The werewolf is perhaps the hardest classic monster to get a good movie out of. Those who’ve tried their hand at it have found more success in sticking to practical effects over CGI. For a werewolf to inspire terror, it has to look like something that’s inescapably violent, primal, and real. CGI just doesn’t capture that. We have John Landis’s An American Werewolf in London (1981) to thank for that. Not only did special effects legend Rick Baker produce one of the best werewolf designs ever here, he also gave us the best werewolf transformation sequence to boot. Rob Bottin did the same for The Howling, producing menacing, hungry, and ultraviolent lycanthropes that cemented the movie’s place in werewolf cinema.

It’s 2025 and we have another attempt at creating a werewolf for the ages in the form of Wolf Man, helmed by Saw co–creator and director of the 2020 The Invisible Man Leigh Whannell. While things fare well on the technical side, most notably in the practical effects and sound design departments, the movie is in desperate search of a story that can give it the character work it deserves. It’s a case of style over substance, but one that results in a refreshingly different kind of werewolf.

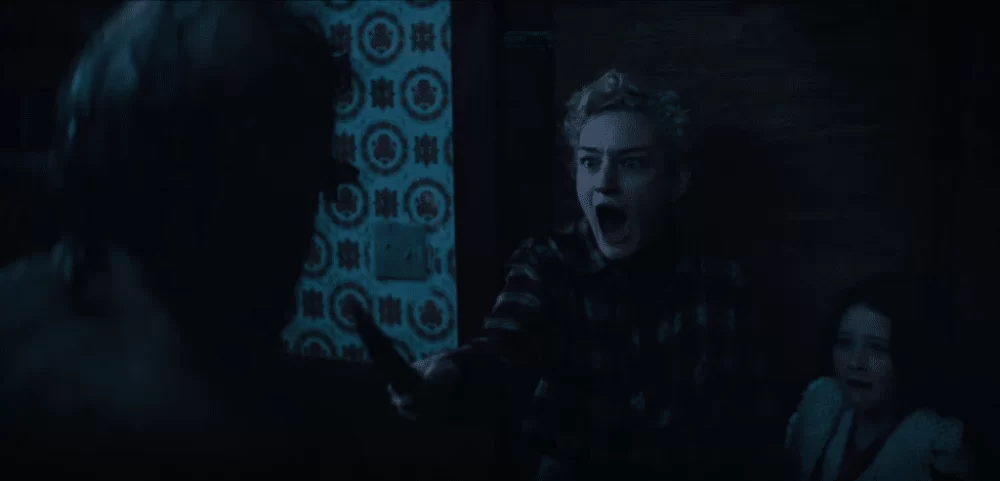

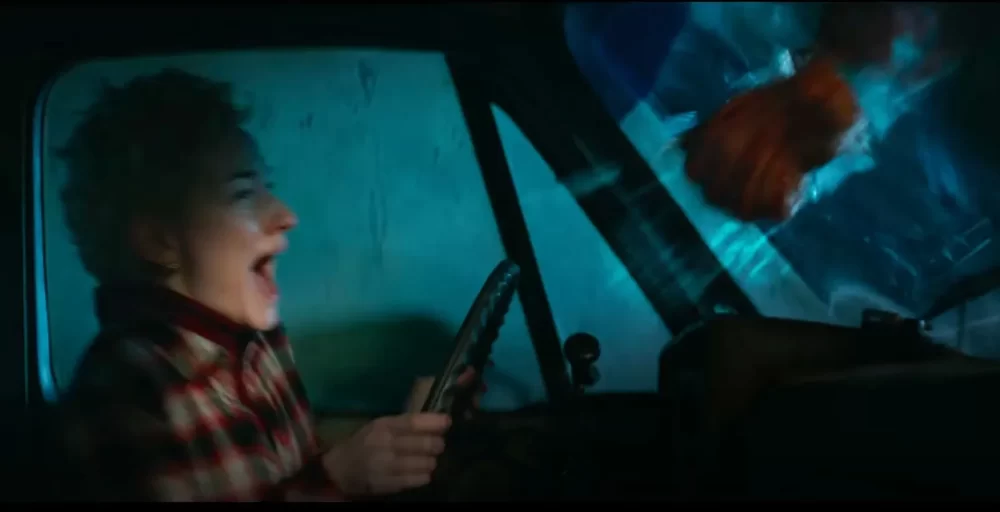

Wolf Man follows Blake Lovell (Christopher Abbott), a man who was raised by an overbearing father that dished out a lot of emotional hurt when he was a kid. He learns that his father has been declared dead and so decides to take his wife (Julia Garner) and daughter (Matilda Firth) to the middle of nowhere Oregon to clean up the old man’s house. The dad was a survivalist/Doomsday prepper that believed there was an infected man loose in the woods, a man that had become a monster. Blake puts a lot on this trip as it gives him a chance to work on his marriage. It all changes when the truck they’re driving in gets into an accident and a werewolf slashes Blake’s arm.

Unfortunately for the movie, this summary is basically the extent of the story’s reach. There are multiple avenues director Whannell (along with co-writer Corbett Tuck) could’ve taken to arrive at stronger meanings and metaphors for a more well-rounded character-driven experience, but each of these is ever only halfway travelled.

In one corner you have Blake’s fears of being consumed by the sins of the father, an idea that’s been a staple in werewolf cinema since Universal’s 1941 classic The Wolf Man. Blake has instances of rage that threaten to make his daughter the recipient of the same treatment he suffered as a child. Those instances, though, are too infrequent to make much of an impact. In fact, the movie doesn’t commit to whether Blake is emotionally abusive or not. He’s just a bit intense with his kid, a symptom of his overprotective personality.

In another corner lies the dangers of fractured parenting and how it can force sons and daughters to choose favorites. The daughter clearly prefers her father over her mother, which makes Blake’s transformation more dangerous as it falls to the least favored parent to keep the family together. Sadly, the same thing that happened to the ‘sins of the father’ angle repeats itself here. The scenes that could build this idea up are simply undercooked and lacking in sufficient emotion to make a dent in the story.

And just when you thought all hope was lost, in comes the saving grace. Turns out, the highly dysfunctional and half-baked story at the heart of Wolf Man is superbly shot and realized. Much of this is owed to the practical effects (courtesy of prosthetics designer Arjen Tuiten), and the inventive ways Whannell settled on to set his wolf apart. First off, Blake’s transformation is a drawn-out affair that is painful to look at. The slow pace puts the tragedy of the situation at the forefront by showing how each new stage towards lycanthropy pushes Blake further away from his wife and daughter.

This is further amplified by the manner in which the transformation shifts and alters Blake’s perception of the world around him. The scenes where we get to appreciate this rely on smooth panning shots that come with a change in the colors surrounding the environment and those occupying space in it, distorting the visual dimensions of everything Blake sees as the camera moves from one side to the other.

Exceptional sound design rounds out the werewolf transformation, pulling the audience deeper into the transformation. You really get to appreciate how Blake’s senses become sharper and deadlier as the creature takes over. You hear bones cracking to better support wolf form. Then you hear low growls announcing the imminent arrival of the thing writhing within Blake. It helps to build up one of the best howls ever captured in film. It’s a deep guttural sound that grows rather forcefully into a signal of something utterly terrifying. It’s a standard-setting howl, and I hope future werewolves take it upon themselves to match or surpass its distinctive tone.

Wolf Man is a frustratingly imperfect movie. A more refined script (something that Whannel has more than proven capable of pulling off before) would’ve truly elevated this werewolf movie to exceptional status. As it stands, it’s an achievement in monster creation and experimentation, but not in storytelling. The transformation, the creature, and the sights and sounds they create are the stars of the movie. It’s a shame the script couldn’t keep up with the monster.