Last week, I reviewed Aron Nels Steinke‘s latest graphic novel, SPEECHLESS (Graphix). It was a great conversation, and it’s so nice to chat with someone who has established himself as a creator of insightful and visually captivating narratives that genuinely reflect the everyday realities of childhood. His storytelling intertwines humor, emotion, and a perceptive understanding of adolescent drama. His oeuvre highlights the seemingly minor yet impactful experiences of youth that shape us—such as forming friendships, facing personal challenges, and finding a unique voice. His merging of compelling stories with vibrant illustrations vividly portrays school life’s joys, challenges, and idiosyncrasies. Whether illustrating the lively atmosphere of a classroom or the worries of youth, Steinke’s books are certainly celebrations of small achievements. The following is our conversation:

AJ FROST: Hey, Aron! It’s nice to chat with you again. It’s been a while. I wanted to start by asking how personal experiences shaped your approach to depicting selective mutism as the subject of Speechless. Relatedly, what research or consultations influenced your depiction of selective mutism beyond your personal experience, particularly in a contemporary middle school environment?

ARON NELS STEINKE: The seed for this book grew out of my own childhood anxiety and difficulty speaking. It wasn’t until I was a teacher that I discovered the term selective mutism, and I immediately identified with it. I prefer the term situational mutism, because it more accurately describes the condition. When someone with SM doesn’t speak, it’s not because they’re choosing not to, it’s because their amygdala (lizard brain) is telling their body to freeze when confronted or asked to speak in certain situations.

While I was teaching, I also got to work with a fifth grader who didn’t speak at all in school. After I inquired, I found out that he spoke at home with no difficulty, and in fact, was actually quite verbal. I don’t know if he had been diagnosed with SM, but that was when I really got to thinking about this condition. As with other conditions there is a spectrum–not everybody’s symptoms are the same or as acute–and there are also other reasons why kids may not speak, but the more and more I read about SM through books and information available online from SM clinics and therapists who treat kids with this condition, the more I wanted to make a book that incorporated this topic.

I ultimately chose to explain less about the condition in my book. Selective mutism is not rooted in trauma, but it is often associated with social anxiety. We all experience social anxiety on occasion to some degree. Mira’s condition is just more of an extreme. But, ultimately this book is about friendship. And what happens when you lose your best friend. What happens when you have to confront that former friend? How do you deal with bitter feelings and resentment? How do you make new friends? That’s autobiographical too. I still have strong feelings about friendships I’ve lost. Mistakes I’ve made, and unexplained friendship breakups. Who doesn’t experience that?

FROST: Just to follow up: what do you think attracted you to this topic as the subject for a graphic novel, especially one aimed at the middle grade demographic?

STEINKE: It’s reported that about 1 in every 140 kids has some kind of SM. They are usually misunderstood as being purposefully defiant, rude, or just shy. They are more vulnerable to being victims of bullying or treated unfairly by their teachers, and most people have never heard of it, but they do know someone who has it. It’s kind of a silent disability. No pun intended. Because I experienced SM as a kid, and once I had the words to describe that situation, I needed to share my learning with other people. I want to acknowledge that pathologizing giving labels to or trying to fit everything into a box can be problematic, but labels can also be a tool for understanding oneself and for getting help. It’s a complex subject, and I think the panic and anxiety Mira feels is relatable to most middle schoolers. As a tween and young teen, your body is changing; hormones are upending everything you thought you knew. Middle school was a VERY difficult time for me. So I made this book to give kids hope. To acknowledge the difficulty but give them hope that they can do it and that it does get better.

FROST: Could you elaborate on the artistic techniques you utilized to convey Mira’s emotions, particularly during instances when she faces challenges in verbal communication? What compositional techniques guided you to explain her inner turmoil?

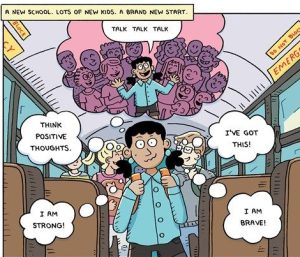

STEINKE: Mira doesn’t speak in school, so in order to understand what she’s thinking I let the reader in by giving Mira thought balloons. In an early draft I discovered that if I gave away too many of her thoughts, the reader might not actually feel that Mira can’t speak in school. But I didn’t want to remove all the thought balloons, because it would then be harder to really know how she was feeling and what she was thinking. I needed the reader on her side right away. So it was a balancing act to try and share both her inner thoughts and give the reader the accurate experience of not hearing her speak.

FROST: Could you explain your decision to use stop-motion animation as Mira’s creative outlet? What aspects of this medium do you think make it appropriate for her character? Is stop motion animation something that you’ve been personally involved with on a creative level?

STEINKE: Again, everything I write is autobiographical to some degree. Mira is obsessed with making stop-motion films because I had started making my own hand-drawn animated films when I was a teenager. More recently, I’ve started fabricating my own stop-motion puppets for fun. I live in Portland, Oregon, which is the unofficial capital of stop-motion filmmaking, and right before the pandemic my son and I were given a tour of the Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio film sets and production offices. It was incredibly inspiring to see artists bringing puppets and sets to life. The claymation pioneer Will Vinton was from Portland, and his studio eventually morphed and evolved into Laika Studios (Coraline, Kubo and the Two Strings). The stop-motion shows In the Know and The Tiny Chef Show are all currently being made here as well. My 12-year-old son is an extremely talented filmmaking wizard, and I was certainly thinking of him when I was developing Mira and her passion for filmmaking. I’m also a big believer in art as therapy, so to have Mira making these stop-motion films was a good way for her to process her feelings and figure things out. That’s what I do. Mira does end up seeing a real therapist, by the way, who gives her tools to help move through her anxiety. I called upon the expertise of a relative of mine who is a child therapist to proofread those scenes and give feedback.

FROST: How did your former professional experience as an elementary school teacher inform how you approached the material for Speechless?

STEINKE: I had been writing for kids before I started teaching, but I didn’t have much experience working with children. But when I started teaching young children I finally gained the perspective and context I needed and a much better understanding of how to write for them. My advice for anyone who wants to write for kids is that you need to spend time with kids. Period. If you can’t teach, go out and volunteer. Read to kids. Hang out with relatives who have kids. There really is no other way. But I quit teaching in 2020 and started the idea for Speechless about a year after. That immediacy of being in the classroom was something I had always relied on while writing Mr. Wolf’s Class. Small anecdotes would always find their way into those books, but once I didn’t have that immediate inspiration, I went back and mined more from my past experiences as a middle schooler. This is a very personal book for me. Grades 6-8 were the worst years of my life. Not because of anything external happening, but just the usual developmental stuff associated with puberty, and I just let Mira feel those same feelings.

FROST: Although Mira is the protagonist, the supporting characters are also noteworthy. Specifically, the inclusion of Alex as a nonbinary character adds depth to the narrative. Could you elaborate on the process of developing their role as both an ally and project partner for Mira?

STEINKE: The Alex character is an amalgamation of a friend I made in sixth grade and my son’s best friend in elementary school, and then fictional beyond that. I wanted Alex to be Mira’s cheerleader, even if she thinks she doesn’t deserve them. She kind of fails Alex at one point and expects Alex to leave, but they don’t. They forgive her, because they actually really care for her and deep down, they don’t relate to a lot of the other kids, even though they could easily be friends with them. Alex is nonbinary, because I have many queer, trans, and nonbinary friends, colleagues, and family in my life. We only know Alex identifies as nonbinary because they/them pronouns are used a few times. It’s not addressed beyond that. It’s not an issue. It’s just reality. It shouldn’t be a big deal. That said, writing for kids is a responsibility that I take very seriously, and if I’m not standing up for the most vulnerable people among us, then I should quit making books altogether. I’m not perfect, but I am consciously trying to make work that has a positive impact on society. But I’ll never lecture or write a polemic. My goal is to make art that tells the truth.

FROST: Could you share how Mira’s multiethnic heritage relates to her experience of selective mutism? For instance, do you believe that her background (Jewish – subtle; brown skin – apparent) influences the way she navigates her social environment and the challenges she faces with verbal communication? Additionally, why did you draw on specific cultural references to incorporate into her character?

STEINKE: I wasn’t setting out to write a book about gender, race, or religion. We only know Mira is Jewish because she mentions Hanukkah once and there is one scene where she and her family are eating dinner with challah while her dad is wearing a kippah. One scene references matzo ball soup. So, it’s subtle, but it’s a reflection of my life. I converted to Judaism a couple of years ago, after about ten years of stalling. My wife is ethnically Jewish–Ashkenazi and Sephardic (where she gets her olive skin), and I imagined Mira’s mom as Sephardic/Mizrahi and her father as Ashkenazi or maybe even a convert like me. Regarding race, it is rare that you see non-white Jewish characters represented in the media. Do you remember when that Daveed Diggs Puppy for Hanukkah video came out back in 2020? That was incredible–to see a mixed-race Jewish kid in a high-profile Disney video. Such a fun song! Now I’ve got it stuck in my head.

FROST: In creating a narrative that addresses anxiety and social challenges for a middle grade readership, how did you strike a balance between tackling serious themes and incorporating humor? And how do you achieve this balance without coming off as overly didactic?

STEINKE: All my favorite television shows and movie dramas incorporate humor to balance out the darkness. So that’s what I aspire to. Nobody wants to be lectured, children especially, which is why I focused more on the narrative and the friendship issues, rather than specifics about an SM diagnosis. Also, the way I draw adds a form of humor and lightness all on its own. For instance, there’s a scene at the start of the book where Mira comes home after her first day of sixth grade. She’s had a terrible day and SLAMS the door shut as her dad is trying to check in with her. Then, in the next panel, she has this wild facial expression with eyes bulging and fists clenched as her dad looks taken aback. The slamming of the door makes me laugh. Her facial expression makes me laugh. It’s not laugh-out-loud funny, but it’s a levity that allows you to get through the tough stuff and makes you invested to go on this journey with her. There’s also this love/hate sibling relationship between Mira and her younger sister Madi that is relatable to anyone who has grown up with a sibling.

FROST: Are you working on anything else now? Anything you can publicly share?

STEINKE: I’m working on Mr. Wolf’s Class Book Six: The New Student (Summer 2026 from Graphix)! I’m having so much fun with this book. It’s much more humorous and is much lighter than the issues I was dealing with in Speechless, so it feels like a good reset before I figure out what’s next after that.

Speechless is now available at your favorite bookseller. You can follow Aron on social media, including Instagram and Bluesky. Updates can also be found on his website.