The cartoonist and designer known as Seth has been making comics for more than three decades. His first book It’s A Good Life If You Don’t Weaken was a critically-acclaimed award-winner and his 2009 book George Sprott was originally serialized in The New York Times Magazine. Palookaville began in the 1990s as a comic book where he serialized a number of stories, and it has been reborn as an occasional series of hardcover volumes collecting various projects. Clyde Fans was originally intended as Seth’s second book. He began the project in 1998 but abandoned it for other projects in the intervening years, always intending to return and finish the tale.

The title is an actual fan company based in Ontario; the book tells the story of two brothers who inherit the company from their father, and Seth claimed that the entire story came to him when he saw the defunct company name on a building. Seth isn’t interested in drama, though; instead, he wanted to tell a slowly-paced, meditative tale about the lives of these men in a changing world. These concerns about a world that is transformed by technology, our passion for and obsession with physical objects and the things we love and leave behind, are perhaps more relevant today than when he began the book.

Seth is also a designer known for his work on books like The Collected Peanuts and albums like Aimee Mann’s Lost in Space, in addition to his illustrated covers for the The New Yorker and his drawings for Lemony Snicket’s book series All the Wrong Questions.

I’ve interviewed Seth before over the years, and was a reader long before I ever spoke with him. I was thrilled to hold the complete Clyde Fans in my hands, and talk with him about this long creative journey for The Beat.

THE BEAT: You’re a designer and so you knew what the book would look like before you had a copy in your hands, but what is the experience of holding the physical copy? Is it this moment of triumph where you can say, it’s finished? Or does that happen earlier in the process?

Seth: In the “old days” before computers, you never really knew for sure what the printed version of anything would look like. A lot of guessing was done putting the books together and when the final printed copy showed up it was either a triumph or a terrible disappointment. That said, today you go over the finished book again and again on the screen and then again later in proofs and then finally the printed book arrives. It’s not quite the surprise it once was. For me, the final moment of Clyde Fans was probably finishing up all the actual drawings that went into the book design. When those went out the door in a FedEx package (to Drawn & Quarterly, to be assembled digitally) that is when I felt like Clyde Fans was finally done and gone. That was a satisfying moment. Not so much a moment of triumph as a moment of resignation. More like, “this thing is finally done!”

THE BEAT: How do you describe Clyde Fans to people?

Seth: I try not to! After so many years of working on the book I have often tended to avoid talking about it at all. Mostly this was due to the fact that I was embarrassed that it took so long to finish and embarrassed that anyone actually following along and reading it in serialization was surely utterly confused (because of the great lags of time between chapters). If pressed, I suppose I describe the book as a story not so much about electric fans as the story of two salesman who failed to “close” but in very different ways.

THE BEAT: You’ve said that the story hasn’t really changed since you first thought of it. Has how you thought of the characters or the story changed over time?

Seth: Surprisingly, no. I had a vision of the book right at the start that has maintained remarkably well—strangely consistent with the original plans. I certainly didn’t write out a full script back then—only copious notes about where the story was going—but I knew everything that would happen in the book and I plodded along, year after year, making that come to life. However, in comics–vs. prose–you don’t write and draw separately. They are both part of the same process. So, much of the “writing” was really done when I was drawing it. The plot remained the same. The conception of the characters remained the same – but how this was played out on the page – that evolved. The way I told the story, page by page, that changed. Not the details of the story.

THE BEAT: Your book Wimbledon Green looked and felt like your books but in other ways very unlike your work. Do you think making that and other similar books and their crazy energy affected the latter chapters of Clyde Fans? After making those fast paced books, it felt like you almost gave yourself the freedom to slow down and be more deliberate in the later chapters of Clyde Fans.

Seth: Making Wimbledon Green was an important point in my development as a storyteller. Before that I had been approaching comics in a very specific way—trying to make “serious” works in the comics form and trying to tell the stories in a very straight forward “naturalistic” approach. Wimbledon Green loosened me up a lot. The non linear nature of that book, the slap dash approach, the lack of “serious” intent—all this freed me up quite a bit. Wimbledon Green allowed me to make George Sprott. Without doing Wimbledon first, I would not have known how to approach that story. I don’t think Wimbledon Green specifically informs the later chapters of Clyde but undoubtedly, it was part of an evolving process that allowed me to draw those chapters with more sophistication and more confidence.

THE BEAT: If it wasn’t working on Wimbledon Green and other books, is there anything you can point to which changed how you told the later chapters, which are more slower paced?

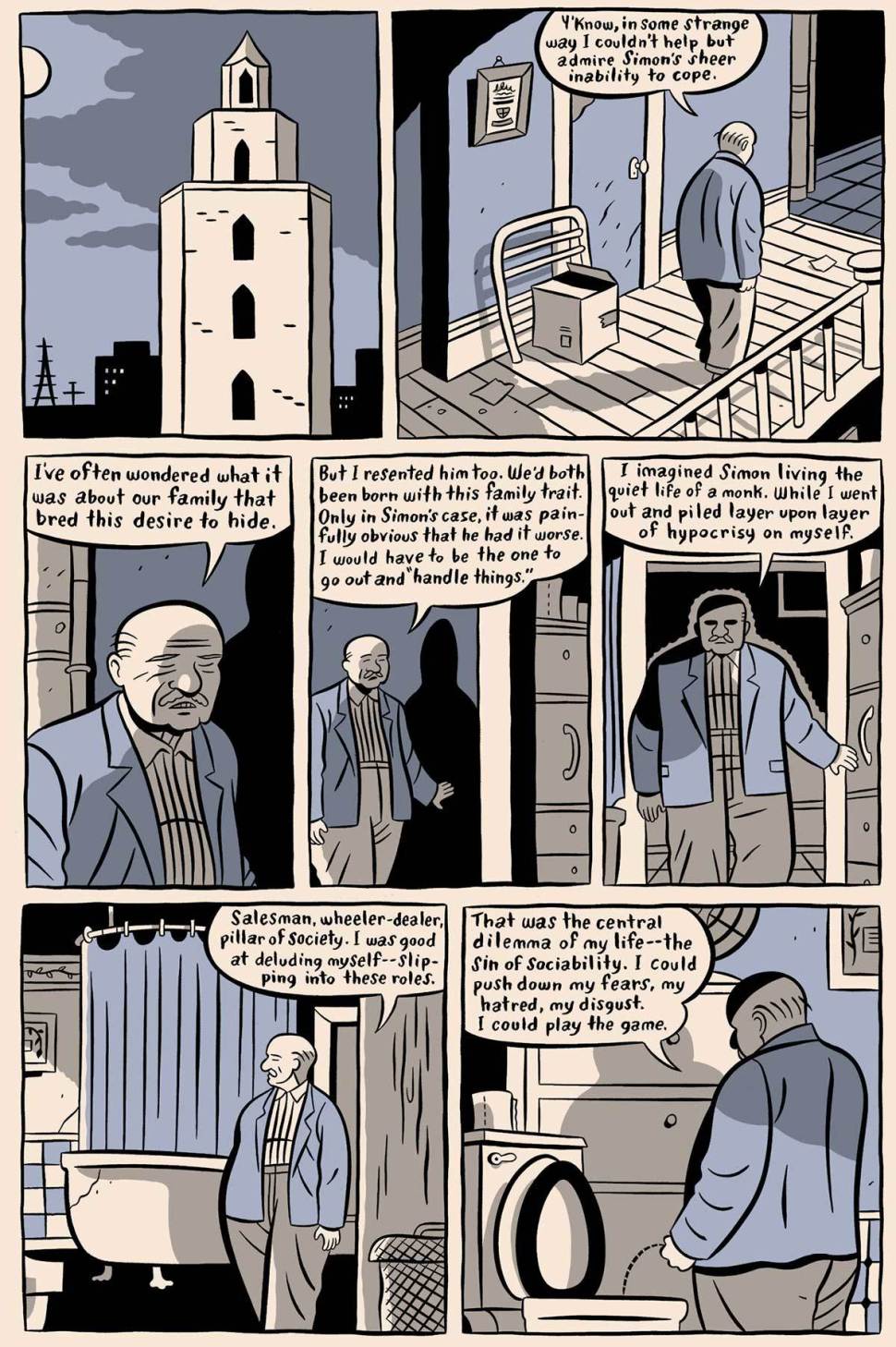

Seth: You are right. Wimbledon Green was the turning point in my thinking about storytelling. Before that book I was generally working in that “naturalistic” approach. Wimbledon loosened me up – allowing me to tell a single story with a variety of storytelling styles. George Sprott cemented these changes in my thinking. But what really changed my approach in the long run was the sketchbook memoir I’m working on, Nothing Lasts. After about 100 pages of this piece I started to notice that my regular drawing style was morphing together with my “easy-does-it” sketchbook style. Becoming flatter and more oriented toward total page design. That multi-panel, somewhat flat and design-y approach really is evident when you look at the last chapter of Clyde.

THE BEAT: You said that the way you told the story changed between the early parts and the later parts. How would you describe that shift?

Seth: Mostly it is the manner is which time is parceled out in the panels. Things slow down. They become more measured. Less information is conveyed in each panel. If you look at Abe’s dialogue in chapter one you will see two or three sentences per panel. By the end of the book I can hardly get a full sentence into a panel.

Also, the number of panels per page increases as I become more interested in how you break up actions. In other words there are less significant “jumps” between the panels. Smaller movement between panels (when the action is sequential) and pages that are more designed as whole images than I would do in the earlier chapters. This is all rather technical stuff that I wouldn’t expect the reader to notice but I would expect that these later pages give a different “feel” than the earlier ones. The earlier pages are more in a tone I call “naturalistic” storytelling – where you follow the character around watching them do things – the later pages are have more variety in approach.

THE BEAT: Reading it in one sitting like this, there is a way in which Clyde Fans is more about the elements of their lives and the physical reality of their lives rather than drama or events. This isn’t some big tragedy or even that dramatic or uncommon a story. I think it’s easy to read that as nostalgic, but I am curious where that interest comes from for you? Both as a person and as an artist.

Seth: Increasingly, as I get older, I’ve realized I’m not much interested in conflict (or drama) as the point of a story. What appeals to me is the everyday reality of our lives and how we relate to that strange experience of inside and outside. What I mean by that is the weird relationship between the inside experience (the mind, or the body) and the outside experience (the world of “reality” outside of us). So, I suppose, that tends to bring a story down to characters “talking” about thoughts, memories, sensations etc. I suppose my idea of a story is more of a rumination than a sequence of events.

I’ve also very interested in objects and how we relate to them—in some manner I’m almost tempted to just describe places and things as stories in themselves. I suppose this all sounds terribly self indulgent and not very welcoming to the reader but, all this set aside, I’m awfully concerned with maintaining a clear and inviting reading experience as well. I’m certainly not aiming to bore anyone—I trust the reader will follow along with me. I try to make the storytelling beautiful.

THE BEAT: I keep thinking about the relationship between this book and an exhibition because there is a certain slowly paced rendering of surfaces and details and exploration of those elements, leading the reader. Was that part of what you were going for in some of the scenes?

Seth: Your use of the word “exhibition” is a good one. I am trying to place things/scenes in front of the reader and simply let them view them—take them in. There is something so delicious about the process of describing things. Often when I am reading a novel the thing I most enjoy is the long slow sections where the author describes the setting. Sure, I’m interested in seeing the plot moving along too but I’m also happy to slow down and just wallow in the pure description. Lately I have been wondering if you can make an interesting story entirely out of description. I think so. I’m thinking my next book may very well try to do just that—or at least a lot of that.

There is a great under-explored power in everyday objects or settings. I certainly feel it in my life—so many things have a kind of totemic power about them. I think the monk Thomas Merton said (and I’m paraphrasing this), “that to see objects as meaningless we must first see how much meaning they have”.

THE BEAT: I’m guessing that you’re not a Marie Kondo fan. Or maybe I’m wrong, because you do love and obsess over objects.

Seth: Yes and no. Certainly I’m no minimalist! My home is full of objects. But not disorderly. Carefully chosen objects and carefully displayed. I am no hoarder. I like order in my life and although I own way too much stuff it is all carefully displayed or carefully hidden away out of sight. As you can probably tell from my artwork, I dislike clutter. All that said, I cannot imagine living a life without all these possessions. They aren’t just things to me—they are extensions of my identity. Invested with meaning and some kind of mystic power. Maybe that’s all pretentious and sentimental nonsense but I feel it nonetheless. The only objects threatening to overwhelm me are books. There are far too many books here and they are starting to form piles on their own.

THE BEAT: I also keep thinking about how the themes of the story – technology and loneliness and the passage of time and our attachments – are, if anything, more relevant today than when you started.

Seth: When I started the book the metaphor of being plowed under by progress was certainly more generic than when I finished. In fact, a lot of what I was thinking about back then was how the comic book medium was coming to an end (late ’90s—comic shops closing, publishers going out of business, etc.). Like the brothers in the book I hadn’t expected that and I was kind of flabbergasted that it looked like I would soon be even further marginalized as an artist. The big surprise was that the public acceptance of the graphic novel was just around the corner and things actually started really looking up around the year 2000. However, you are correct, strangely Clyde Fans has ended up being more about current events than I had planned. You never really know what a book is about until you finish writing it (if even then).

THE BEAT: As you mentioned, you’re not especially interested in plot as a storyteller. Are not interested much as a reader or viewer? I’m curious about other cartoonists or filmmakers who were an influence particularly in terms of pacing and your approach.

Seth: It is true that I am particularly attracted to slower works in every medium. More so even as I get older. A hugely influential work for me is The Last Year at Marienbad by Alain Resnais. The elliptical narrative of this film continues to fascinate me more every time I watch it. The same can said for To The Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf. In recent years this book, which I have read a dozen times at least, has become my favourite book – the middle chapter, “Time Passes,” is practically a guide to what I think is an ideal story.

Speaking of writers, in the last few years I read the entire body of work by British author Anita Brookner (another new favourite). Her slow pace interior novels have great appeal to me. I could go on and list many such favourites. Another work that has long influenced me is Indeterminacy by John Cage. These 90 stories told in 90 minutes have been important to my idea of storytelling since I was in my early 30s. I’ve never tired of what he did there. Picking favourites and making lists is something I deeply enjoy. Watching your tastes change and refine is an interesting aspect of charting who you think you are at the moment (or maybe who you wish to be).

THE BEAT: Have you started thinking about your next big project, though hopefully not a 20-year project? Or are you thinking, I’d like to make a self-contained short comic?

Seth: I have. It’s funny, while working on Clyde I certainly had many years to plan my next book and I had about five possible stories that might have been the next one. Typically though, once Clyde was done, a totally new story suddenly appeared, fully formed, in my mind and so that’s going to be the next book. Will any of those other stories ever be done? Who knows. This new one will be shorter. And, dear God, I hope it will not take 20 years. I figure it will take about three volumes of Palookaville to serialize it (yes, I am going to serialize it). Three solid, self-contained sections that should be enjoyable individually to a reader. Fingers crossed. I hope to do these Palookaville volumes as long as possible. I really enjoy doing them. Especially because they allow me to pursue and show off various things I’m working on in my sketchbooks or the studio.

THE BEAT: You mentioned you’re going to keep making Palookaville volumes. And you have finished Clyde Fans but also had other projects in the recent volumes. What do you like about serialization? What does it offer you?

Seth: Probably serialization is a compromise at best. Ideally, I suppose, it’s best to present a finished book to the reader. However for me, as the author, it allows me to get a chunk of the story done in a “reasonable” amount of time. A whole book at once is a daunting task when you have to draw all those pages. I’m the kind of artist that works on a wide variety of little projects at once rather than one overriding project start to finish.

So, getting some of it out the door in an issue of Palookaville is very satisfying to me and encourages me to keep working. I also love making the volumes of Palookaville because they allow me to showcase different things I am doing. There are a lot of projects here in the studio that almost no one has ever seen and including some of it in the books is helpful to me. Even something as public as my wife’s barber shop, for example, isn’t seen by almost anyone who knows my work. However, once I had included it in a volume of Palookaville then it went out into the world and changed people’s perceptions of what I do. That is valuable to me. It means people get a wider view of my work and hopefully interesting opportunities come along because of that changed perception. In some ways, I like to keep work private but in other ways it is simply that I don’t have a venue to always show things in a timely manner.

THE BEAT: Clyde Fans was an actual company. Have you seen any of the fans they made? I’m assuming they were small regional company but do you get people saying, I know them, or I still have one?

Seth: Yes, Clyde Fans certainly was a real company but, from what I know, it was a rather small concern. I do have a beautiful large stand up fan from the Clyde Fans company. They are not common items. I’ve never seen another one, though I have met a couple of folks who own a Clyde fan. Surprisingly I don’t have a particular affection for electric fans. I like them but not more than any other old objects. It was a pretty random decision, all those years ago, when I picked electric fans as the subject of my book. If the real storefront that inspired this book had been a printer or a haberdashery the book might have been called CLYDE PRINTING or CLYDE HATS. Thinking back I see how much serendipity was involved in the whole thing!

Clyde Fans is currently available wherever books are sold, as well as on the Drawn & Quarterly website.

Uhm… minor correction: Seth NEVER abandoned CLYDE FANS. The bulk of any given issue of PALOOKAVILLE was given over to it. The totality of the floppies, and then the typically largest segment of the hardcover versions.

Comments are closed.