably it’s a defining element of comics, an essential difference between them and other pairings of words and pictures. I like the idea of the explorers being transported up into the level of raw comics while the world they’re investigating breaks the traditional concept of what comics look like, where a comic happens, what a comic is.

If Wallander’s Becoming Horses was a pilgrimage to an enlightened plane, Garcia’s Putty Pygmalion is ego destruction trapped inside the basement of a haunted house. The use of a dollhouse instead of real locations (and character tension turned up to eleven) makes me think of Todd Haynes. Maybe it’s also the fuzzy distortion of the images reminding me of cashed-out VHS, the medium of Superstar. The Max Fleischer impossibility of each panel carries over into how the layouts are conceptualized, reminding me of the magnificent computer versus notebook world of Michael Furler’s Bark Bark Girl. Another comic from the future. But! Pygmalion is of another era. There’s a FW Murnau-level control of mise-en-scene, and a familiar but overwhelmingly fabricated visual aesthetic from using a toy room with toy furniture as the (paper theater) stage. Darkened and distorted, home is made an anxious backdrop for a one-man play Peter must attend every night. Enter the doodled narcissist who is your roommate, your dad, and the reason that you’re always in danger. It’s meant to be unnerving and it succeeds.

It’s visually constructed to play with the idea of what comics can be, to test their rules, to have them be multiple things at once. The story also. It is an adaptation, though the Ovid original (?) perhaps frames the change in the sculptor to be more important than the change in the statue. The comic is concerned with the sculpture’s side. Derryl’s meddling in the basement is projection, wanting the idea of something more than the work it takes to get the thing itself. Metamorphoses had the artist admit what he wanted and get it. Garcia starts with the statue coming to life, the reward purchased in advance. Peter being forced into a situation where he is expected to act in a way that doesn’t suit him, and is potentially in real danger if he doesn’t follow house rules. He’s the one who does the work so that Derryl can have an epiphany. To free himself would be to free them both. Can Peter do it?

Peter is an impossible creature, Derryl is flawed in everyday ways that correspond with several different members of society, and their relationship reflects their ambiguity as characters. Each of them are the many kinds of people who live with each other. What matters is their behavior towards each other. You can see how, sometimes Derryl feels like one (oppressive) authority figure, sometimes another, sometimes neither and a genuine friend; you can see how cycles of abuse are perpetuated by different people who act the same way. Many are powerless, for many reasons, and they all deserve to be recognized. Free from the absolute, concrete statements about a specific type of person, Pygmalion is a lightning rod that resonates with the reader’s experience.

The undefined relationship between radish and dog allows the scene to dictate the mood instead of the actors. Yet Garcia’s ability to articulate how the characters feel (and why) causes all the artifice to eventually melt away, too, and then the story clobbers you. It gets just as hot as the atmosphere of anxiety that’s ignited by the artwork (Resident Evil Game Boy Advance), the story is just a slower burn. Drawn in by originality, beguiled by style, so enchantment snuck up on me.

Putty Pygmalion is available from Silver Sprocket or wherever finer comics and books are sold.