Here’s the third part of my interview with the late Steve Moore, with more to follow. The first and second parts are already online, along with some explanation of how the interview came about.

PÓM: You did eventually leave to work as a freelance writer, though, didn’t you? What brought that about?

SM: Mainly my short attention span, I think. I tend to have enthusiasms for things, which might last months or years, but eventually I start looking for novelty. And I think I also realised that I could end up as an editor like Bob Paynter: a company man with a well-paid job who’d be doing the same thing for year after year. And at just 23, I wasn’t really looking for long-term security.

PÓM: What did your parents think of all this, first you giving up the job at the flour mill, then giving up full-time work altogether?

SM: You can add leaving school to that list as well. I suspect they thought I was mad, but looking back they seem to have been remarkably tolerant, and they basically said ‘Well, if you’re sure that’s what you really want to do …’ Mind you, I think my dad had pretty well given up on me as, unlike my brother, I showed no interest in football or going to the pub, so I was obviously turning into an incomprehensible weirdo. I never felt particularly close to my father, and I remember feeling the need, after doing something inane during my teens, to justify it by saying ‘I’ll grow up one day …’ He told me not to hurry, which I actually find rather touching, and that’s the only advice he gave me that I actually remember. I was much closer to my mum, and she, in particular, was plainly aware that I was miserable in all three of those situations, so essentially she gave me her support (and, of course, by the time I decided to go freelance, my dad had passed away a few months earlier). It has to be remembered, too, that it was a hell of a lot easier to get a job in those days than it is now, and I suspect they thought that if things didn’t work out, I’d be able to find something else to do.

->PÓM: You obviously had faith in your ability to write, to have decided to go freelance?

SM: Looking back after 40 years or so, I can’t really remember! I suppose I must have, but I suspect I thought ‘Yes, I can do this’ rather than ‘I’m really good at this.’ Self-confidence has never really been my strongest point (I dread reviews!) and, as I said earlier, I rather stumbled through things. People would ask me to do something – I had no idea whether I could, but did it anyway – and then it turned out alright in the end. But as I also said, reliability was one of my strong points, and that carried me through a lot. But would I have had the confidence to go freelance without the thought that I also had a ‘career’ at Bookends at the same time, to support me if it didn’t work? I just don’t know. That got me out of the editorial rut at IPC, and though Bookends didn’t work out, once I started working from home I knew that was where I wanted to be, not in an office job. So ever since then I’ve been doing absolutely everything I can to make sure I didn’t have to ever get a ‘proper job’ again. And confident or not, I’ve pretty well got away with it so far.<- PÓM: You mention that creators were anonymous when you started working in comics. Do you think, after all these years, that it was better or worse that they are all getting credit for their work now?

SM: Bit of a moot point, this one. On the one hand, I think that creators should get credit for their work, and obviously it’s good for their careers if they can show potential employers work with their name on. On the other hand, back in the days of anonymity, there was far less ego in the business, no quarrelling in public forums, fewer people behaving like arseholes. There’s also a disadvantage to credits, of course, which is that, particularly in British comics, editors have had a tendency to edit a writer’s work without consulting them before publication (and yes, I know I used to do this myself in the ’60s, but that was part of the culture). As a writer, of course, I find that absolutely infuriating, because what’s being presented with my name on it isn’t what I wrote … which is much less of a problem if one’s anonymous. That’s always been one of my major gripes with the comics industry: the publishing and editorial people seem to have very little respect for the creators that they depend upon. And after all, it would seem to me to be only a common courtesy to discuss the changes one wishes to make to someone’s work with them. Rarely happens, though.

PÓM: Do you remember how much you were paid for that first ‘Pow Short Story‘? And is there a particular reason that you have it styled that way, i.e. ‘Pow Short Story‘?

SM: I really can’t say for sure about the payment, as I’ve always tended to throw out my account books after the six years you need to keep them in case there’s a tax inspection (which also means, unfortunately, that I have no record of exactly what I wrote over the years). I’m guessing that it would be something like £5 a page.

SM: I found this much more noticeable when I moved to Fleetway House where, as I mentioned when talking about the staff of Valiant, most of the editorial people could have come straight out of the 1950s, rather than the late 1960s. It wasn’t quite so bad at Odhams but, obviously, at both publishers all the decisions about editorial direction were taken by older members of staff who’d worked their way up to the top. I rather think that comics publishers and editors tend to be innately conservative, and generally any new thinking tends to come from the creators, usually in spite of the publishers. Unfortunately, in mainstream comics these days, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of new thinking coming from anybody, which is why we keep getting these turgid retreads of stupid superhero stories.

PÓM: How were work conditions then? Were you treated well, paid well, given much in the way of holidays, that kind of thing?

SM: All the editorial staff were in the National Union of Journalists, so naturally we got union rates of pay, union hours, union holidays, and so on. And those were still the days when you didn’t mess with the unions, so conditions were generally pretty good. I certainly had no complaints.

PÓM: How did you go about pursuing your new career as a freelancer? Did you have any idea of what you wanted to achieve, or were you making it up as it came along?

SM: Basically, my plan was to get as much work as I possibly could, of any sort whatever, though mainly in the adventure field. Really, the only way you can ‘learn’ how to write is to do it, and to do an awful lot of it. So a lot of my career was built on reliability and versatility. I may not have been as flashy as some other people, but I always got the work in on time, and I could do just about anything in the adventure field, though the stuff I was always more interested in was SF and fantasy.

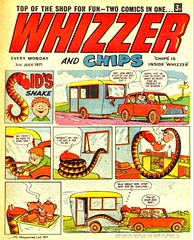

But my main employer when I first went freelance was John Barraclough, who’d been editing Buster and left IPC a couple of months before I did. He then started editing a weekly for a slightly older boy’s market called Target, published by New English Library, though John had his own office in the Charing Cross Road. I continued to work for John throughout the 1970s, and basically he was a dream to work for. He accepted everything I gave him, and never changed a word. I’d like to think that was because he had perfect trust in me, but I suspect a certain element of laziness was involved as well.

Each week, Target ran a two-page adventure strip, two one-page humour strips and a two-page text serial, the rest of it being taken up with features on sport, movies, music and so on. The first thing I wrote for it was a four-part horror-thriller called ‘The Curse of the Faceless Man’, and then went straight into a sword-and-sorcery strip called ‘Orek the Outlander’, which ran through three series of about 10 issues each. They were drawn by continental artists, probably had very little going for them and were undoubtedly derivative … I recall a fight with living skeletons that was certainly inspired by Ray Harryhausen’s work on Jason and the Argonauts. But I had a regular series, I was having fun, and I was getting paid.

At the same time, John also asked me to start writing the text serials, which usually lasted about four episodes. Naturally I had no experience whatever of writing these, but I just banged stuff out as best I could, and John took everything I gave him. And such was his relaxed attitude that he pretty well left me to suggest what I wanted to do. So I did SF, horror, adventures with mercenaries and stuntmen … all ripping yarns with titles like ‘The Horror in the Churchyard’ and ‘The Scourge of Planet X’. I had enormous fun working for Target.

Target wasn’t the only thing John was doing. It seemed the Swedes had an insatiable appetite for Tarzan, but were running out of Gold Key material to reprint, so John somehow managed to land the contract to supply them with extra, original material. So at the same time I was also writing 16-page complete Tarzan stories (and I think I did a couple of Korak, Son of Tarzan stories too). I can’t remember, but I think I wrote between 10 and 15 of these … but being published in Sweden (and in Swedish) I never saw a single one of them in print, so I’ve got no idea how they came out.

And, of course, all this stuff was being written in between serving customers at Bookends, six days a week. The energy of youth …

PÓM: Did you actually manage to make a living as a writer, right from the start?

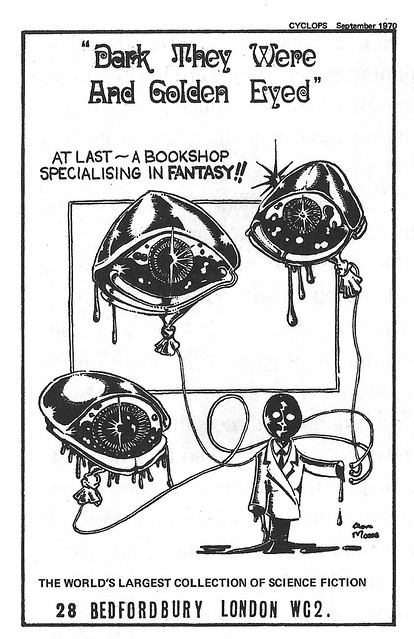

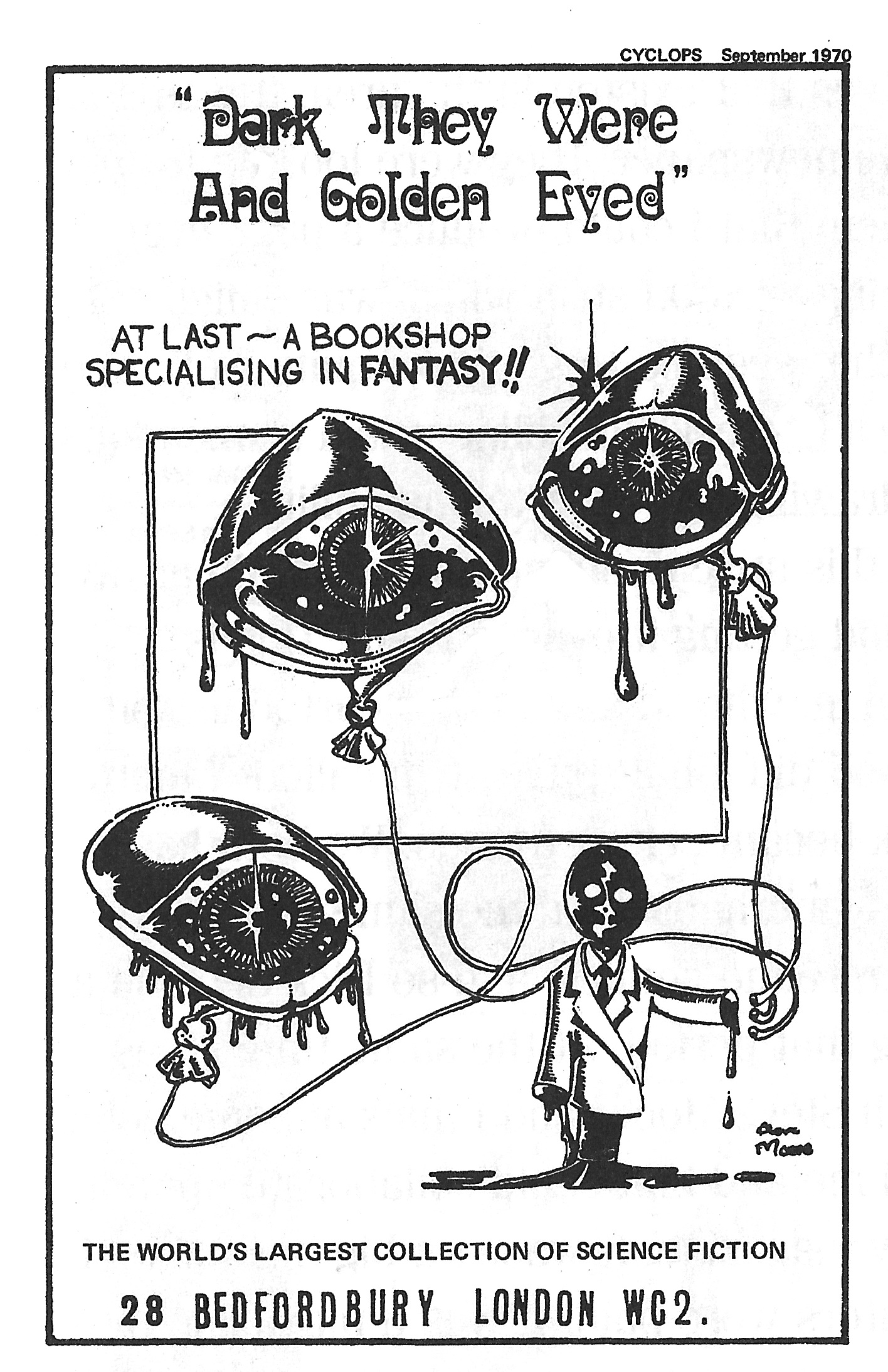

SM: Pretty much so, but you have to remember I was living at home. I had no mortgage or rent to pay, and no family to support, and that applied throughout my career. If that hadn’t been the case, I would either have had to work a hell of a lot harder, or get myself a proper job. As it was, there were times in the mid to late ’70s when work was a bit thin, and I’d work a couple of days a week at DTWAGE. But all the time I was at Bookends I supported myself entirely by writing, and never took a penny out of the shop.

PÓM: How long did the bookshop last? What was it like? Were you in it all the way to the end?

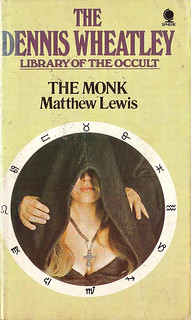

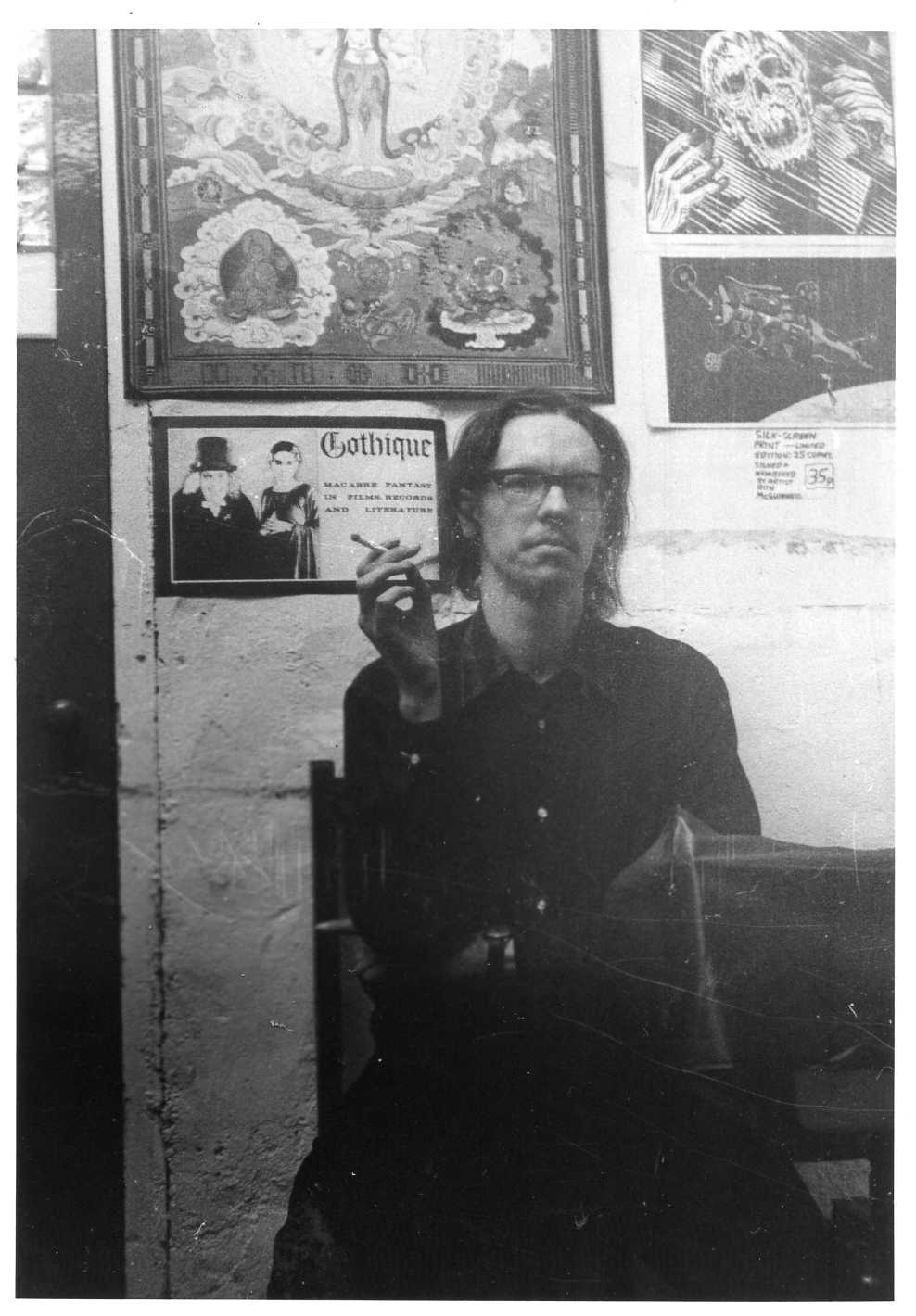

SM: Bookends closed in late 1973, so I was there getting on for 18 months; I think it had been open a year, or maybe two, before I joined it. It wasn’t a very big shop. The main sales area was on the ground floor, where we sold ‘hip’ books on drugs, the occult, modern fiction, poetry, a little SF and some underground magazines and comics. There were two rooms in the basement: in one we sold new and second hand mainstream comics, and I also wrote down there. In the other room, at least to start with, was a mail order SF and fantasy book service run by Ted Ball and Dave Gibson, who later moved out to set up the Fantasy Centre at 157 Holloway Road, where they continued trading into the 21st century. At this point, though, we were trying to persuade them to move out, because we needed their room as a stockroom, and there was a certain amount of tension involved. This made it rather embarrassing in later years when I actually wanted to go and buy stuff from the Fantasy Centre, but I just pretended not to know Ted, and I suspect he may have done the same, though by then I’d changed my hairstyle and grown a beard, so it’s possible he may not have actually recognised me.

Obviously that didn’t help the finances, and shortly afterwards the shop went bust with something like £5,000 worth of debt. Most of the remaining stock had to be sold off for a fraction of its worth. Our ‘sleeping partner’ decided to absent himself at this point and Stan Nicholls, whose sole means of support had been the shop, obviously didn’t have any money, so I ended up having to pay off the debt myself, which basically wiped out all the money I’d saved up at IPC to give me some cover for the start of my freelance career. Not the most auspicious of starts.

PÓM: What attracted you to the Chinese films?

SM: I think the most immediate cause was simply their exoticism. As I said, I’d stayed in touch with Bob Rickard, even though he was still living in Birmingham at the time, and he shared my interest in Japanese samurai movies. Then one day he told me that he’d discovered that Chinese movies were being shown at 1:00am at the Odeon in Birmingham at the weekend, mainly so Chinese restaurant staff could see them after work. So the next weekend I was up there, and saw a movie called The Sword, starring Wang Yu. This was a few months before Bruce Lee came along and started the whole contemporary kung fu boom, so the majority of Hong Kong and Taiwan movies were still ‘historical’ swordfighting stories. I put ‘historical’ in quotes, because they were actually wuxia or ‘martial hero’ movies set in a somewhat fantasised version of historical China that derives from a literary genre that goes back at least to the 15th century, and novels like The Water Margin. This is the stuff I’ve always preferred (and still do), rather than the straight ‘kung fu’ film, which fortunately was a fad that blew itself out after a few years, to be followed by a return to wuxia.

I was struck by the costumes and sets, the incredibly high pace of the action, the skilled fight-arranging and some very gorgeous leading ladies. But I was also attracted by the notions of honour, integrity and self-sacrifice that come with the ‘chivalrous hero’, and the fact that the stories were frequently tragic in a classical sense. All that I find very appealing. And apart from anything else, there was just this entire alien, fascinating culture to explore.

PÓM: You say they caused a ‘major shift’ in your life. How did this manifest itself?

SM: In several different ways. For a start, there was the simple fact that I spent a large amount of my leisure time in the early and mid-1970s hanging around in Chinese cinema-clubs in the Chinatown area around Gerrard Street in London, of which there were at least four. Of course, it was only with hindsight that I realised that at least some of these were likely to have been run by Triads, but at the time I was oblivious. I’d go and see everything (all the movies were sub-titled in both English and Chinese, as a matter of course), including things like comedies and romances, because I was just fascinated by Chinese movie-culture, and most of the time I’d be the only European in the audience. But I made a point of always smiling and saying hello, and eventually I got to know a young kid who sold tickets in the club his father ran (his mother was a fan-tan dealer in an illegal Gerrard Street gambling joint, which should have given me a tip-off about the Triad connection), who started giving me posters and lobby cards (which I still have), and when he grew up a bit and became a projectionist for another club, he used to let me in free as well. I also got to know Roy McAree, who was the English distributor for the Bruce Lee movies and other output from the Golden Harvest studio, and as I was an avid reader of Chinese movie magazines, I managed to set myself up as a somewhat knowledgeable unofficial consultant, helping with publicity. I didn’t get anything out of this apart from the odd perk, but eventually knowing Roy led to a brief involvement with writing movie scripts.

Another way all this changed things for me was that it provided a replacement for my interest in comics. As I said, when I went freelance I basically stopped reading other people’s comics because I wanted to develop my own style, but there were other reasons as well. By then the major creative explosion of the 1960s had virtually blown itself out, and besides, while the costumed superhero may have seemed great when I was 15, by the time I was 23 they were starting to look unutterably stupid and unappealing. Thankfully, with the exception of a couple of short text stories for a British Superman and Batman Annual and some Hulk stories for Marvel UK (if the Hulk can be considered a costumed hero), I’ve pretty much been able to avoid writing in the genre throughout my career. That’s also been one of the reasons why I’ve been largely reluctant to write for the USA, as I just didn’t want to go to Marvel or DC where I’d have to write that sort of stuff. As an aside, there’s a considerable difference between the American superhero and the Chinese martial hero, even if the latter, with his ability to leap in the air, paralyse with a touch, and so on, might seem to be similar. The American hero usually gets his powers by accident (spider-bite, exposure to radiation, etc.); the Chinese hero gains his by learning techniques and spending years in hard practice. One is naked wish-fulfilment (‘maybe that sort of accident might happen to me’), the other is about hard work. I think that says quite a lot about the respective national psyches.

But the most important way was that I simply wanted to learn more about the Chinese culture reflected in the movies, firstly so that I could understand them better (for one thing, all the adverts for the movies were in Chinese, so learning the Chinese numerals became an absolute necessity for finding out when they were showing!) and then simply for its own sake. I began to read voraciously, particularly on Chinese history, literature and philosophy, and once you start researching those areas, you can’t avoid running into the classic I Ching or Book of Changes, which led to another entire strand of interest, research and writing.

So essentially I’d become a complete sinophile. I loved the culture and history, I developed a great sympathy for the philosophy of Daoism, and all this started to influence my comic-strip work as well, both in that I started including some of this stuff as subject-matter, and also in the fast-pacing of my stories. I occasionally get to glance at the odd contemporary comic, and they always strike me as absurdly slow. Writers these days seem to be spending 20 or more pages on something that I would probably have got into eight, quite comfortably.

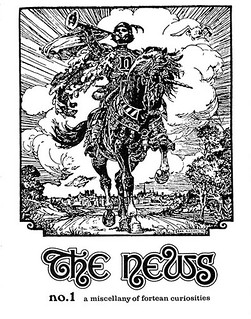

SM: Obviously, all the credit for starting this goes to Bob Rickard, who’s remained one of my two closest friends since we first met in 1968. By the early 1970s he’d become the British agent for the International Fortean Organisation, begun by the Willis brothers in the USA to continue the work of author Charles Fort (1874-1932), who specialised in strange phenomena, and was taking subscriptions for their INFO Journal. He then decided he wanted to do his own journal, which first appeared in November 1973 under the title of The News, which eventually changed to Fortean Times with issue 16 (June 1976). It was a purely amateur affair to start with, the first issue having a print-run of 100, black-and-white, the text composed on a typewriter and the whole thing run off at the local copy-shop. In effect it was a fanzine for strange phenomena, but with pretensions. Bob obviously told me about his plans, and that a lot of the material would derive from news-clippings sent in by readers. So I immediately became an enthusiastic ‘clipster’, and remain so to this day. I also started writing up some of the clipping sections, contributing articles, doing some of the typing, helping with mailing the issues out (in those days we wrote all the envelopes by hand), and for a while was honoured with the title of assistant editor (and later ‘contributing editor’). Unsurprisingly, I did a regular column for a while about Oriental phenomena.

For a while, shortly before it closed down, we began meeting on Tuesday afternoons at DTWAGE, to sort clippings and discuss projects, which I managed to arrange because of my friendship with Derek Stokes. It’s surprising how many strands of my life and interests tend to interweave like this. Gradually the magazine became more professional in appearance and other people joined the ‘staff’, particularly Paul Sieveking, who became Bob’s partner when the journal eventually achieved news-stand publication with John Brown Publishing. And shortly after, in the early 1990s, as the amount of product we were producing increased, I became a contracted writer-editor for FT, with a salary, though I still worked from home.

I’m still associated with the magazine, 40 years on and over 300 issues later, contributing occasional articles and book reviews, and meeting up with Bob, Paul and a small cabal of helpers every few weeks, where we archive the clippings we receive from readers, have lunch and generally keep up to date. With my life very much split between the fictional and the factual, FT has been a major strand in the latter half.

PÓM: Did you sell any stories to non-comics markets at this time? Any of the SF magazines in the UK or US?

SM: Not fiction. My attempts to sell to SF magazines were only around 1965/1966. And after that I just didn’t try to sell stories ‘on spec’ … at least not until I was trying to interest various literary agents in Somnium and a couple of other novel projects, in 2006. Apart from that, I was always working on commission. That may have entailed submitting an outline first, but I was never sending in finished work without knowing it would be wanted … which is what I would have had to do with SF magazines.

Rooting through a filing cabinet drawer to find that copy of Game, I came across another non-mainstream comic item, published in a British underground published by Cozmic Comics in August 1973, called View from the Void. The story was called The Void and drawn by Trev Goring, with lettering by Dave Gibbons. I’ve no idea if we ever got paid for it.

To be continued…

Heidi, I’m surprised you haven’t covered Alan Moore’s call to boycott the Hercules film. Not that you have to hang on everything the hairy bard says (and I’m sure you’re slammed getting ready for ComiCon), but given the reported treatment of Steve Moore by the folks who basically ripped off his work, it seems like The Beat’s natural …uh… beat.

As the whole thing seems to be an ongoing situation, personally I wanted to wait for further developments. I believe the film company / comic company involved are going to make a statement, so perhaps that would be the time to comment, rather than in the heat of the moment, as it were. Obviously, only my own opinion, rather than speaking on behalf of either Heidi & The Beat, or Alan and the Moores, either.

Thanks for this – fascinating stuff.

Throughout the 60s a lot still did. The outer suburban grammar school I went to was one of many where masters still wore gowns. ‘Jennings’ stories didn’t seem in any way anachronistic.

Still miss that, although I no longer have the disposable income. The not being recognized bit is familiar. No matter how long I’d been buying stuff there, regularly one of them would approach me as I looked at the rare stuff at the back and gently point out that these were collectors items.

Interesting about the Obscene Publications Squad bust. There was a London wide crackdown in the early 70s. (This was before the Customs & Excise problems people like Knockabout had). Lot of stuff after that you could only get outside London or by mail order.

Se é isso que você busca, neste texto vai encontrar informações valiosas para alcançar corpo ideal e também algumas dicas

para emagrecer rápido e como perder barriga.

Você, com a mão fechada, vai precisar agarrar firmemente

pinto pela base até sentir alguma pressão, mas cuidado para não

sentir dor.

Pendant les quatre jours, vous pouvez perdre du poids rapidement, à hauteur de 3 à 4 kg.

Ensuite, vous continuez de faire ce régime une fois

par semaine pour stabiliser votre IMC sur le long terme.

Hmm it seems like your website ate my first comment (it

was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say,

I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I as well am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to the whole thing.

Do you have any tips for beginner blog writers? I’d really appreciate it.

Comments are closed.